Still life

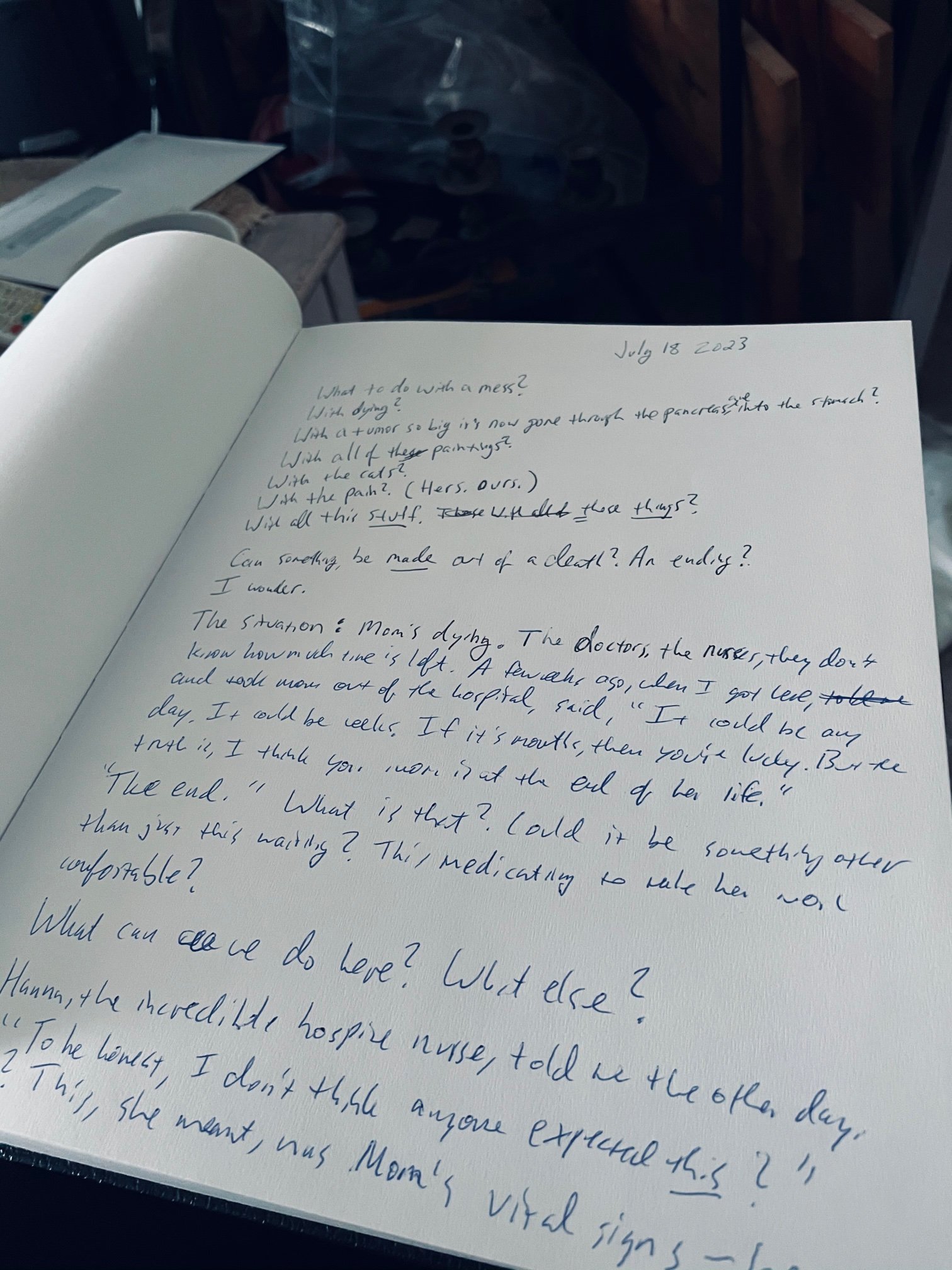

July 18, 2023. Los Angeles.

What to do with a mess?

With dying?

With a tumor so big it’s now through her pancreas and into the stomach?

With all of the paintings?

With the cats?

With the pain? (Hers. Ours.)

With all this stuff. These things.

Can something be made out of all of this? Out of a death? An ending?

I wonder.

The situation: Mom is dying. The doctors, the nurses, they don’t know how much time we have. A month ago, when I arrived here and got her out of the hospital, took her home, the doctor said, “Difficult to say, really. It could be weeks. If it’s months, then you’re lucky. But the truth is, I think your Mom is at the end of her life here. And every day is a gift.”

The end, he said. But what is that? Could the end be something other than just an end? Or this waiting?

What can we do here? What else?

Hannah, the incredible hospice nurse, told me the other day when she came for a visit and Mom left the room for a moment to go get a gift she wanted to give to Hannah’s daughter, a book, “I’m so happy you’re getting to spend time with your Mom.” And I whispered back that I couldn’t believe it was going as well as it’s gone, that Mom is really hanging tough here. Hannah nodded. She said, “To be honest, I don’t think anyone expected this.”

This, she meant, was Mom’s vital signs — her heart rate, her blood pressure, her oxygen level — all great. Great still. The oxygen machine they delivered at the end of Week 1? It still sits, unplugged, unused, among all these other things. A walker, too, remains folded up. “Whatever you’re doing, just keep doing it,” Hannah told me.

What we’ve been doing:

Soups. Soups from restaurants, from the grocery store. Soups with things like spinach or beets we add into them to combat the anemia caused by the bleeding inside, which we wait for again; but when it happens again, no more transfusions.

Films. Her favorites. Whatever she wants. We’ve watched Brooklyn so many times we’re now reciting all of the lines before the actors say them. And laughing.

Cats. Mom’s got four of them, and we’re taking care of them like kings and queens, while these little kings and little queens look on and wonder (or know?) what’s going on. There’s Snowy, the fat one. And Fillow (Feel-O), the furry one, the lover: Fillow the greatest lover of my mom’s life really, a furry Russian Blue who’s spent his own life worshipping hers, following her, worrying about her, hugging her (it’s true, he hugs); but now he has a bump on his head, a mass of some kind also, maybe a tumor, maybe a desire to go “out” with Mom in one final, grand romantic gesture. That’s what Mom thinks, anyway. But still we’re doing all we can to treat him, too: the eye drops, the oral steroids, and here lately the shaving of his thick mottled hair down to make him more comfortable in this awful summer heat. And it’s working! His left eye, so much better now, more open all the time, not watery as before, less tears. His mood? It’s gone to day from night; no more hiding behind the paintings and being alone back there. Now he’s out in front of them, he’s part of this canvas again, purring again, a lion again. … The other cats are Munka (Moon-ka), the little flower pot (she mainly sits in the window, and thinks); and upstairs, in her own room or often in the closet there, hiding as usual, is the feral Swifty. Swifty who my mom rescued from the car park many years ago but still she refuses to let Mom or anyone else reach for her, touch her.

Yes every day: the feeding of these felines, and the cleaning of their litter boxes, and the doing whatever else we can to make them happy. Because they are therapy for us too.

Cleaning. This mess! Yes, Mom is what some might call a hoarder. She collects. Doesn’t throw anything away. And one can’t really blame her for this: she grew up in a communist country, valuing every possible thing she and her family could attain. So now she values every possible thing even a little too much maybe, or maybe it’s the rest of us with the problem, not her. I don’t know. But there have been negotiations and some things taken, day by day. Things cleared to make more room, things donated to the Salvation Army or Goodwill, or to the neighbor who sends clothes once per month to the needy in Mexico. Every day these negotiations, these little tasks.

Talking. We talk about everything, really. Even It. The thing we’re waiting on. And she’s OK with it, the dying. She’s unafraid, really. Because Mom is a Believer with a capital B, and I’m so happy she is. Because it means, for her, that even this has a purpose, a point. It’s by design. And Mom herself has always been a designer — just look around this place, at the paintings all over. Mom is a million things, but she’s an artist at her center.

So: can death make some new design?

Can we create something out of this — maybe together?

She handed me a book today, something she wrote almost twenty years ago now. An explanation of herself, of her art. It was her attempted answer to when she would try to sell herself and her work to galleries, and the people there would eye her resumé rather than her art, and ask: "… But what were you doing during this period? There’s a gap here…” They always wanted more. They always do. More exhibitions, more successes. People want any excuse to pass on another person, to say no. So she got a bit fed up and created this kind of booklet explaining herself, her life, her art, her ideas — and her gaps. She printed this story out from her computer. The book has grammatical mistakes here and there, owing to Mom being an immigrant and English being her second language. The book, and its language, is imperfect. But it’s beautiful. It’s her. And I’m so happy she made it, even if it led to nothing much with those gallery types. I’m just so happy to have it now and forever, this piece of my mom on these pieces of paper. And I’m wondering: can we do something with it still?

I’m thinking.

“My problem,” Mom told me very late one recent night, when the lights in her room were dim and she was nearing sleep, “… my problem was that I was always thinking about other people when I was painting. About whom I could sell it to. Who would want it. My art was never just for myself. And that was my problem.” She looked up at one of her rare still-lifes, a simple painting up on her bedroom wall now, just some flowers in a vase. “Maybe I should have done more of that. Just painted flowers. That could have made me happy.”

Thinking.

She’s upstairs now, sleeping. It’s 1 a.m. I’m down here with three of the four cats now around me: Fillow at my foot, Snowy on the floor, and Munka over in the window as usual, thinking also. And I’m just trying to make something of this thinking. And setting these words down to the first pages of this unused sketchbook we found among all of the things. And I’m thinking: let’s make something here, out of all this. Let’s at least try.

I don’t know what.

And I don’t know for whom. Maybe just for us. For Mom. For me. For my grandmother back in Poland. My brother. For my mom’s brother and his family up in Oakland. For anyone who loves her but can’t be with her. I don’t know, just something for us maybe. And for the moment.

That’s the idea, anyway. The thinking — tonight.

What will come tomorrow of this mess, this thinking, this dying, I’m not sure. But I’m just going to start putting some of this down. The snapshots of these days. In words. In some pictures, maybe. These memories, these moments. Maybe I’ll take my mother’s little book and fold it in to all of this, and we can make it into something.

Mom’s art? Her paintings? The stacks of them here beside me on this downstairs bed, and the stacks of them everywhere else in this place? The canvases rolled up and stuffed also into the closets? Almost all of them are abstract, not still-life. They’re paintings where one must find the painting for themselves, find what it is that’s in there, the meaning, the feeling. And maybe with this, this dying and this experience of helping her, and this thinking — maybe it’s the same. Something abstract that’s here, and into it we should go, go looking.

Let’s use the mess. Roll around in it. See if we can see something. Maybe create an even bigger mess.

Let’s play.

The point is: let’s make something. With no idea yet, of what.