Signs (so far)

But Mom and I, we’re always looking for signs…

I’d written that down, and we’d talked about it. I suppose we, the living, do this to cope. We look for signs to feel less alone. To put meaning into hurt. To soften the landing of all those shiny sparkling falling pieces. There needs to be something else — because otherwise what would it be for. There needs to be something else — because otherwise we’re just more alone. Because the alternative is too sad.

So we look for signs. Or maybe just some of us do. The ones who need them. Mom was one such person. Now I am. And I did ask her before: Hey, hey Mom, if you’re not too busy, could you send me some? She said sure.

So was that her?

~

Was that her who decided to go, only once I’d fallen asleep?

~

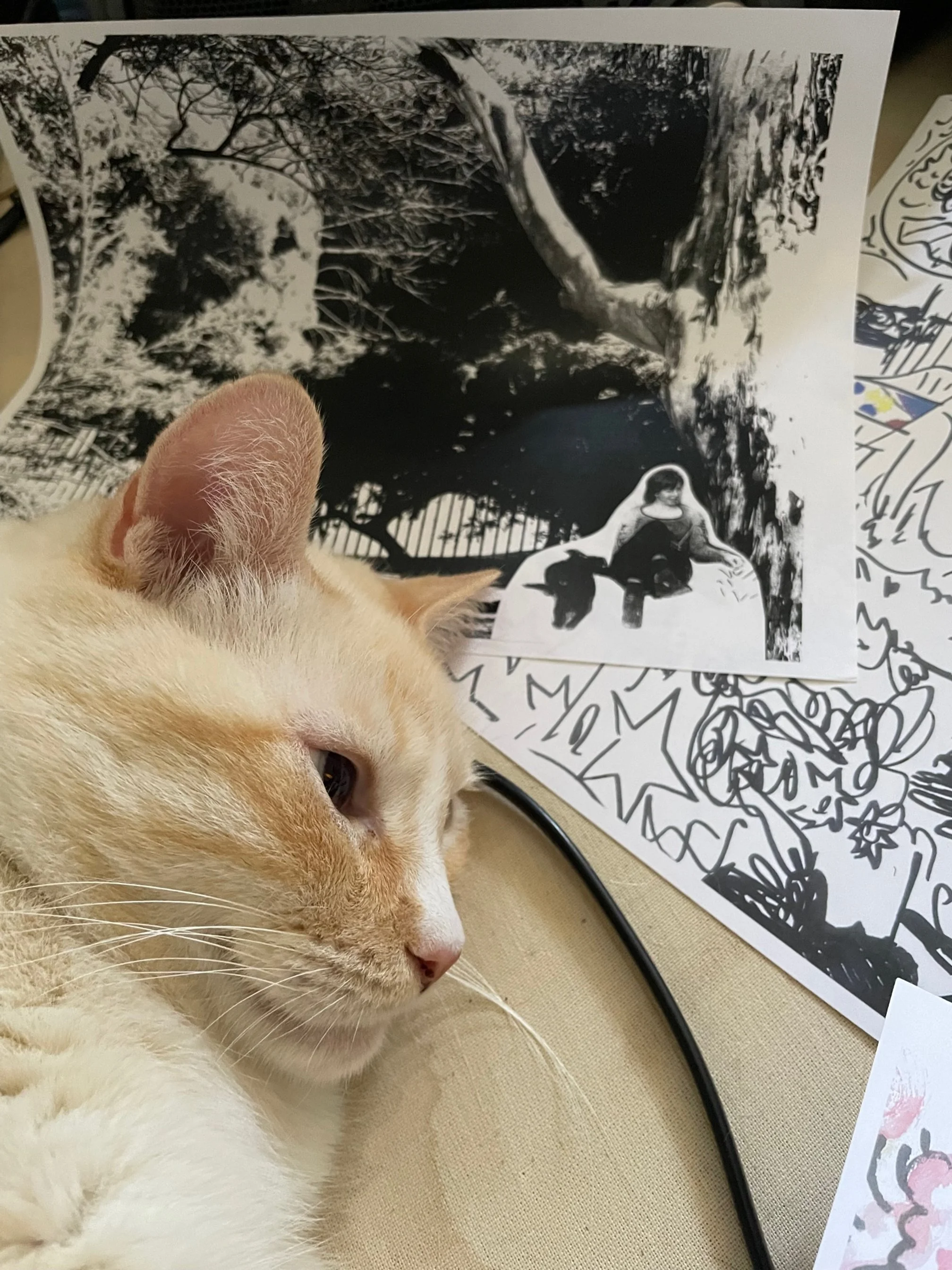

Was that her who’d sent Snowy up to me, to us — big, fat, golden Snowy — up onto that bed where we both were, where Snowy never tried to go before? Snowy did get night jitters time to time, would always like plopping onto us or next to us in the darkest hours, but never had he jumped there, onto that bed. He’d only just looked at it from the other one, looked at Mom, at me, at the lines, but kept a distance.

Then there he was, at our feet where there were no rails — it took him two or three times, I think, but he got up there. And I tried to tell him, hey, hey no — I didn’t want him to get too close to her side, to where the cancer was, to hurt her or begin playing with one of the lines. So when he just kept on pushing to be that close, finally I relented and said OK, OK Snowy let’s compromise: let’s go over to the other bed together, just for a bit. You and me. You can rest and purr your worries onto me there, tell me your stories, your pains. And he did. He plopped down on to me, heavily onto stomach and chest, with his big Garfield face two inches from my nose, and he told me everything. And I pet him and told him it was OK. Told him don’t worry, she can still hear you, and he meowed his raspy meow that would always make her laugh — he did this exuberantly then, several times.

Was it her who wanted us together there? Calming each other as we both kept looking over, at her back and side, at the rise and fall, the rise and fall of breathing?

I’ll be thinking about this forever. Probably will be thinking about it in my own moment, my own time, on that same kind of bed one day. How I’d wished I’d stayed. Right next to her. How I wish I hadn’t fallen asleep.

But could it have been her? The nurse told me nine of ten people, in her experience, go when they’re alone. When family finally leaves — goes to the bathroom, or goes to sleep. Then—.

~

Was it her who woke us up only two hours later, woke us once it was time?

My eyes blinked open. Saw no rise, no fall. Just a stillness there, and Snowy on the floor beneath that bed now — a place where he’d also never rested before.

~

~

Was that her who sent the bird onto that line? Was she actually the bird, was she actually that line?

After telling my brother, after we both cried and prayed there with her. After I’d read aloud her words, and our words together — let’s dance, let’s dance — after it I needed to begin the awful task of telling others. Needed to still myself, my breathing and tears. Needed to go outside. And on her patio, I sat there.

I sat and stared at the empty lounger where I’d watched her, listened to her. Where together we’d tilted our heads up into the raindrops and she’d said, “This is life.”

I called her brother, but got no answer. Again. No answer. Waited awhile longer. Texted my cousins to maybe get some other number for him. And as these messages went and came, as I waited and kept trying to still myself, I leaned back in that chair and my eyes drifted higher. And there, resting on a power line up overhead, was that bird. Just a single small bird, still. It seemed to be looking my way. Was that her?

I thought of her story — when Rocky died, and how she went to the park and the falcon came. Thought of how she believed that was Rocky, or his sign saying he was OK.

So was that her? For awhile we just sat like that in the quiet morning air. Me. The bird. Five minutes, ten minutes, fifteen minutes, twenty. We sat eyeing each other and I thought also of Mom saying she wished she’d have spent more time painting simple, clean lines, and here were simple, clean lines, lines with energy in them, and on one line, a simple bird.

My phone rang. Her brother, my uncle. I told him. Listened to his breathing, him grasping for stillness now. And only then, my ear to the phone listening, did I see the bird up there turning and flapping away.

~

Was it her who sent the sunset that evening, so brilliant, so orange? Like a fire in the great distance, a light Snowy and I looked into and tried to absorb.

~

Was it her who sent the hurricane — a hurricane? Coming here? To L.A.?

~

And was it her that night — after the sunset, and before the rains — who took me to that store, that man, over by that door?

I’d gone to fetch groceries before the storm, where I’d always gone, for our bubbly and such. On my way out I heard him before I saw him: “'Scuse me sir, spare some change?” Sorry no, I said, just walking. This was instinctual. Some awful reflex we get programmed with. Not even sure if I looked over. Then I stopped. I felt for change in my pocket and did feel some coins and bills there. And I thought: today I stop, today I give. Today I don’t be so on my own way.

So I turned, scooped the coins from my pocket, and saw the man then for the first time really as he stood coming up to me. Skinny, long blond hair, some dirty clothes and dried blood on his face — the blood, from the sun maybe, or someone, or some life. “Thank you so much, sir,” he said as I dropped the coins into his hand. “I just want to get some food for my cat.”

I looked. Looked behind him. Only then did I see it there, a little cat also, resting by the door and a little crate.

Come on, Mom. Now you’re laying it on a little thick.

He took the change, went quickly inside. The cat just rested there, unmoving, waiting, eyes closed. I backed away, went to my car. Then stopped again, because dammit I am my mother’s son, and I know what Mom would do. So I went back. And as he was coming out with something in his hand — I don’t know what, could have been a can of soft food — I fished for the rest of what I had, the bills, and said, “Man listen: my Mom passed away today. And Mom loved her cats. So this, this is from Mom.”

“Aw I’m so sorry. I really appreciate it, man. Yeah, this one here, she can’t walk much no more. But she’s been with me seventeen years.”

Seventeen years — same as Rocky. Same as Snowy.

~

~

Was it her who sent Ewa and Andrzej to my grandmother back in Poland?

This visit, this time and day already planned, yet now it seemed too perfect, too ordained. There is no good way to tell a mother she’s lost her child. But to call when they would be there, to cry with her, spend the rest of the day with her …

“Babcia is happy, I think — see, she has now… Geryszewskis. … Babcia is a very lucky ….”

She’d said this out on the patio then.

But now, now was she saying it again?

~

Was it her who sent just those soft rains in the morning to start, a patter there on her window, a nice way to wake, to meet the day after?

Was it her who sent me outside into the heavier rains a few hours later — just then?

It came to a point where I longed to feel that rain, feel her maybe, so out I went as it grew, but before going I needed to put on something. My eyes landed on the one thing I for some reason hadn’t thrown into a donation bag from the shelf over by her door. I’d done that days ago — there had been shoes there, stacks of her sneakers and boots, and I’d thrown them all into a bag, now in my car. But I’d left just one thing on that shelf — her big, ugly yellow windbreaker (sorry, Mom), her waterproof jacket that was always so baggy, so strange really, like something a parking attendant at Dodger Stadium might wear. Mom: why hadn’t you ever gotten a nicer windbreaker? Wasn’t this one much too big? Too baggy? And why the name of some Spanish soccer cup on it, when you’ve never even watched any soccer? But this was her windbreaker, she wore and trusted it, and maybe liked it because it was big, because it was yellow. Yellow was one of her Colors. Yellow was Van Gogh, was sunflowers, was eternity.

So I put it on. It felt kind of like a hug, and together then we went for a walk in the rain. We walked the back streets nearby, where the nicer homes were. We looked up and saw more birds on more lines, looking down at this big yellow blob now passing.

Then, from the pocket of that big yellow jacket, my phone began buzzing wildly, strangely. I looked. Held it up in the rain. And saw a yellow triangle with an exclamation point there on the screen. An alarm:

Emergency Alert

Earthquake Detected! Drop, Cover, Hold On. Protect Yourself. - USGS ShakeAlert

Alright, Mom. I get it now. You’re having a little fun now. Some fun with me maybe. But is this not a bit dramatic?

But yes, yes sure I’ll join you. In our yellow coat, in the rain, in the middle of the street, let’s dance.

~

And that would have been a good ending to this one, eh Mom? A button, just like your button.

But then you kept them coming:

Next day — the sun back out, a blood drive nearby, and you sent me there, or him there.

You had me on that gurney at the Red Cross, and the man you assigned to me, my arm my vein, was that man from the Virgin Islands. He was mostly quiet as he tubed the arm, gave my hand something to squeeze, stuck the needle in. And as he monitored the flow, the small talk began. We spoke of the “hurricane” yesterday, and the earthquake — he’d lived by the epicenter, was on the phone with his bother back home, where there are “real” hurricanes, and he was in the midst of making fun of this one to his brother when his own alert arrived, and the ground began shaking. I told him I’d been outside when that happened. And he told me, “I’d been outside earlier, way earlier in the morning — I’d taken my wife to the ocean, to see the sunrise if we could even see the sunrise through the clouds. But just to be outside. Because her Mom had just passed away.”

I told him.

He told me, then, that he’d lost his own mother four months earlier, and his father ten months before that. Told me, “So you’re still kind of numb, yeah? Or in shock. It’s like that, at first. But you’ll see. It’ll change. There are different stages to it. Like you’ll feel one way now. Then feel just a little different after the service. It just changes. I’m still in it too. It just changes. But you’ll be OK.”

~

Then a text from Mom’s friend Annette, in the car, in response to me having told her what had happened over the weekend.

Oh Jan! I had a dream of her. … Now I know, she was coming to say goodbye. … I think I had the dream Friday night. I remember feeling sad when I woke up. I was going to call, to check in, I was afraid to. She looked very healthy and happy. Which is how I want to remember her. I think she had Fillow with her. She actually asked how I was doing. Like checking on me. She looked at peace. And then that was it.

Mom — was that you?

~

And finally (or for now): after the blood, after that text, I realized I was over by the Salvation Army. Had some more of Mom’s things in the back, those shoes from the shelf, some other clothes. So I went there, dropped those things into the trailer there in that big empty lot. The same lot where once there was a tennis ball, on the day I’d found Rocky’s book and had thoughts of him, and of Fillow, and I’d brought that ball home to Mom and she’d said, “It’s him. It’s Rocky.”

I put the donation bags in the trailer, as then, and drove away, as then. And then I saw a tennis ball. Yes another tennis ball, there alone on that same sea of asphalt. I kind of just laughed then. Thought: OK, OK maybe it’s not so special, a ball here. Maybe I’m just going crazy. Maybe a ball just always lands here — for some reason, some how.

But of course I drove up to it, just to give it a glance from the window. And I saw it then: on this ball, in an orange marker, was the letter K.

K — for Kasia? Kasia, the name Babcia and the rest of my family, calls her by?

Mom — Hey Mom — was that you?

Well I guess keep them coming, if you can. I’m going to need them still. Need you. After all, we have work to do. A book to finish.

But really — was it you?