Babcia Mucha

Not far from the Wisła River in Warsaw, on an avenue called Aleja 3 Maja, or the Avenue of the Third of May, there lives the greatest grandmother in the world. This woman is an artist. Straight away, this is the most important thing to know about her, before even her name. Because art, more than anything, informs who she is. Shape and color, they sustain her. Shape and color through even the more shapeless, colorless times. Shape and Color and Light — yes, these are the better names with which to define her.

Even today, at the age of 91, she will create. Yes today, after she’s eaten breakfast and taken her pills, showered and dressed and put away her bed linens and of course the dishes — Musi byc porzadek, there must be order, she always says — she’ll then head to her workroom on the other side of her apartment. And there, there where the windows are long and the natural light is best, there where the hum of the traffic and the trams of the Poniatowski Bridge just outside will keep her company, yes there is where she’ll take her seat on a hard wooden chair — the one blotched with decades-old paint, and which creaks louder with every year — and she’ll lean over the next leaf of paper, and begin.

What happens next, what will then begin to appear on that stretch of white, will be something messy or something clean but always it will be something that wasn’t there before. For this grandmother, my grandmother, this is breathing. For this woman who always loved to go flying, this is the plane she can still get on, and go.

Her name? It’s Maria. But those who know her best call her Mucha, which in Polish means Fly. So to me she has always been Babcia Mucha, or Grandma Fly. The nickname was given to her by her father when she was little, because she was little and because she couldn’t keep still. Yes even then she would wander, she would drift, she would itch to fly away. And she’s remained that person through it all — through war and through communism; through the loss of a beloved brother much too soon; through the absence of her children and grandchildren, who reside in America; and twenty years ago now, through the loss of her husband, the love of her life, the grandfather after whom I’m named.

My grandfather is the reason why she’ll never replace that creaky chair. It was his gift to her. As was the glass table on which she works. And so: there he is, too, in that workroom every day, supporting her. It used to be that he’d wander in on his breaks from developing his own pictures — he was a photographer, with a dark room on the other side of the apartment — and take little peeks over her shoulder. Sometimes he’d mutter an opinion as to whether he thought she was really on to something, or whether something seemed a bit off. Occasionally he’d say Nie ruszaj tego, don’t touch it, which meant it was perfect as is, pencil down. It was remarkable how often he was right.

Her art form? Once it was a thing called drypoint, a rare, laborious technique involving taking a block of metal and carving into its face, chiseling there a design to be smeared over later with ink, and then pressing that ink-stained slab to paper, creating a print. My grandmother always loved the physicality of drypoint. The steps, the discipline. How it was so peculiar or temperamental, something not so straightforward. A little bit like her, or her country.

These days, she sighs when admitting drypoint is for her no longer feasible, that her hands are just a little too weak. It’s the same sigh she gives when discussing airplanes, and no longer being able to go.

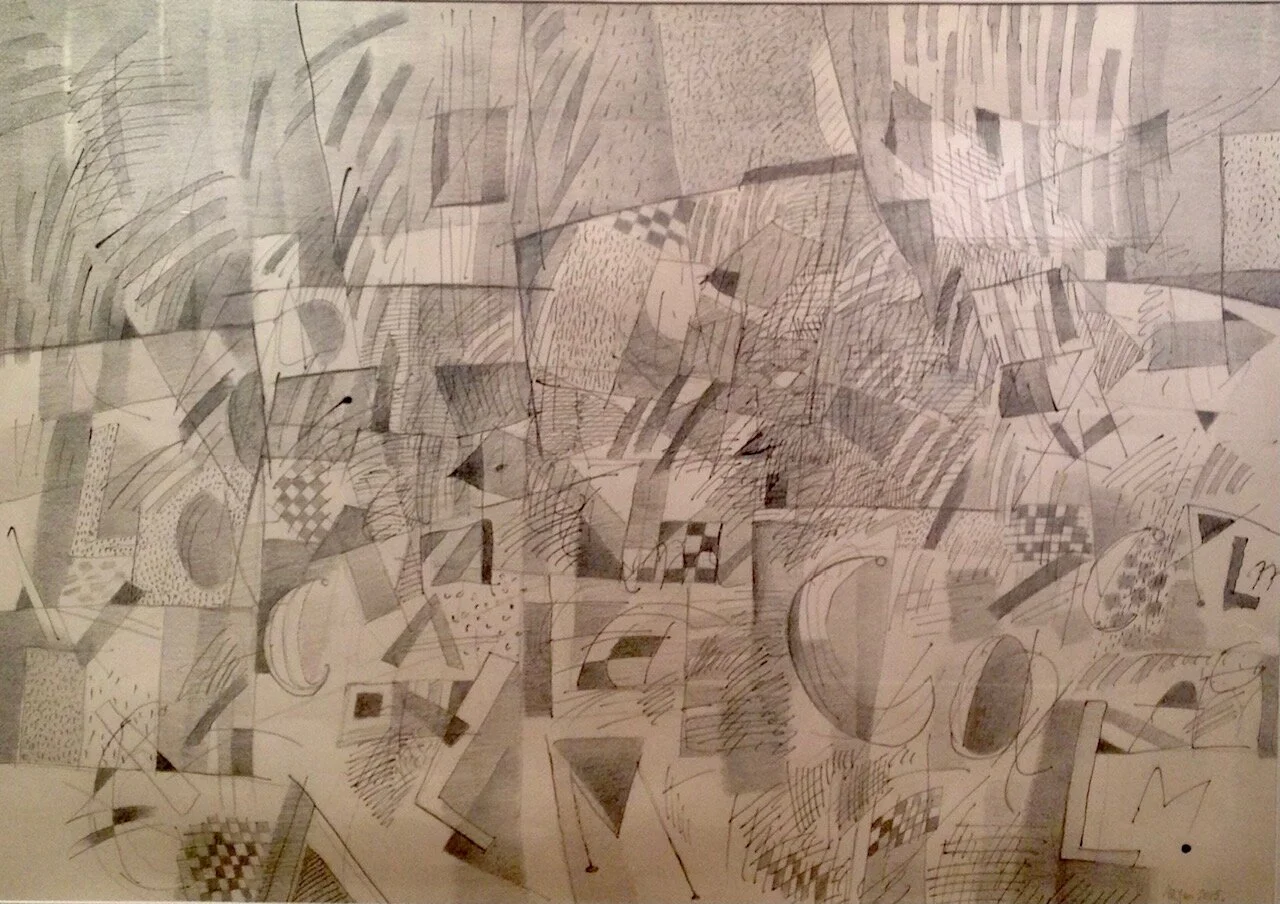

But still she has her paper, her pencils, her charcoal — these the items lifting her now. And on that paper her travels begin quietly — a simple, clean line scraped somewhere there in the white, and often in the color gray. Then more lines will come along, other grays. At some point shape and form begin to emerge, and also color, though not always — and in her case these colors do tend to remain on the more muted, modest end of the spectrum, “because they’re what I know.”

When eyeing her work, I often pull from it the impression that there’s something to be said, yet it shouldn’t have to be shouted. Perhaps this can also be said of her generation. So much quiet wisdom there, yet often it needs to be sought out. As opposed to my generation, wherein everyone seems in a race to show, to shout out, to selfie, to collect “likes” — with little wisdom there in all that brightness, that noise.

But I digress.

Back to my grandmother, her work. Of course it can vary. So much depends on the day, her mood, whatever the paper tells her to do. Often the page calls for letters; as in, letters like these, plucked from the alphabet, only not always strung together in a certain order as they are here but placed randomly or alone. For instance an H might float freely in a corner, or teeter from the edge of a table, or even find itself inside of a three-dimensional cube among other letters inside of other cubes, and all of these cubes may be tumbling across the page, like dice.

These letters may be plainly visible or somehow hidden, obscured partially in a swath of color. Occasionally the letters will find themselves as part of words, even English words — calm, for example, has made it into several of Babcia’s works. It’s one of the few English words she knows, and her favorite. She loves the sound. Calm. She says it’s a sound that suits the meaning of the word so much better than its Polish counterpart, spokojna. And that word, that sound, that feeling — calm — that, she says, is the very thing she’s chasing now, here in this stage of her life.

As for those freestanding letters, or those letters placed inside of tumbling cubes, I’ve asked her why.

“Why? Because why not? Letters are extraordinary. They’re art.” She’ll say this to me in Polish, but slowly so I’ll understand. And she’ll go on: “Think about it. Once, letters didn’t exist. …” And then someone thought of this visual thing, a symbol to indicate a sound. Then another. Then another. Can you imagine? One day someone thought of the letter A, and decided to make it look like a tent. Then, for the sound beh, someone made a B, with those two circles leaning against a line.

“And now these symbols are everything, they’re everywhere. They’re how we express, communicate, understand each other. So you tell me,” my grandmother will ask, “is that not art?”

Thus the letters appear. I’ve spotted them in illustrations of hers dating back to the seventies. Letters to be considered rather than passed over. And in this way a letter can be like a person, a story, a place.

And I suppose this is why I’m here. This is my best answer to the question I often get from the locals here, once they hear my terrible Polish, my American accent: A co pan robisz w Polsce?; And what, sir, are you doing in Poland?

I’m here because of her. Because there are some people and certain places you don’t just go to see; you go to them because doing so reminds you how to see. For me now, this is that sort of person, and Poland has become that sort of place. And so I write about her, and about here.

And look, here she is, and here she’s right: indeed someone once created the A, and then the B, and now even you’re here, too, and we’re all connected somehow, somewhere here in these lines of letters and these letters about lines. Lines that lead us always, somehow, to each other.

Maria Jastrzebska, or “Mucha”

Some of her assorted works, from 1977 to 2021…

For more information about Maria Jastrzebska, or to see examples of her drypoint currently held by the Zacheta National Gallery of Art, please click here.

Post inspired by my work, Old World Avenue.

Text and photos © Jan Gajewski / Illustrations © Maria Jastrzebska