Mom’s book, our bubbly

July 28, 2023. Los Angeles.

Then:

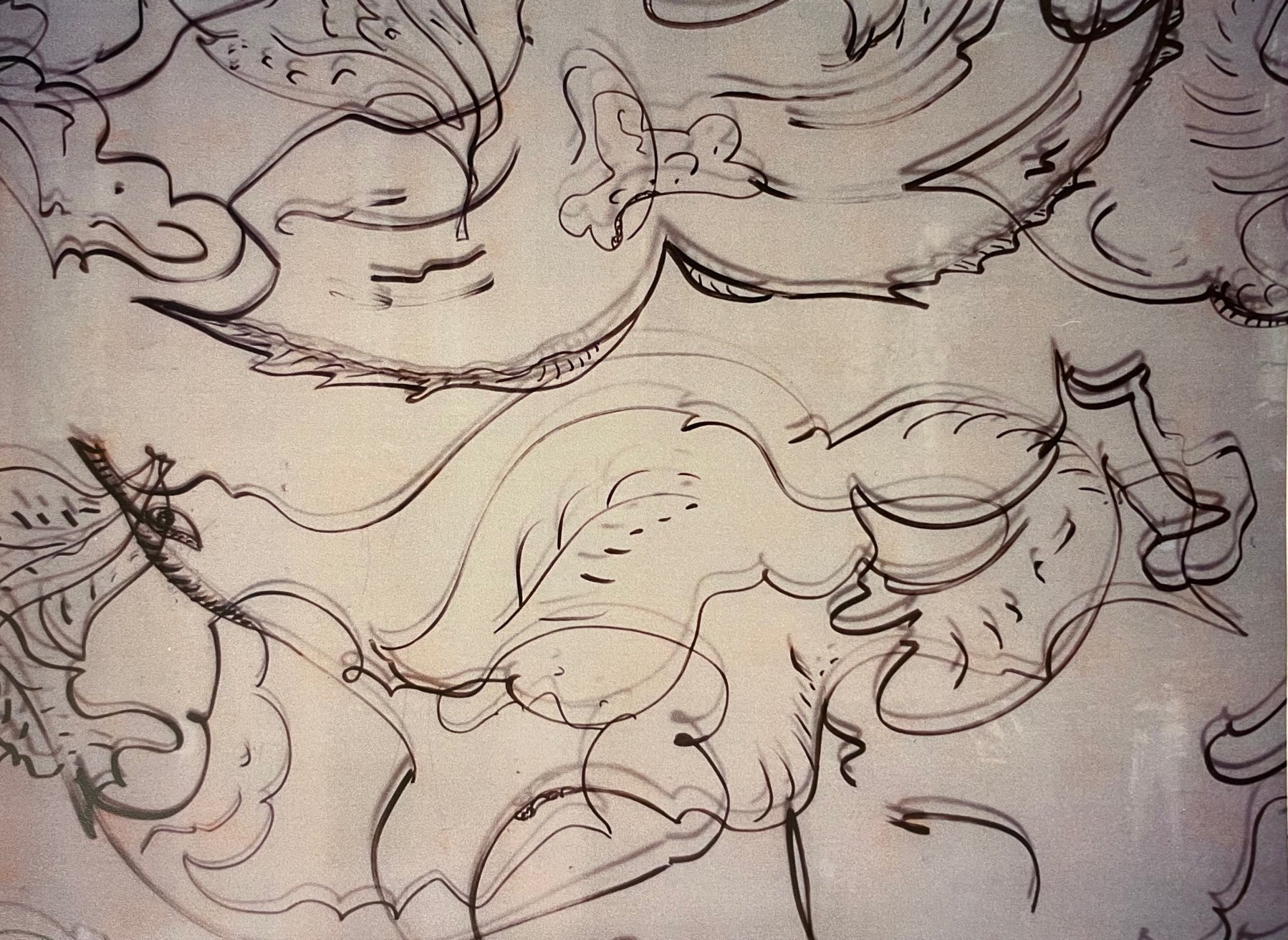

After the Liberty Series I went back to painting to classical music, my whimsical lines danced across white canvas. For a while my art caught the attention of people from one major ballet company but watching me living on the verge of poverty made them uncomfortable.

I moved my studio to a large white building near Downtown Houston. I did a few sets for a small ballet company. I loved creating 3D effects with my backdrops. I tried to approach choreographers with my visions but my time for doing this was limited.

~

Now:

She has a craving for “blue bubbly”, which is what we’re calling the sparkling water that comes in some fancy blue bottle, available at a specific grocery store in her neighborhood. And maybe some of that imitation crab meat they sell too. So I race to the car; taking care of someone who is dying, it seems, may resemble taking care of a someone who is pregnant. When there’s a craving, a want — particularly a food — you don’t argue, you go. So I go.

~

Then:

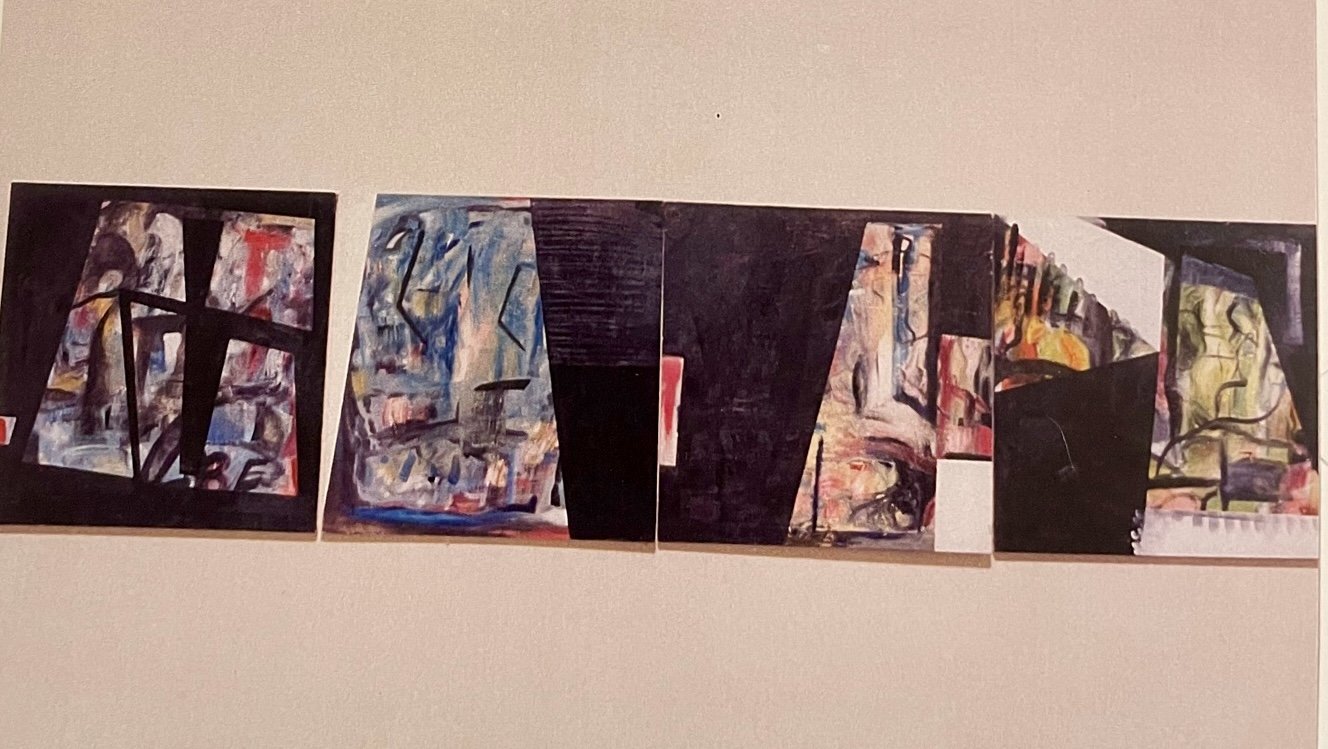

In my large white studio, during two hot Houston summers, I fought battles with my canvas. What is my essence? I was wondering. Suddenly I abandoned line and explored light in my hard edge series. I felt that I conquered darkness after all. But I was almost broke.

~

Now:

She is me.

This is the thought that comes to mind when I see a woman standing on the median grass beside the turn lane I’m in, in the car, waiting for the traffic light to turn green. The woman, she’s maybe in her thirties, Latina, and she has some long-stem roses in her hand and a sign around her neck. The sign reads: Single mother of 3. Anything will help. She’s selling the roses. It’s 94 degrees and not yet 11 a.m. — this according to my car dashboard.

She is her. She is me.

I go to my pockets, my glove compartment, searching for money. The woman’s eyes are looking up and down our row of cars, searching for signs of interest within any of the cars. Surely she gets more looks away than looks returned. But now she’s seeing me fumbling around, and lowering my window. She moves towards my car. “How much?” I call out. She sort of shrugs, says something I hear exactly because the light’s turned green now and the cars in front of me are moving. A look in the rear-view shows several cars behind me, waiting for me now. Probably cursing me. “I’ll come back around, OK?” I say, and step on the gas so the people behind won’t miss their chance to turn left before another red light.

~

Then:

In the fall (or was it winter?) in a cold warehouse I painted my last backdrop, and made a last attempt to get into the business of stage design. It didn’t work.

~

Now:

The left turn, then a U-turn where probably I’m not even supposed to, then a right to get back onto Sepulveda where she was, and then another U to get back to that specific turn lane.

She is me.

~

Then and now:

Mom’s book, it’s approaching here in its narrative a point of separation. Of fragments. Separation and fragments that were painful to me then, to us, yet I look at those photographs now of her backdrops, and that ballet dancer, and it calls to mind some of the good times we had just before our lives split into those separate fragments: when I’d watch Mom for hours just working on those backdrops, creating a looking-window through her fingers as she always did during pauses, and asking me if I was hungry. Or, how the dipping of her brush into those stage-design waters may not have a yielded the ‘break’ we were always hoping for, but I do remember how it led to random treats for us here and there, crumbs from the good life, like tickets to performances at the Houston Ballet. Those nights were, for us, something we always giggled through: first, the theater was downtown, so it was a healthy drive for us in the worst car Dad could have ever left us in the divorce, that Volkswagen Dasher that trembled more than it drove. And how that Volkswagen always looked so out of place, as we did, when we arrived at the theater parking and then went inside among the rich, the smashingly dressed. I remember how those sweet-smelling people sipped their golden bubbly during intermission while Mom and I just went to pee.

Or how the real theater, for us, was always after the show, back in that underground parking garage when we had to get out. I remember how the cars would crawl and stand, stop and start, and how our Volkswagen trembled among shiny black things, smoother things, and then the real nightmare: Mom always fighting with the manual transmission once we’d hit the upward slope leading us to the street-level exit. Our awful ugly car always seemed horribly misplaced to begin with, but when we’d reach that upward slope: terror. Because the car had a tendency to putter out and need kicking even on flat ground sometimes, but on an uphill climb it fought especially against, and Mom also had problems with shifting the gears and working the clutch and gas just so to prevent the car from rolling backwards too much out of the stops. And so we’d go backwards. Mom would slam on the break. Try to shift out again, and again we’d go backwards. And in that parking garage the fancy cars behind us would often grow impatient or fearful, scared of being scratched. There would be honks or sometimes a domino effect of people then reversing behind us to give Mom more room, but then one night the cars behind us just weren’t moving back at all and Mom was getting too close to the bumper of the fancy thing behind us, and she began to panic. I began to panic too.

I remember then the man in the car behind us then getting out of his car and approaching ours. Mom may have been crying by this point. My own heart was racing. And when the man recognized the situation, perhaps softening when he heard her apologizing in her adorable European accent which always stood out so uniquely in Texas, he offered to help, to swap places with her to get our car up the slope for us. Mom got out, he got in. This man was in a tuxedo. His shoes were even shinier than his car. He smelled good. In other words, he was an alien. But he worked the shifter just so and got our car up the slope, and Mom thanked him and got back inside, and then all of us were on our way — the fancies in front and behind us heading back to their homes in neighborhoods with names like River Oaks; us in our puttering Dasher, heading back to our little apartment.

Eventually the money just ran out. Mom’s various survival jobs — and they were odd, she was even a security guard at an office building at one point — wouldn’t hold, or pay enough. Her big break in the art world wouldn’t come. Then a temporary job opportunity was offered to her in California. Lacking the ability or funds to take us, she went there to go make some money and I moved into the family home of a classmate and friend.

I put my things in storage and headed for California where a summer job was waiting for me. I could no longer survive in Houston. My older son was in college and my younger one stayed with my friend finishing high school. Thanks to Jenny Malone, my friend, whose boys went to the same school and who took my son into her house I could continue with my life. I packed my van with canvas and things and drove to California. I couldn’t believe how beautiful Orange County was. I drove to work looking at plants I had never seen before, all in full bloom. Trees covered with white, bushes with unexpected colors, like purple. Fresh air. If ever there was any darkness in my painting I knew that it was going to change. A painting with a dark face had a background - all pastel. On the forehead I put a perfume bottle — a symbol of life that now has the element of pleasure.

~

I stop, say I have six bucks on me. What would that get me? What’s fair? The woman, standing there in the awful heat, hands me a pink rose and a red rose with question marks in her eyes. I say Perfect, thank you, and she says God bless you. I roll forward, but the light is still red and so I keep my eyes on her, now in the side-view mirror of my car as she stands there, looking behind the glass of other windshields now, that sign around her neck, just looking to sell a few more flowers, make a few more dollars for her and her children. Probably she’s an immigrant, like Mom. Surely she has dreams, like Mom. Images on the mind. Even perfume. But for now she’s just surviving, the roses in her hand for the others, for now.

What’s the difference between her and Mom? Between her and me? Between us and that ballerina in front of Mom’s backdrop? Hell, even between us and the cats here, the cats Mom rescued from the street and gave new life to, these cats who spend their days now hoping just for that next cuddle or cup of tuna?

What’s the difference between any of us?

Really nothing. It’s the body we’re born into. The time. Maybe then a spot of luck, a chance. It’s where we’re born and into what. It’s who looks back. In the end, we’re all just here surviving, dreaming, fighting, breathing for as long as we can. We’re in our lines, at our red lights, waiting for our green. Our break. For the ground beneath us to level.

She is her. She is me.

I set the two roses on the passenger’s seat of my car, and make the left, towards the store for Mom’s water, our blue bubbly.

~

Later on I almost abandoned black. After 8 months I was heading back to Texas. I saw my son, but my car broke down and I found myself in a bad situation again. It was better for me to go back to California, this time by train.

I worked survival jobs.

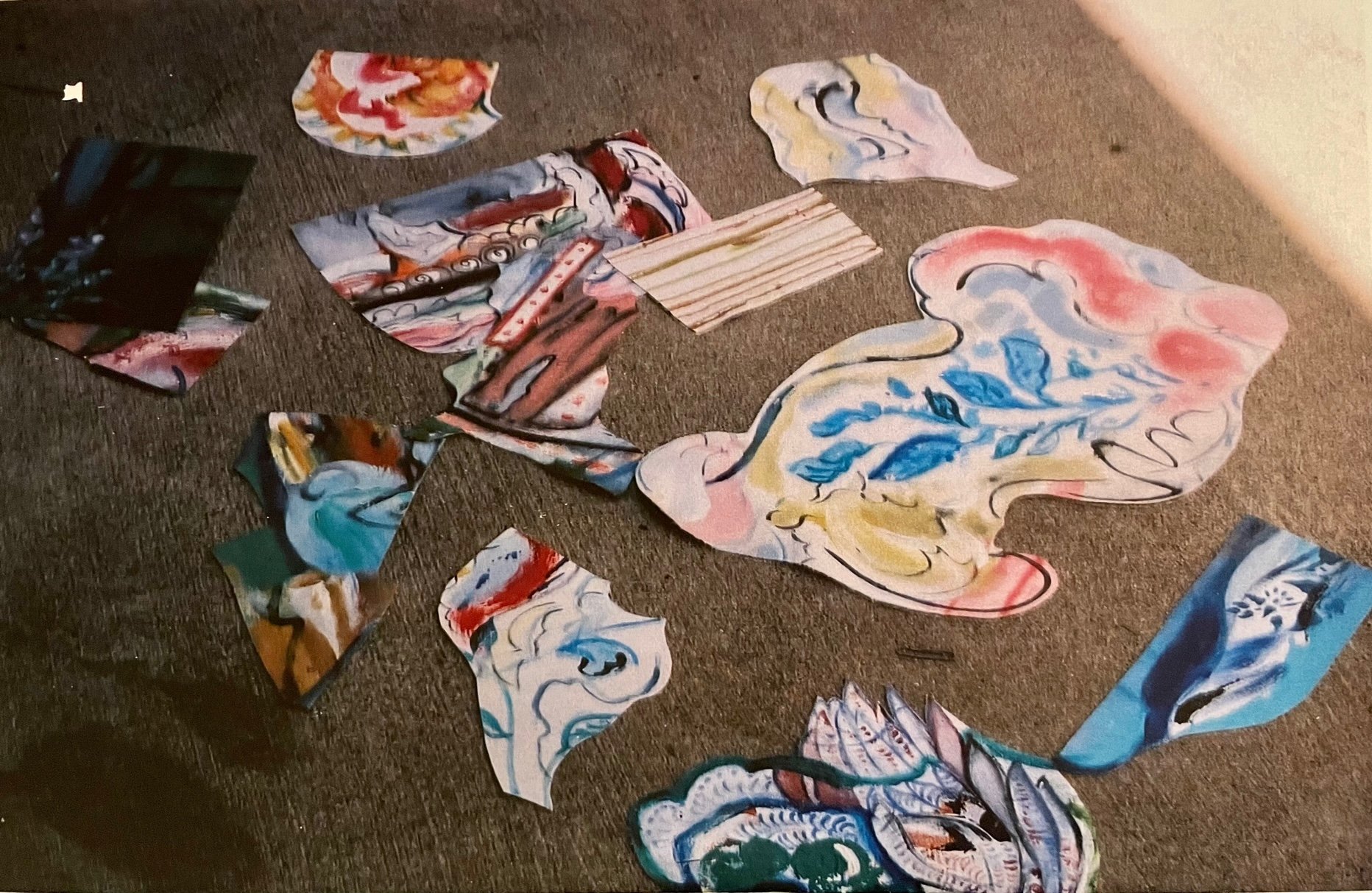

The canvas I had with me seemed to be too busy so I was taking scissors, cutting it into pieces hoping that these pieces would make great collages someday. My life and my canvas were “in pieces”. Some day this will fall into place — I thought. Just have to wait for the dust to settle.

~