Mom’s book, our Liberty

Sometimes Liberty

Is to conquer yourself

Sometimes Liberty is to have a home

Sometimes Liberty is to get a meal

Sometimes Liberty is not to be alone

Sometimes Liberty

Is to see the ocean

For some it is to sacrifice and die

Sometimes Liberty is to breathe on your own

Sometimes Liberty is to come home alive

I wish that we all will be free someday

Liberty means no longer being lost

I hope that everything happens for a reason

I want to think that our sorrows are the soil

— Anna Gajewska

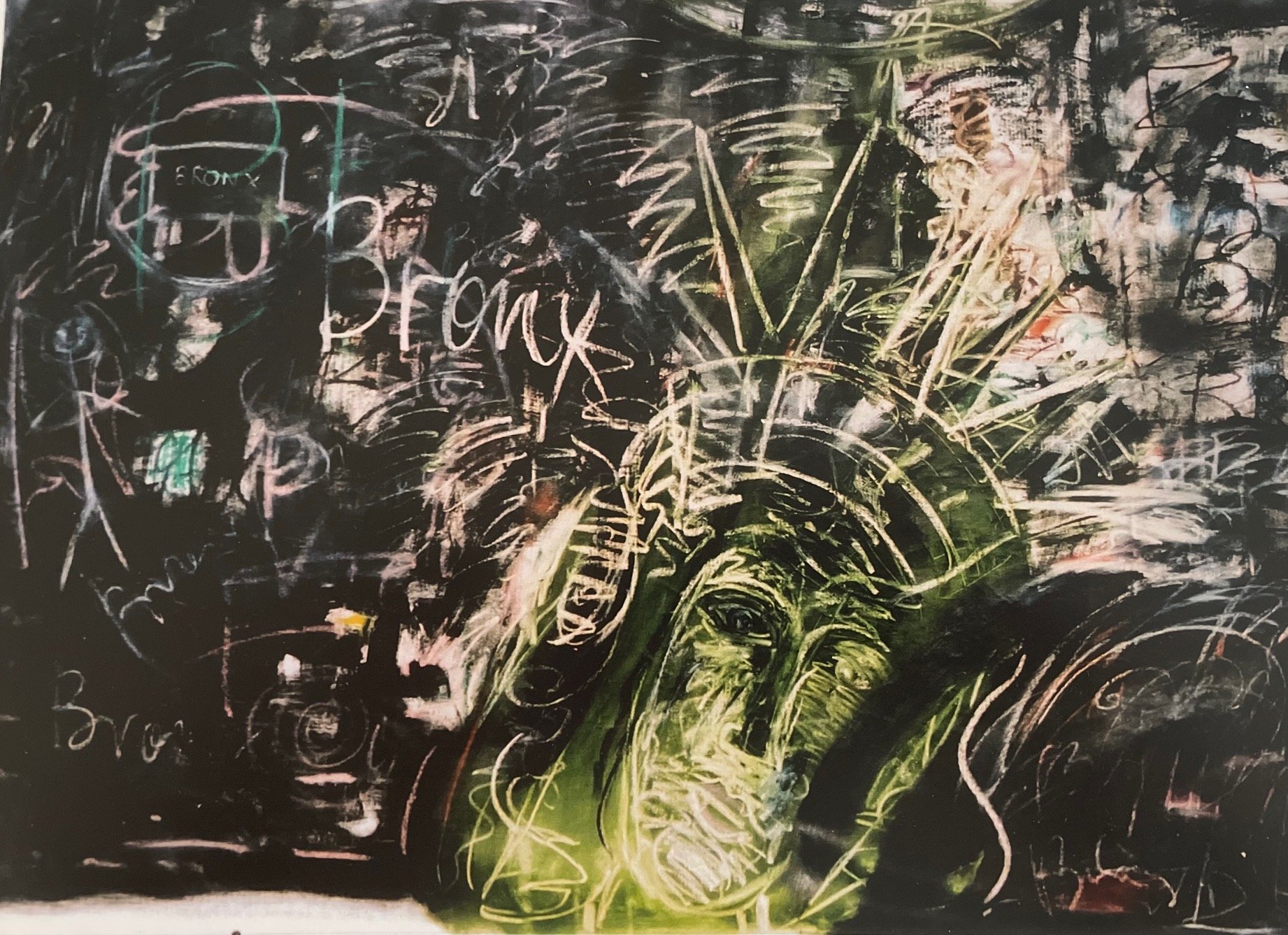

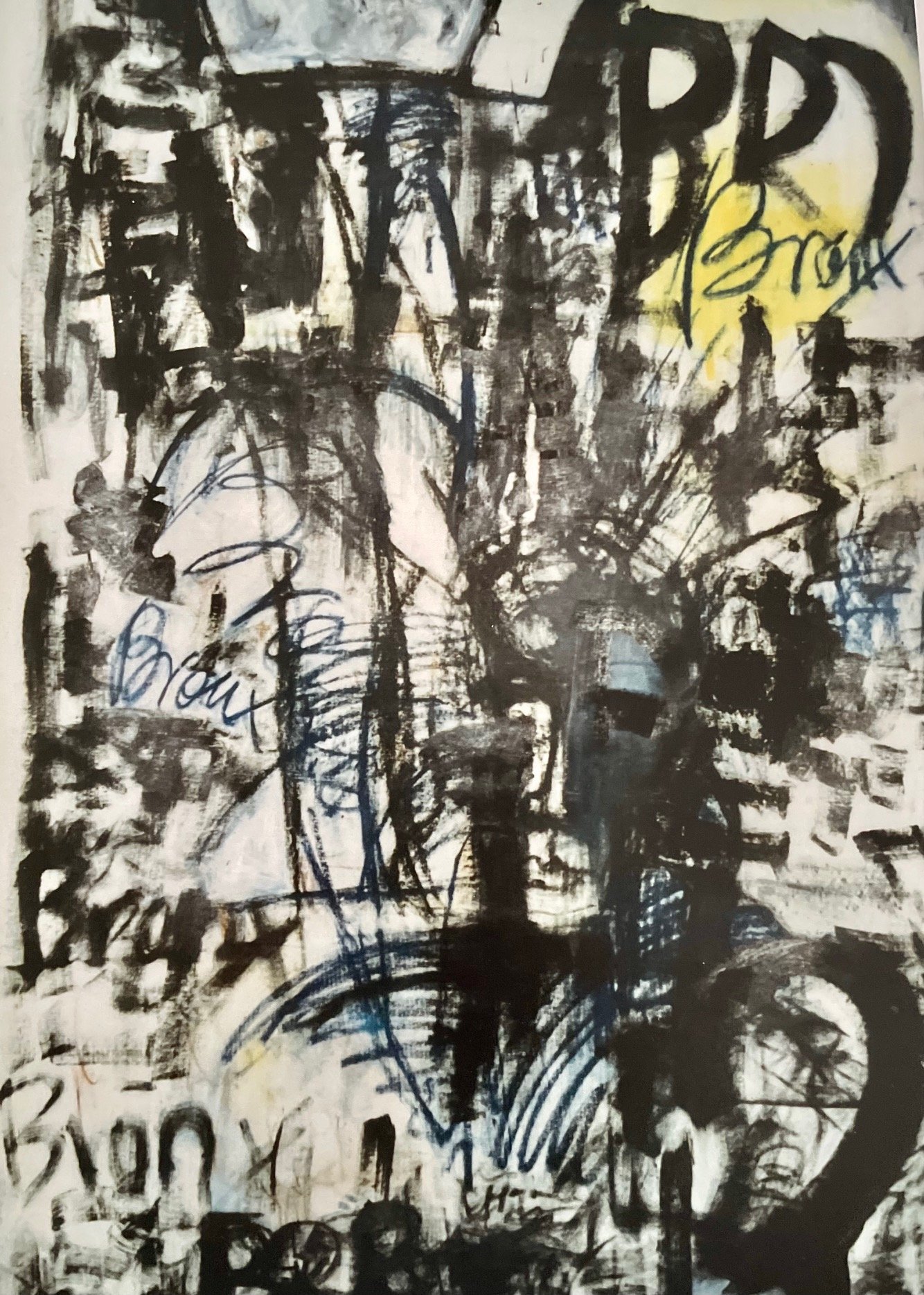

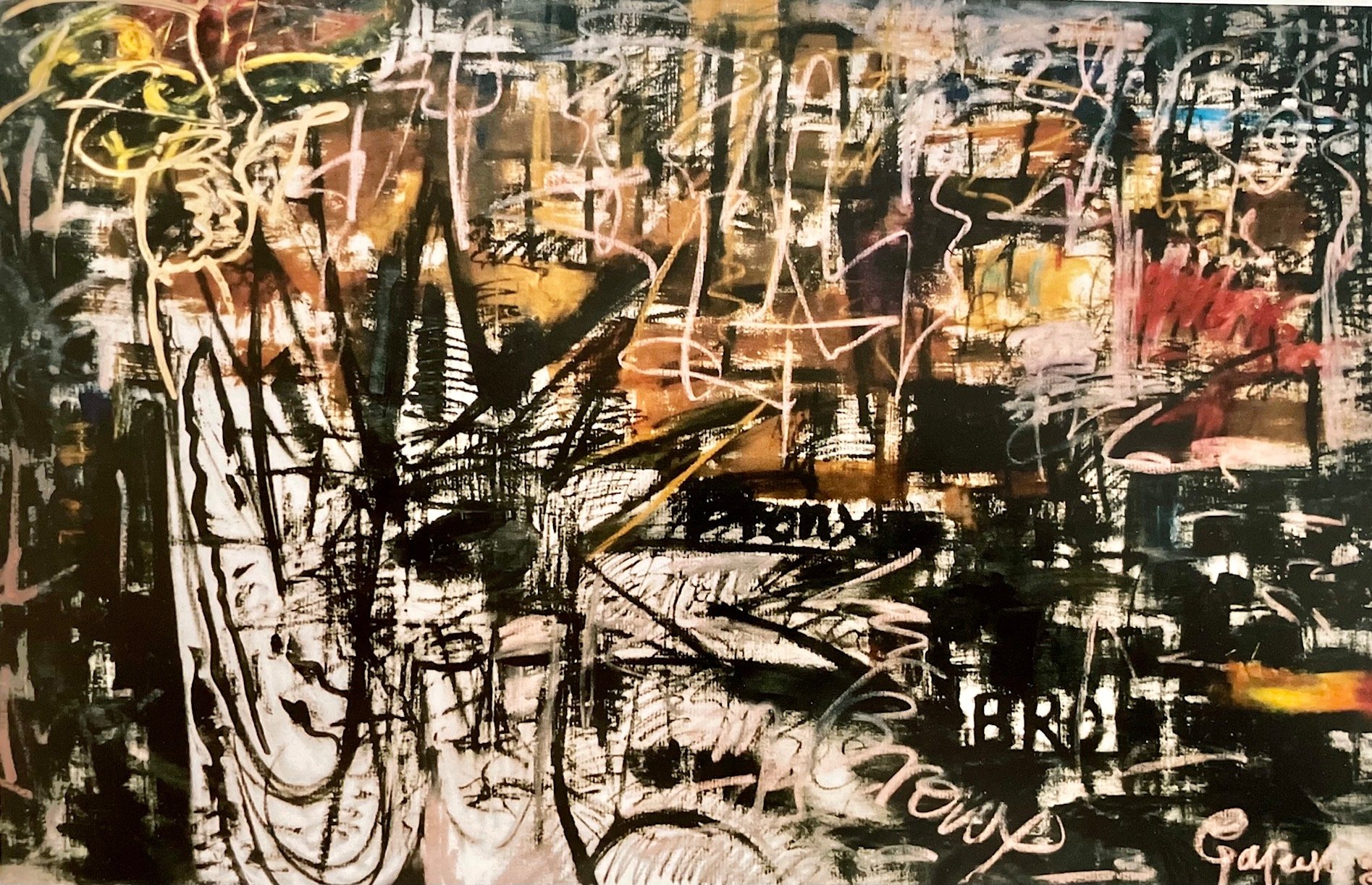

The poem above is the sixth page of my mother’s story, that little book she created for gallery decision-makers sometime around 2006, for when they would inevitably ask for more, more of her story, her resumé — for perhaps her worth. Pictures of three of her Liberty Series paintings follow, and after that she moves on. Yet here and now, looking back on this, reading this over, a son finds it almost strange his mother writes so little of New York within that little book of hers, of the two trips she took there which inspired those paintings, and that poem. Or is it that New York stands out as a more important peg in our story to me, the son, than it ever meant to her? And so to answer this, to put this part of the story down, a son takes liberty here to add. To dig. To ask. All this, to get this part of the story right. Because for me, New York means so much. For me, New York was always our little miracle, our light up there in the fog.

To begin: when I first read over those lines of the poem, and my mind peered back, I couldn’t see, couldn’t remember it all, every little bit. Like: how did Mom manage to go there — first alone, and then later with me? And what was the pretext? Before I discussed it with her further, I wrote down only what I first remembered: that Mom had gone to New York twice, and I believe that first trip had something to do with her art, but then I found it strange she was able to go at all considering how my father notoriously didn’t give her any spending money when they were still together — or believed in her artistic pursuits whatsoever. He would always call it, as he would call any artistic endeavor (including my own writing, later on), the stuff of ‘Pie in the sky’ dreams.

And that first time my mother left Houston for New York, I remember also that this was the first time I ever separated from my mother for more than a day. A child remembers such things, I think. And here I remember this: crying when saying goodbye to her at the airport, and then Dad taking me to McDonald’s on the way home, seemingly amused at my heartbreak. I remember him then being further amused that I could eat my McDonald’s hamburgers so fast, so furiously, and asking me if I wanted another, and then another, he was enjoying seeing just how much I could actually eat, and I just kept at it, unwrapping and eating, and he just kept laughing, and then later that night I remember vomiting — vomiting like I’d never vomit again, and vomiting for days after, at school, at home. It became so bad that my father had to pick me up from school one day and take me to a doctor, and that doctor prescribed for me some kind of diet that included crackers, bananas, and Sprite in an effort to settle my stomach.

But that second trip, when I actually joined Mom on a plane to New York? Here, a son remembers only happy flashes, and flashes I’ve found here in paper form as well, among the mess here at Mom’s. I’ve found them in the old program of an art exhibition held for my mother and grandmother at Cal Poly Pomona University back in the 2000s, the two of them exhibited in a show called A Mother and Daughter As Artists, A World Apart. In this exhibition program, on Page 1, here I find my own introduction to that show:

I remember telling my mom that the people looked like ants. My forehead was pressed against a cold glass window, and we were looking down from the observation floor of the World Trade Center.

I remember my mom saying, “Look! There it is!” and then seeing it in the fog, the glowing torch of the Statue of Liberty, floating there beyond another pane of glass, this one belonging to the humming Staten Island Ferry.

I remember the brush in my mother’s hand sometime later, how it swirled into water and varying shades of paint time and time again and then scratched against the canvas with such ease. We were back home in Houston now but this was still a window, one made of color and canvas, and through it I saw two women more clearly than before: Lady Liberty no longer in her fog, and my mother, her feelings, memories and dreams all there in these swirling dark shades.

I remember the conversation my grandmother and I shared this past summer in her Warsaw home. I’d asked why she generally preferred artworks of a lighter nature, a penchant that so often led her to paint or draw for children. She said it was because her war-torn childhood was too dark, a place perhaps better left behind, and it was through art that she could always fly away. It’s no accident that we call her Mucha, or Fly.

In life we escape through squares. Movie screens, television sets, the pages of a book. Every square is a window to somewhere else, and for Anna Gajewska and Maria Jastrzebska, these windows have often made far more sense than the world around them. These two artiss have spent their lives creating windows through which to jump, and it is my honor to welcome you now into their world, a place that’s never perfect, sometimes scary and often unclear, but a place where the walls always dance with these squares of infinite possibility. Without further ado I invite you to have a look, and maybe fly away.

— From a proud son and grandson, Jan Gajewski

People came and people marveled on that Opening Night in Pomona. This I remember also. I was there, of course. So was my grandmother, all the way from Warsaw, and bless her heart, she did her very best to nod her head when someone came to her speaking English. It was a great night. A marvelous night. Did anyone buy a painting then or during the entirety of the show? I don’t remember, I don’t care. But I remember that night, and I’ll hold onto the memories of that trip to New York which inspired Mom’s Liberty Series paintings which appeared there in Pomona.

And so, to fill in the rest of this tale, this part of my mother’s story and perhaps my own — New York will stand tall for me for the rest of my life, not only because of that first experience of it but for what it meant to me later, when I moved there, explored my own work and soul there — I sat by Mom’s bed yesterday, Mom resting there between meals, between medications, and I asked her about it all. I wanted to know what I didn’t know. I wanted to know about the gaps.

When we went to New York, did that trip have something to do with your art?

Just adventure.

I thought before, when I got sick and stayed with Dad, that it had something to do with your work. …

I went to galleries. To see galleries and to talk to them about my art.

And Dad allowed you?

You know, I [too] am surprised that things like this happened. I think that was once. Must have been once. Probably not for his money. I probably got this money from somewhere, but it was horrible that I left you there. Because you had some bad experience.

But that was not your fault, that was Dad’s fault.

Yeah, that he let me (travel), very strange. But when I went with you, I didn’t go to galleries. Just to show you New York. We stayed in Long Island.

Yes, I have these memories of that house, the train, flashes of Madison Square Garden, the Intrepid, and the Statue.

That was just to show you New York. It was when we lived in Georgetown [an apartment complex in Houston], right? It must have been. … It was after the divorce. … It was after. … I was still hoping that I can do some business. I was weird, to think that. I must have been really desperate.

So that first trip to New York [before the divorce] must have been some trip for you.

You know, I had these videos of my backgrounds for ballet companies. I was going to ballet companies. Yeah. I was hoping to get some work as a stage designer. But you know, those people were very hard to… I really had not much knowledge about business, how to approach people. I don’t know what the hell I was doing. … But I saw for myself that the business of art is really dead. Because they offer me a show (only) if I can guarantee them $5000. And I saw for myself then that this is, you know… something is wrong with that. Something is wrong with that. And I remember it was kind of humiliating because so many artists lived there. And I went to this art gallery and I was waiting and I was like — waiting to meet someone, or I wanted to see someone. And those secretaries in the galleries would say, ‘Oh, one of those.’ One of those. And you know what? At this point, I’ve had it.

But that was pretty gutsy of you to go there.

You know, someone in that Houston Museum of Art, the director. He liked [my work]. And Leo Castelli — he was the biggest agent in New York, and I thought maybe they knew each other. So I said, when I … [when I saw Castelli] that I was sent by this guy. And no — it was not true.

You didn’t ask the art director in Houston if you could say that?

No. I was doing everything wrong, I’m telling you.

No. you gave it a shot. But so wait, you talked with [Castelli]?

Yes, with the most famous agent. Leo Castelli.

How did you even get an appointment with him?

I just showed up, at his gallery – he represented Andy Warhol. [Mom laughs here, or should I say giggles.]

Good for you. That takes guts.

Guts and desperation.

But you gave it a shot. It’s good.

Here, Mom, in bed, thinking back over her life, back to that New York and back also to when she once tried to write a more ambitious, full book about her life — a project she started but then stopped — here my mom began to cry. She said she couldn’t do it, write that longer book. She said she always started, then stopped. I asked her why.

So much guilt, towards you guys. [me and my brother] … Because I was doing some things that I shouldn’t have been doing. This art thing, that was crazy.

It’s not crazy, it’s you. And you went after what you wanted to go after. And you doing that was the reason when Dad was always telling me not to do stuff and I thought, Fuck that, I will do what I want to do. That was because you — you showed me that going for it in art meant something. So there is absolutely no guilt involved. I’m amazed by your New York trip, Mom. That’s incredible.

But you know – like… living with Dad was a little like being in prison. And sometimes prisoners escape and do crazy stuff. [fights back tears]

Please, never feel guilt over how you handled anything.

Somehow, when I was writing this book about myself, it was just too painful. I would get to the… I don’t know. I would get to some point. [And stop.] You know, Dad was the element that… I couldn’t write about Dad.

Because it was too painful.

Yeah. But then. It’s good when you do it on purpose — for another purpose other than writing a book about yourself. If you write a book about yourself for no reason it’s bad, but this little one, this little script you were reading [for gallery people], I wrote it with a purpose. I got really mad, in a way. Like it was a closure. It was like, fuck this.

[But] in a way, I understand the galleries. Because, you know, this business, really, I understand why they were doing this. If I had a gallery I would do the same thing, I mean who can sacrifice themselves for ‘one of them’? [she laughs] ‘One of them.’ …

Today, writing this, I remember other things about our New York. I remember the taste of mustard and happiness on my tongue as Mom and I stopped to eat a hot dog on the sidewalk. I remember standing in front of the Madison Square Garden marquee and it showing the temperature — 63 degrees — and me thinking, So this is what 63 degrees feels like. And maybe also: this is what happiness feels like.

Yes, for me, New York was the miracle. And I will forever be thankful that Mom was ‘One of those.’ And for mom’s work, for her bravery to go after what she dreamed of. For her bravery to leave Dad. And of course for what came out of that happening on the Staten Island Ferry — the two of us, there among tired faces going home from a long day in Manhattan, but the two of us looking through that window and up through the fog, up to that emerging light… Mom’s work, those Liberty canvases to come, these held for me some greater truths. About life, about us. I could die tomorrow along with my mother and be thankful for all of this, thankful to experience such a moment, such a trip, such a flash of light there within this fog of our existence.

And that’s it. That’s all of it, I suppose. That’s liberty — for me now.