A winter’s touch

As time slips on by, as it seems to move along and away even faster now with these last two years robbing us of contact, of meeting, of chance encounters and little smiles now hidden beneath our masks — of magic, really — I find myself steering off into those spaces where magic still exists, where the world can seem more sane, more free, more filled with the very thing now lacking: touch. Touch with other humans, other places, other thinking; simply, with some other. I’m talking here about art, and especially about books. And as the calendar flips over and onward, and the date of January 7 now arrives, I can’t help but to think also of the one winter when a similar angst and pursuit — the pursuit of some story, some else — led eventually to a chance encounter with not just a new story but also that story’s author. He was someone who, until then, I had not even known existed. His name was Konwicki.

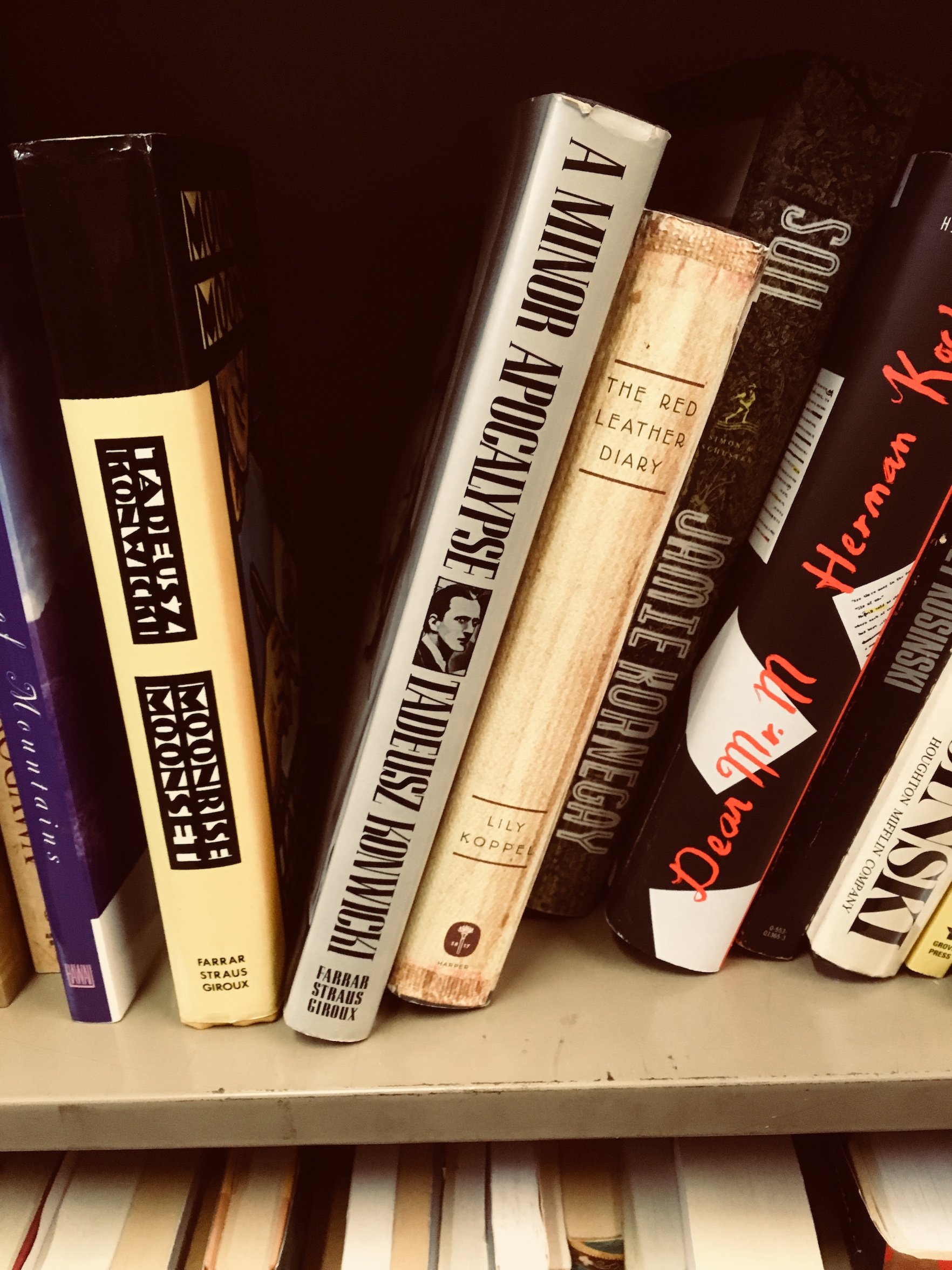

And Konwicki was the name I first saw on the spine of a little red book in the English section of a Warsaw bookstore. This was on an avenue called Nowy Świat, which means New World. I was in Poland then just for the holidays, visiting from New York, visiting my grandmother. And there again, I was missing something. And so it happened that I found myself moving through the city, moving from bookstore to bookstore and asking in my clumsy Polish whether there were any books in English, and looking. For what exactly? Often we do not know this until we find it. Until some sentence, some title — a cover maybe, or just an energy — speaks to us in some way. When I saw the book up there on that shelf, with the name Tadeusz Konwicki and the title The Polish Complex, and an eye — yes there was a man’s eye on the spine also, now eyeing me back — I reached for it. I opened the book. I read.

I was standing in line in front of a state-owned jewelry store. I was twenty-third in line. In a short while the chimes of Warsaw would announce that it was eleven o’clock in the morning. Then the locks on the great glass and metal doors would rattle open and we, the sneezing and sniffling customers, would invade the store’s elegant interior — though, of course, ours would be a well-disciplined invasion, each person keeping the place staked out during the long wait in line.

Something was in there. As I read on, in those initial pages, something was in there in that line, in the language, in the feel of the place and people there. It was an energy, a longing.

What are you waiting for, a miracle or something?”

There was a stone plaque on the wall of the building commemorating the spot where, during the war, fifty nameless people where shot; below it a paraffin memorial candle in a green jar kept flickering, then flaring back up again.

“Yes, you’re right. I’m waiting for a miracle.”

In those initial pages, a “red snow” was written to have been falling. Outside of the little bookstore where I was then standing, it had begun to rain. Soon I was taking the story with me into that rain. Tucked beneath an arm to keep it dry, I was then taking it with me to cafes, to the tram, to the cinema and of course back to my grandmother’s flat.

This is how it began.

“No co tam? Dlaczego ty śmiejesz?”

In the doorway, then, stood my grandmother. She’d heard me laughing from the other room, and had come to ask what was so amusing.

I held the book up. Babcia, I told her in my broken Polish, this is so interesting…

She drew closer, spotted the name on the cover, stopped. Konwicki? In English? Where did you find this? …

I told her, and asked if Konwicki was well known here, and she said of course he was, and grinned a grin I’ll always remember. She sat down. Said, “Do you want to hear a story?”

The story was: my grandmother had actually known Konwicki but more so his wife, long ago. This was after the war, back when they were all just starting out as artists in a ruined city. My grandmother and Danuta Konwicka had studied together at the art academy and were then illustrating for some of the same publications: Świerszczyk, the children’s magazine, or Nowa Kultura, a literary weekly.

Soon my grandmother was pulling these publications from a cabinet, and scrapbooks too, and wiping away the dust and smoothing out some long-ago pages. On one of them, Danuta and my grandmother’s works were even side by side, although my grandmother’s first name there was for some reason errantly credited as Jadwiga, not Maria.

Babcia went on to tell me of Warsaw then, of how it was — for everyday people, and for young artists such as themselves. Tadeusz Konwicki, she explained, would end up taking a road more bravely traveled: in his work, his writing, he lampooned the communist system in which they lived, and thus his stories were often censored or entirely disallowed. Instead, here they were printed illegally by the underground press and passed around more discreetly.

And there was something else. “Do you want to know the last time I saw him? Konwicki?” Here she smiled again. Shook her head again. She told me that some years ago now, she’d last seen Konwicki sitting at his favorite table, in his favorite cafe — for years, she explained, Konwicki was known for visiting the same place, that same table, at the same hour of every day — and on that particular day she saw him there and stopped, and said hello, and asked him also to please pass on a greeting to Danuta.

Konwicki said nothing, only stared up at her in response. My grandmother figured he was just trying to place her within his memory; after all, by then it had been many years, and she and Danuta had fallen out of touch. “It’s OK, she’ll remember,” my grandmother added. “Just tell her Mucha said hello.” Mucha, or Fly, was my grandmother’s nickname.

Still Konwicki said nothing, only stared. So my grandmother retreated, went home. She told her husband of the strange thing that had just happened, a thing she wouldn’t understand until later, when she opened that day’s newspaper, and saw an article there on the page: Danuta Konwicka, regarded illustrator and wife of the author Tadeusz Konwicki, had just passed away.

“Can you imagine?” my grandmother said. “Of all days, for me to see him there. And to say that.”

Now? Now we were both looking at the red book between us.

“You’ve been to Blikle, right?” she asked. She was speaking of the cafe. “No? Well, you have to see it.” It was Warsaw’s oldest and most important, she said. A part of the city’s cultural fabric. And it was there, just there on Nowy Świat also, the same avenue where I’d found the book.

But surely Konwicki wasn’t still going there, my grandmother said. That was years ago, and by now he was really quite old — “like me.” But still, still we should go one day. And we could always ask.

By the morning on which we traveled there, I’d finished The Polish Complex and had been thoroughly taken by it. At times hilarious and at others heartbreaking, the novel told the story not just of those people in that Christmas line, but of communist Warsaw, of this country and its tragic history, and of the many ways that that history had manifested itself into the personalities of its people. Curiously, even though he’d written the book back in the late 70s, I’d found the people there more closely resembling the Poles I was just then meeting in modern day, in fact more so than any other story I’d read by a Polish writer.

As can happen with a newly discovered voice, I hungered for more of it, and went looking. Returning to the Warsaw streets, again I peered through its various bookstores, but nowhere could I find further translations of Konwicki’s works. I struggled to find him even on the Polish shelves.

Nevertheless, some of those translations were still on their way — failing to find them locally, I’d found and ordered some old and used copies online, from a UK bookseller.

And then we were there. Finally at Blikle, the cafe. And my grandmother was asking a waiter about him, about that old author named Konwicki who used to come around.

“Sure,” the waiter, who was wearing a bowtie, then said. He was looking down at his watch. “He’ll be here in twenty minutes.”

My heart leapt. And sure enough, just when he was supposed to, an old man walked through the door. He was alone. He was fairly small. He hung up his coat and hat on a rack, and sat down at his usual table, which now had a flower placed upon it in a little vase (the waiter had done this, and placed a Reserved sign, just before the old man’s arrival). Konwicki looked past the flower and stared at the door.

Eventually my grandmother got up, went to him, leaned in and whispered. Only later did I find out what she was whispering: that she really didn’t wish to bother, but her grandson was there with her, there visiting from the States, and had just read one of his books, and might he have time to just say hello?

Graciously Konwicki obliged, inviting us both to come have a seat at his table. I approached, and somewhat nervously shook his gentle hand. And eventually I told him. I told him — or at least tried to tell him in my terrible Polish — just how much his story had meant to me. How it had come to me when needed.

And somewhere, somewhere in the midst of that embarrassing mess, my grandmother chimed in also, telling Konwicki that I, too, was a writer. It was then when Tadeusz Konwicki looked up at me in some different way, and he raised his hand up to my shoulder, and for a moment held it there.

What was this? A touch of recognition? Of camaraderie? Perhaps it was merely condolence. Whatever the touch meant, it was one I will forever cherish.

At my grandmother’s urging then, I showed Konwicki his translated book, fetching it from the bag I’d brought, and Konwicki looked upon it as a ghost. “Where did you find this?” he asked, echoing the same surprise I’d heard in my grandmother’s voice. When I told him, he suggested it must have been a donation. After all, he said, people didn’t much read him anymore, even in Polish. But I told him I would be reading him, that I’d ordered whatever else I could find of his translations, and we carried on a bit like that until my grandmother leaned in during a silent moment and mentioned also that she’d long ago known Danuta, his wife.

Here, Konwicki looked up. He became lighter somehow. He said, “You knew Danuta? Fifteen years I’ve been without her. Fifteen years I’ve been alone.”

Then, for some time, I just sat there. I sat at that table and watched as two people floated away. Konwicki and my grandmother, I watched as they traveled back in time, as they spoke of youth, of shared acquaintances, of the almighty then. When a beverage and plate of cookies eventually arrived at Konwicki’s table, my grandmother and I decided to let him be, leave him to enjoy his little meal in peace. He shook my hand once more, and then reached across the table for my grandmother’s, hand and pulled it in closer, and kissed it.

A touch of the old world, there on New World Avenue.

“What kind of miracle are you waiting for?”

“The miracle of understanding. Lately, that’s what I’ve been living for, that’s all that absorbs me.”

In the days that followed, I left a note for Konwicki back at Blikle, thanking him for his words, his generosity, his time. Never mind that the note was written in English, that I didn’t even know if he’d be able to understand it; sometimes a person is simply compelled to put words to paper, no matter what becomes of them.

And such has been the case with me and this story, ever since.

See: eventually I came back to Poland, not merely to visit but to write a book about Konwicki, about my artist grandparents, about Warsaw then and now and ultimately about that curious thing, an invisible thing, which can sometimes happen in the space between a line left on a leaf of paper and a wandering eye: a kind of traveling, a wondering, a seeing. Through generations, through space and time.

And I write this reflection today only because this is the day, the seventh of January, when during that same Warsaw winter Tadeusz Konwicki passed away. This was just a few weeks after we’d sat down with him there at Blikle. And by then I was back in New York, and the news traveled over, and when it did I was left to just shake my head as my grandmother once had, at the wonderment of it all.

But still I could go to him. Such is the added beauty of books, and of the people who leave them: still I could go to him, could hear his textured voice, could feel his hand upon my shoulder and spend a little more time with him and the people he created. After all, I was one of them:

In Moonrise, Moonset, Konwicki’s diary of sorts and the second of his translations I read, I came upon these words across Pages 199 and 200. Actually, I came upon them initially on my last afternoon in Warsaw that same winter, just a few weeks after I’d met him, and nine days before Konwicki would would make his earthly exit. There he wrote:

Anyway, I’ll be taking a break soon, but before I do, I’ll sigh softly about something I think about often: in thirty or forty years will someone reading my writing feel a sudden closeness to a person who lived so long ago, who had his own twisted life, who was almost persistent in his pursuit of something or other, and who in the end achieved nothing? Will that future reader perceive a sort of spiritual and intellectual affinity - if only in the sense of humor - with some man by the name of Konwicki ...?”

Konwicki had written those words thirty-four years earlier, the same year I was born. And I remember reading them that first time, and uncapping my pen, and adding my own ink there in the margin next to his:

Yes, Mr. K, how do you do?

Yes, as the time slips, as it slides yet further away, and as I continue on in this pursuit of something or other; yes on this day I’ll sigh softly too, and think of him, of that Mr. K. About his hand on our shoulder. About the miracle he left.

Story and photos by Jan Gajewski, based upon my work, Old World Avenue.