Mom’s book, her beginning

July 19, 2023. Los Angeles.

Mom’s book, it’s encased inside of a laminated binder from Staples, the office store. I know this because the Staples logo is on the removable leaflet still tucked there into the spine. The pages inside the binder, seventy two of them, they’re held together by a metal clamp and alternate between text and photos of her paintings, with the text pages usually brief, two or three paragraphs at a time to describe a moment or the pictures to come.

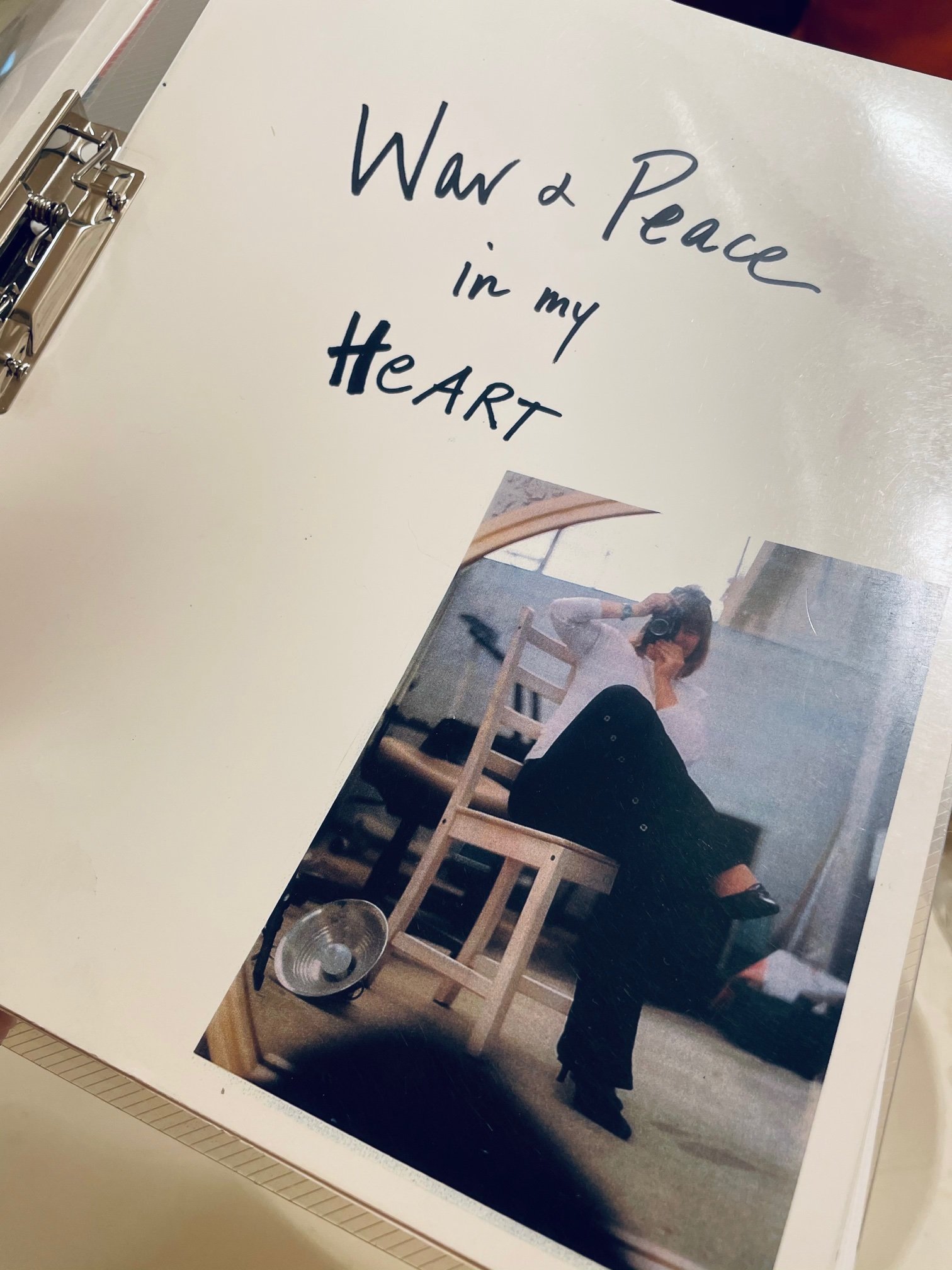

Mom’s original title?

War and Peace in my Heart

Mom’s name? It’s nowhere to be found.

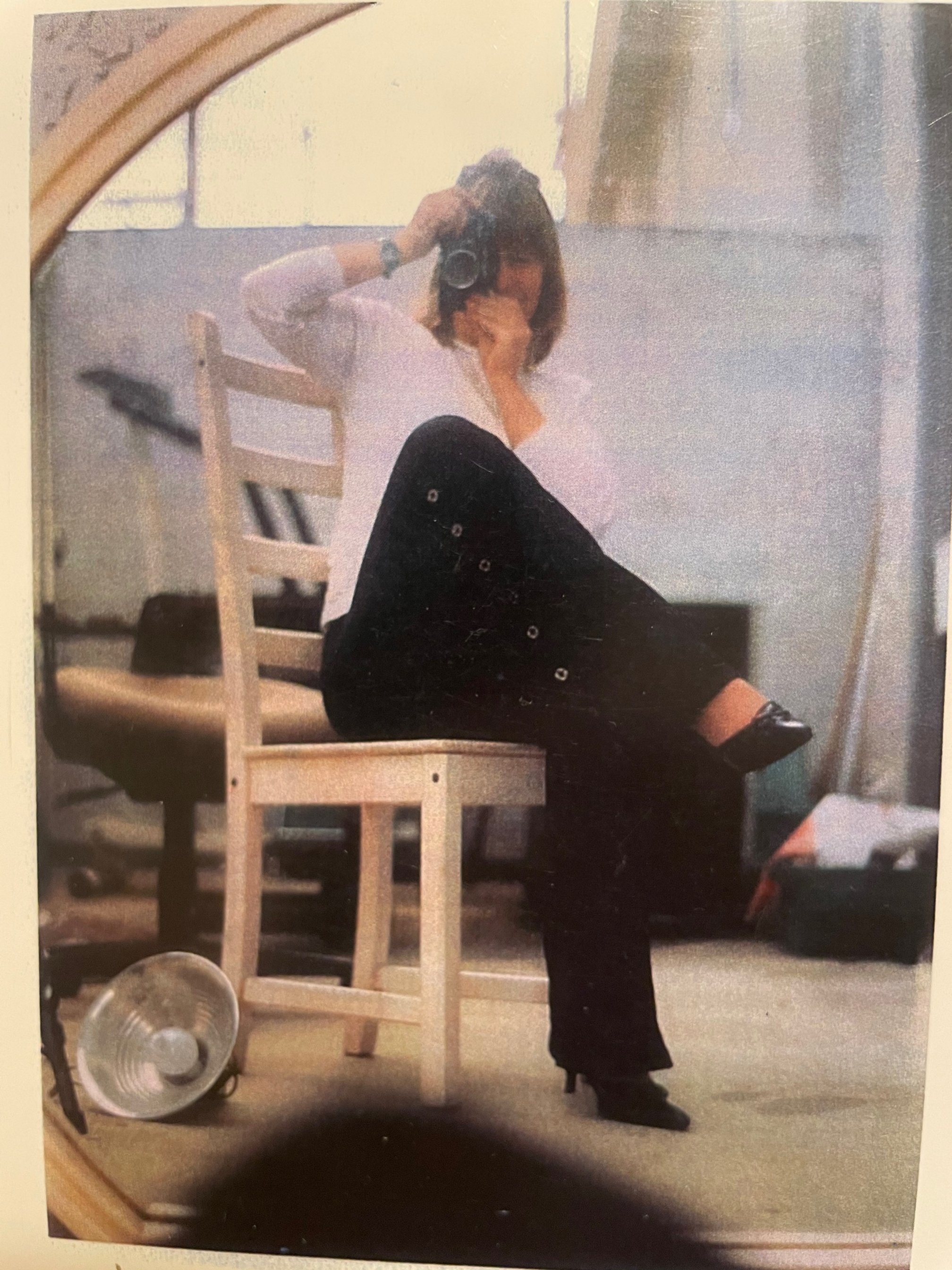

On the bottom corner of the handwritten title page, there is only a self portrait: she’s taking a photo of her reflection, and in that mirror is Mom when she was younger, difficult for me to say exactly how much younger because her face is mostly hidden there behind an old camera she’s squinting through. In the photo, she’s sitting on a pale wooden chair, is wearing heels (for her, unusual), and has one leg crossed over the other.

And now I can’t make this up:

Just now, writing this down into my sketchbook here on my lap, I realize my own two feet are now propped up on that same pale wooden chair. Really: I didn’t plan this. And really: here is more proof that Mom never throws a thing away. I noticed this coincidence when I just now paused to look up from the page and take a sip of drink. What do I see there on the chair, besides my ugly feet? I see a couple pieces of mail, and a sketchbook, and a remote control, and a placemat that reads in large cursive letters, Blessed. Hanging off the back of the chair, I see the straps of a couple of mom’s handbags (recently I donated probably a hundred others). And some wind chimes, because why not. And then behind the chair, the old television set that still plays Mom’s countless VHS tapes, and the folded-up walker we received at the hospital but remains just there, in the background, unnecessary still.

Really: what are the odds of this?

Anyway, this chair, and the things on it: I suppose here is Mom in a nutshell. An old thing cherished, not thrown away. And the chimes for a bit of music, or aesthetic, or both. And that word there, looking back at the room: Blessed.

But maybe that’s enough now of one stupid or not so stupid chair.

Let’s get to her words now, her book, her own beginning.

I was painting in dark colors when I came to the US in 1979. I left my troubled country right before all this happened: martial law, crackdown of the old system, the Berlin Wall falling. I left my family there, hoping that nothing bad would happen to them.

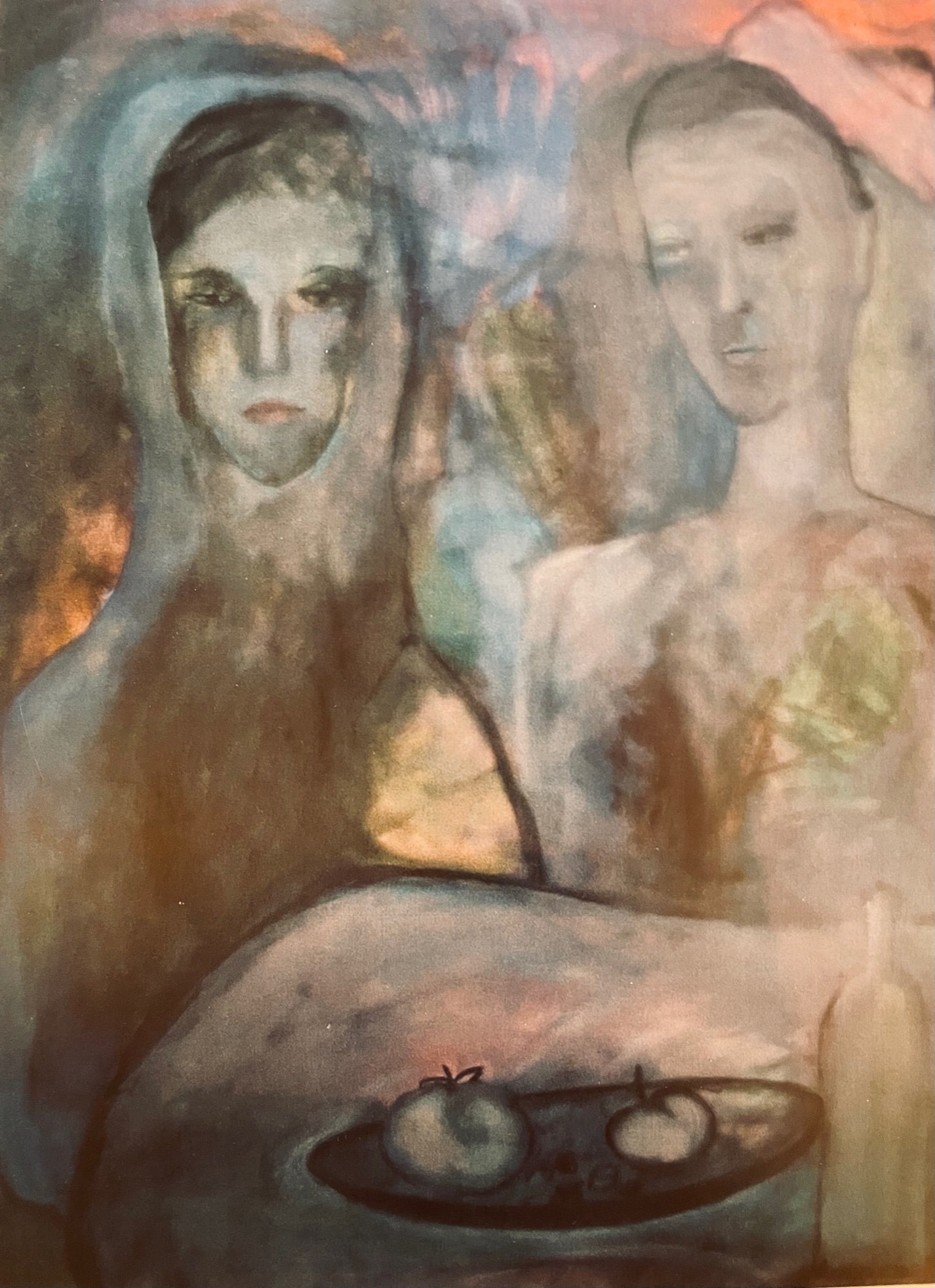

Dark colors in my paintings reflected my soul, dark tones symbolized trouble. In the 80s all my paintings were gray, figurative, somewhat cubistic.

I left most of them in Houston, in private collections. A few people would collect my paintings during those years. Lydia and John Doerr, Michelle Huebner, Dagmara Bienko, Perry and Mike McCall, George Malone, Evelyn and Charles Warnky, David Greenfield. I sold two pieces through Pembroke Gallery.

blue portraits 2’x3’, tempera on paper

When my children went to preschool I started to work, part time, at the local Community College. I got a divorce in 1989 and moved to a one-bedroom apartment with my two boys. I freed my soul but survival was tough. I was hoping to make extra money I needed with my art.

The process of making art is more fascinating to me than art as a final product. To some degree you are in charge of the process, but to some extent it is also a total surprise.

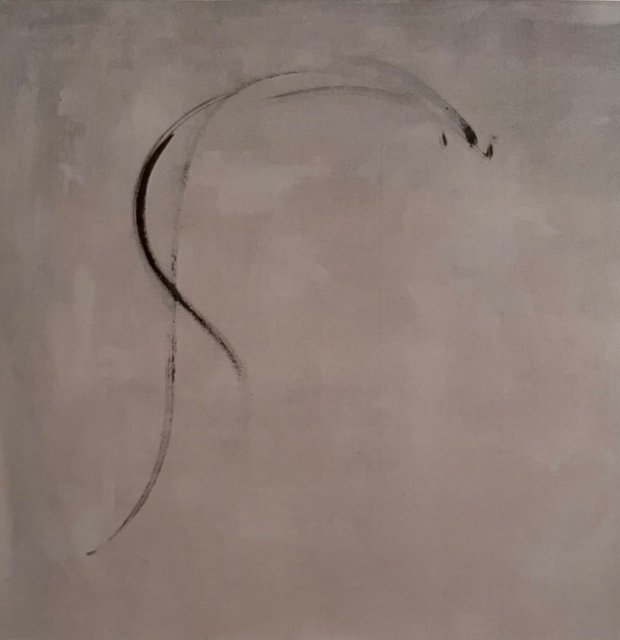

What makes me paint a line? Is a line in a painting as a musical note is in a symphony?

linear painting, oil on canvas, 40x40

On my job I was barely surviving but the experience was great — people from the Art Department welcomed me without reservations, maybe ……. knowing that this was my first job in this country. They were all my good friends.

Spoken English was not a problem, but my writing was far from perfection. I took a course in creative writing. In my class we wrote short essays on given subjects. Once I even got an A grade with a note: “well expressed.” I don’t ever remember being prouder. “If I wrote an “A” essay in English, I thought, “this could mean that I really belong here.”

~~~

[Here in the book, on the following page, my mother includes the essay which earned her the A, and that note of “well expressed.” The essay is titled “Turning Point”, and is dated 1990. Here is the essay:

~~~

Three years ago I had a chance to start a new life. It was when my friends called to tell me about this great new opportunity offered by Hermann Hospital. I decided to follow their advice and see if I could get into the medical field the fastest way and without paying. My finances and my future were at stake. I was then an artist, trying to make my living by teaching and selling art. My teaching job was uncertain. With my art I was moving too slowly. I wanted ten paintings consistent in style, I was constantly experimenting, my time was limited. My children were growing fast and I was the only provider. I followed my friend’s advice and entered the exam. I was stunned when they told me that I had passed. For someone like me who was out of school for more than a decade passing English, algebra and math was quite an achievement. I also passed an interview. My friends were ecstatic and I was proud. I belonged to the lucky sixteen percent of all people who had made it. I was going to start my new job with “hands on” training on December 15.

Christmas was coming and here I was — given my new opportunity. I remembered watching my son’s baseball game one cold dreary evening. I imagined getting on a bus at 6:30 am each day to a hospital and leaving my children with the chore of making their breakfast all by themselves. Yet, there was something else that I was about to abandon. Two weeks before I had rented a studio space where for the first time I was going to do work as an artist. It was a dark space in someone’s house that smelled like mildew. It was the first art studio that I ever had. It was an entrance to the world, my own world that I was about to explore. Creating art is a process, not an act. It is creating yourself in many ways and once you start it is difficult to leave yourself “half done.”

I was standing there, that cold, rainy evening, watching my son and thinking about things that I was going to abandon.

I never got on that bus on December 15. Instead — I kept my job teaching a few art courses at a community college, and I went to my dark studio to continue the most difficult and complicated journey that I ever took — within my own soul.

“Music”, oil on canvas 5x8

My mother’s name is Anna Gajewska, born Anna Katarzyna Jastrzebska in Warsaw, Poland, in 1953. She entered the world from her mother’s womb rear-end first, which meant that she was always going to be a rebel. And this story — her story — is to be continued.