Good is quiet

A friend texted me this as my plane was about to push back and taxi to the runway. I‘d been anxious, and complaining. Anxious about what awaited me on the other end of that flight — Mom, and the pain of losing — but complaining, simply, about the people around me. Across the aisle a man had sat down and taken off not just his shoes, but his socks? And was going to stay like this — barefoot? Meanwhile the two guys in front of me, giggling, had pushed their seats back to recline fully, before takeoff; everyone knows the rule, but they didn’t care, and now I could smell their shampoo.

I sighed, I texted. You look around on an airplane and you see what’s wrong with the world. No tact, no class, no common kindness. Of course there is goodness also, but these other guys irk me so much.

He texted back. Yeah, but we have to see the good. Some people do not see other people. No sympathy or empathy. But there is always good. Good is quiet very often.

This is why he’s my friend. And this line of his, it struck me. It was so true. I told him so, and he said, Feel free to make it yours and use it.

So here I am, making it mine and using it. Actually I’ve been doing this since then. And I think others could too: think it, use it, let it roll around in the mind as I have, within the loudness of every day. Good is quiet. Within these moments of anxiousness or irk. Good is quiet. Within all of what’s around, or on our screens.

Good is there always, but it gets lost, gets hidden. Good lives behind closed doors. Behind mountains. It doesn’t sell, doesn’t make the news. But even here, in the midst of these terrible days, I’ve seen and touched it, and sometimes it has kept me sane, kept me going. So to thank it, here I thought I might also share some of it. Give good some light.

To begin, I won’t go far. To begin I’ll speak of Mom, of course, and open a door — the door to her other room, a room I’ve barely mentioned, yet it’s a room that still holds remnants of a story that tells of my mother’s good more than any of her paintings or poems could.

See there? It’s almost empty now. And still. But there in the larger of the two bedrooms upstairs, not long ago, lived a cat. Her name was Swifty, and this fact may not be news to anyone who’s followed Mom’s story — she was an animal lover and cat person, clearly — but the twist in there was that Swifty was feral. A tiny thing, rarely seen nor heard. Except when she would hiss or go quickly hide. Swifty was Munka’s mother, and Mom always liked to tell the story of Swifty’s bravery, her heroism, of how it began: Swifty out in the carport — she’d come off the street and found a spot there to give birth — and then one day later there was danger, and then there was The Leap: Swifty taking little Munka (well, their names were not yet Swifty and not yet Munka) in her teeth and leaping up into Mom’s storage unit above her parking space, five feet off the ground. This is how Mom managed to corral them, take them in, take them home. Of course Mom did her best to socialize them as she always did with her rescues. She fed and talked to them, pet them, played with them. Except Swifty just never took to this, even as days stretched into months, and months into years. In spite of all of Mom’s efforts, Swifty still preferred to stay away.

So, fine. Mom gave Swifty her space. In fact, she gave her that entire room, rent-free, for ten years. She gave her room service, breakfast and dinner there, and water, and her own litter. When a meal was extra fancy, like the soft food with gravy Swifty so loved, Mom would shut the door to make sure she could enjoy it in peace, because the others — Snowy especially — liked to come in and take advantage of Swifty’s timidity, and bon appétit.

Swifty also took delivery of a comfy armchair. And a bed. There were also toys and her own stereo, from which Mom would play a bit of classical music every day. (“I’m telling you, she loves it.”)

Swifty got a perch at the window to look out of, and a heater in winter, but Mom would monitor the temperature day and night always, and open or shut the window accordingly, comfort and good air paramount.

What did Swifty ever give Mom in return? Not much, really. But Good with a capital G is a good that asks for nothing back. Good with a capital G was also Gajewska, who was happy to give this quiet spare room this purpose, for this other of her “sweetie pies”, as she liked to call them.

Of course Swifty had run of the house if she wanted, but rarely did she. When she did leave the room, it was usually to chase slants of sunlight as they crept across from one side of the apartment to the other, to Mom’s bedroom. Swifty would follow these slants, sit in them, soak in them, so long as she could do this at a certain distance away from others. Never did she go downstairs. But one surprise did happen, right towards the end: when Mom began to weaken, Swifty would on some days creep in to Mom’s room when we were both there watching a movie, and she would watch us. Sometimes she would even hop up on the other chair to do this while lying down — but never to sleep, her eyes always open, always ready to run. When Swifty did this, when she joined us, Mom and I would look at each other and smile, and we would try not to move or say anything. We did our best just to hold these moments, hold Swifty there as long as we could with quiet, with stillness.

Sometimes good is also this. It’s stillness.

~

Good, then, were the people who liked or shared a post I put to social media, after Mom passed away. It was a post about Swifty, on a page for cat lovers in Los Angeles. It included a photo of her, and her story, and her new plight: where to go now? What to do? Who else, possibly, could take on a cat such as this one? I made calls, sent various messages to groups and rescues, but these went nowhere.

But then, almost as fast as Swifty, that post on social media began to run. It was shared, reposted, liked — all of the things. Then a message popped into my mailbox, from a woman named Elisa. She explained that she and her boyfriend Kevin had essentially made their new home into a sanctuary for pets like Swifty: animals with little chance anywhere else. In fact, their house was full enough of such animals that they agreed to take in no more for awhile. But then she saw the post, and then she apparently told Kevin, “I know what we said, but just read this, and tell me if you think this cat is meant to be here.” He read it. And Swifty was meant to be there.

Going there and meeting them, and seeing their home, their setup… and meeting their dog, who had almost no use of his back legs but still furiously licked and loved when he met me, a stranger… and seeing how Elisa spoke to a terrified Swifty down there in her crate (getting her into that crate was the real miracle)… and hearing about the system they had in place to take in and acclimate frightened souls… and seeing the room that would be Swifty’s — a master bedroom flooded with light, with huge windows that looked out to a tree-filled backyard and hillside, and with an attached “catio” there professionally built and accessible through a kitty door… All of this, it was overwhelming. These people existed, there in this beautiful neighborhood pushed up against those hills, just quietly. They wanted no money or attention. They wanted only to help. And:

What we do stems out of grief, by the way. I wanted to share that with you. Grief changes you for better or worse.

Elisa texted me this subsequently, in the midst of sending updates about Swifty. She explained that she and her partner began helping or taking in helpless street cats after the loss of their own pets — which is also what Mom did, after Rocky. It didn’t fill the void, she said, but it helped. It doesn’t take their place but it gives us a reason to get up in the morning and has given us purpose… And day by day that grief becomes a part of you in a less sad way, in a more connected present way …

Elisa, who has a small tattoo of her cat on her arm, keeps sending me the updates. Pictures. Swifty is doing so well. She’s been upgraded to a room much nicer than than her old one, in fact a nicer room than any I’ve ever lived in myself. And still she’s getting her room service.

In her texts and updates, Elisa also keeps thanking me. She and Kevin, she said, are so happy to have Swifty there. And I must repeat this: she — keeps thanking — me.

Good is quiet, and good is this couple that lives on the east side of the City of Angels, on a street named — and Mom would love this also — Museum Drive.

~

Side story:

As I neared their home, with Swifty in the back of my car, I stopped at a red light, waiting to turn onto Eagle Rock. This was a street Mom lived on when she first got to L.A. She told of this, of how she and Rocky stayed in a rented room with a view of a gas station. As I sat there, waiting for the light to turn, I eyed the gas station on the corner, and some apartment windows there behind it. Was this the gas station? Could that have been her window? I didn’t know. But only then, as I wondered, did I notice the shape of the bushes.

~

Good is Hannah, a hospice nurse. In fact, Hannah was the first person to come see us once Mom was out of the hospital. She sat with us, listened to us, explained to us everything.

Good was how she effortlessly turned away Mom’s worry about the “mess” in the apartment, telling her, “Don’t worry about anything, I’m only here for you.” Good is how she laughed at Snowy’s snoring — he was on the bed next to Mom, and in the midst of this conversation of life and death and pain management and how it might all look, might feel — Mom was asking these questions — Snowy only snored. Somehow this helped. It gave us all a necessary laugh.

And later? Later when I walked Hannah out to her car, wanting to ask a few more questions in private, she asked me: but how are you doing, emphasizing the you. Good was all of this. All of her. It was just so evident from the moment I saw her, but in time Hannah became like family: she checked in on us even when she couldn’t be there; she always answered all of our questions; she changed the medicines when they weren’t working; she brought Snowy treats; she showed Mom pictures of her beautiful family, and Mom became enamored with stories of Hannah’s daughter Emory — like how Emory had a weekly habit of spinning a globe with her mom, and wherever her finger landed, they would then learn of that place, read of the people there, try to make a meal from there. Mom just loved this idea, and began to ask about Emory all the time, and the places they visited, and one day Mom made a little treasure chest Hannah could take home, full of little gifts for her kids — dolls, a spinning top, and books and mementos from Poland, like the traditional vest my mom’s grandmother had sewn for her when she was a child, for whenever Emory’s little finger might one day land on Poland.

This all happened in the course of two months, but still on that first day, when I walked out with Hannah after that initial meeting, it was merely an afterthought that came to mind after we said goodbye, but I turned back. I said, “Oh, sorry, just one more thing, and this is completely unrelated and random. But any good person I’m running into, I will be asking them if they or anyone they know might be interested in adopting a cat one day, as my mom has a housefull, and there will be a time—”

“I would take Snowy,” Hannah said, and I stood there. I said Wait. Wait what? “He’s so cute,” she said. “Listen, I need to talk to my husband about it, but I think I could convince him…”

I stood there and began crying. This was all just starting, and I was trying to hold on, just bracing for what was to come. But there, there at the very beginning of it was this person, this kind of good standing there. I didn’t know what to say. So I said, “Can I give you a hug?”

Snowy had only snored back there on Mom’s bed, yet this had charmed her. Such is Snowy’s power. Such is Snowy’s charm.

~

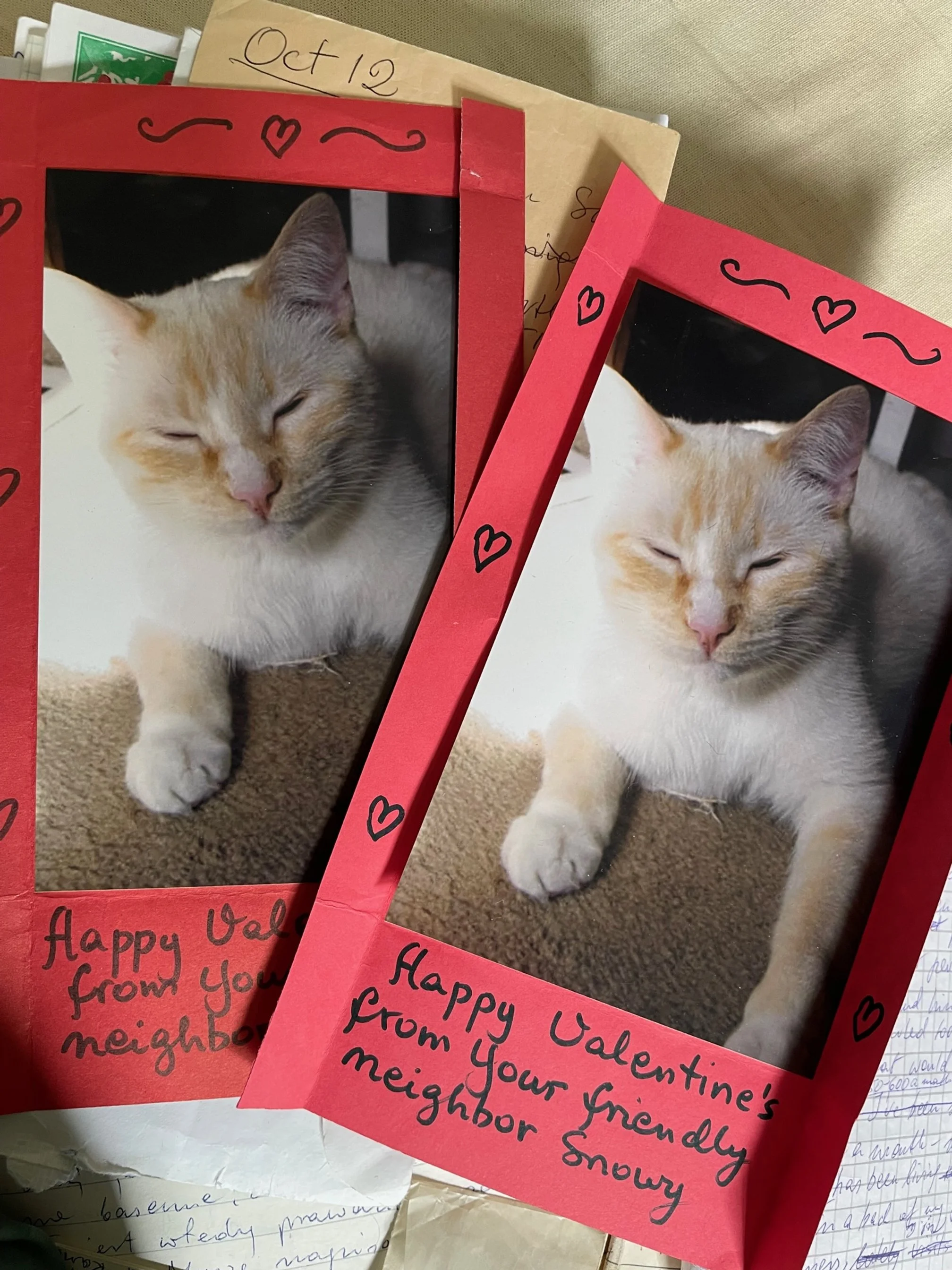

Good is handing out Valentine’s Day cards like these to your neighbors …

Or writing out a seven-page instruction booklet for the person taking care of your cats when you go out of town. …

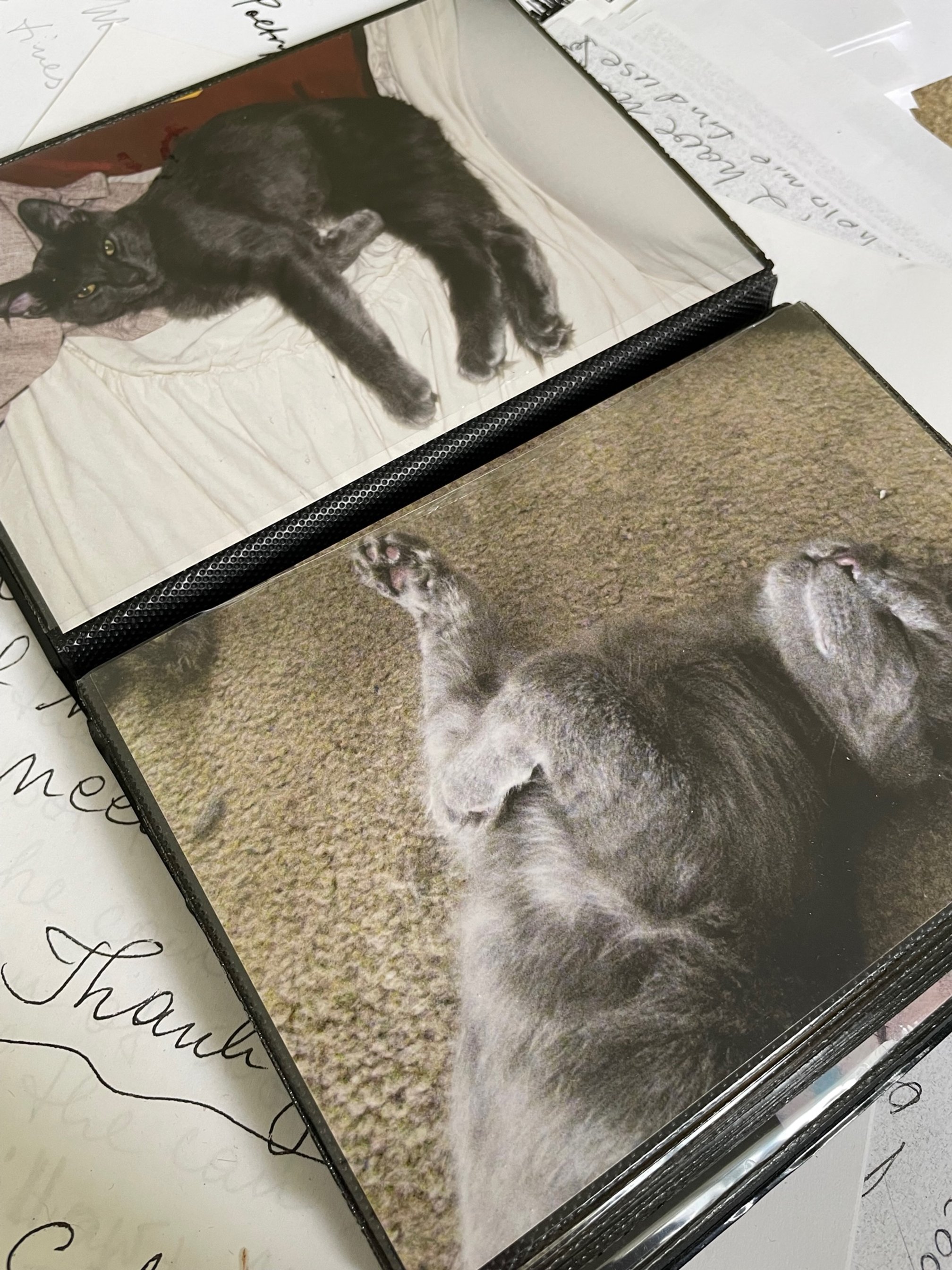

Good is keeping a photo album of Fillow’s baby pictures.

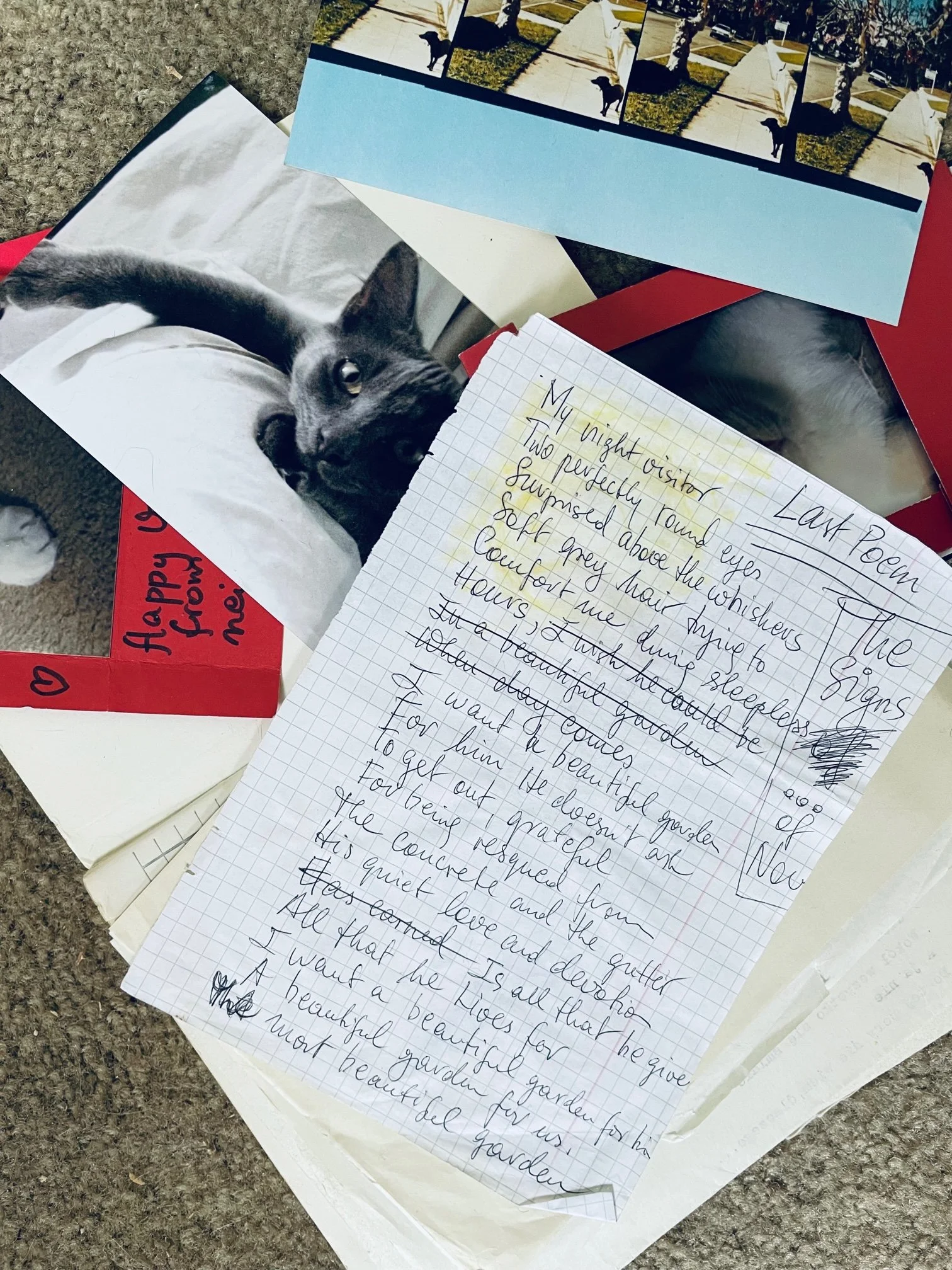

And good is this, possibly Mom’s Last Poem, as it says there on the paper. About

Fillow:

My night visitor

Two perfectly round eyes

Surprised above the whiskers

Soft grey hair trying to

Comfort me during sleepless

Hours

I want a beautiful garden

For him. He doesn’t ask

To get out, grateful

For being rescued from

The concrete and the gutter

His quiet love and devotion

Is all that he gives

All that he lives for

I want a beautiful garden for him

A beautiful garden for us

The most beautiful garden

~

Good is Dr. Leana Galdjian, or “Dr. G” as I heard her being called, at the Granada Veterinary Clinic. Good is how gently she always took a terrified Fillow from his crate, how she would cup his head in her hand, and say always, “Hello, gorgeous” as she looked at his swollen yellow eye. Good is how she felt the bump, the tumor there on his head, and explained to me the reality and the options. Good is how she showed me how to give Fillow the eye drops, and later the oral meds, and how even to shave down his mottled hair to make him cool — all the while telling me, always, to just keep watching him. To “think about quality.” “If he’s eating, and he’s purring, then that’s good. And when it’s time, you’ll know.”

Good is how she handled Fillow — and me — on the awful day, when it was time. How she let me be in the room with him, hold him, then stay with him for as long as I needed. Good is how the clinic put a candle out in the reception area, and a sign for others to try to stay quiet, because someone was in the midst of saying goodbye.

Good was the receptionist, always, and the doctor’s assistant who came up to me after, and said what I’d once said to Hannah: Can I give you a hug?

Good, sometimes, is just a hug.

Or the condolence card they sent.

Or just all of it — all of the work these incredible people do, every day. I can’t imagine it, the pain that comes with the helping. But there, there in that little clinic almost invisible against the loud and bustling 118 Freeway it’s pushed up against, are these other angels in this city of them. And I am forever thankful.

~

Good are the simple kindnesses or interactions of everyday, small or large, we may encounter. Mom wrote a collection of poems about such moments, which she called My America Now. About this collection, she wrote that her own freedom always rested “in the hands of strangers who helped me.” One of these poems was called A Man from a Burger Place.

By the Burger Place / On Washington Boulevard / My car got overheated / All sweaty — I went / inside / Two guys, a bit shabby looking / Offered me a ride / I was about to say ok / I was so worn out / The owner of the place / Took his apron off / Closed his Burger Place / Even though he must have had / Some burgers on a grill / Took me to his mechanic across the street / Waited, after one hour my car was all fixed / He hurried back to his burger place / I came to say thank you / He even paid my bill / Be careful next time — that’s all he said / I think about him ‘til today

~

Good is Gloria, a home health aid with hospice, who came one day to give Mom, by then bedbound, a little bath, and who then said, “Listen, I live five minutes away, so I can always come if you need me. Just write, and I will come. Not for work. I mean, just because I’m here, because we’re neighbors, and neighbors should always help each other.”

There again, I cried. There again I was telling a stranger whom I’d only just met that, you know, in all of this, the one thing so beautiful about these days has been getting to meet people like her. Mom, then barely speaking, nodded, said mm-hmm.

~

And good is Munka. The quiet one. The flower pot. The last of the little ones left.

Good is how Munka tried to hide her worry by hiding under the bed downstairs when Mom got worse. Or how when she did want to come upstairs to check, she would stop halfway up the stairs (and she never did this before) and meow up: was it OK? Only after I called out, “It’s OK, Munka, it’s OK,” or made a sound with my tongue, did she come.

Good is the love and the care we can give to animals, and good is the love and the care they can give to us. With Mom gone, then Swifty, then Snowy, then my brother — it was Munka still with me, always at my side. She saved me. She made me laugh when I needed it. Let me sleep when I needed it. Sat by me for a “think” when we both needed it.

Munka watched me cry. Watched me write. I fell in love with her there next to me, and her little ways.

Then it became time to do right by her, too. Not wanting to put her skittishness, her sensitivity through what’s still to come — a multiple-day journey in a moving van for Mom’s paintings, or the terror of an international flight spent in some cargo hold, or the general oddity of my life… And with Hannah there, saying she would take Munka also, that Munka could have her own room to transition in as she needed, and that she would get all the love in the world that she needed…

It was time. After several days, finally I managed to trick Munka into the last crate. This was Sunday, a most painful Sunday for us both, and by Thursday I had been back there twice, visiting Munka in her new place, apologizing to her, telling her it would be OK. She’s still scared, still transitioning, still unsure of the new noises, new smells, unlike Snowy who is now so happy, so home there — running up and down the stairs after the children, or cuddling with his new sister Emory at night, and maybe somewhere, maybe in a garden with Fillow, Mom is smiling.

But Munka, Munka is still worried. She even stopped eating for two days, so last night I went there yet again, and out she came from behind a TV, came and sat next to me. We had a “think”and a cuddle, like we used to. And she purred, like she used to. Twisted her head around and placed it on my shoulder, like she used to. And then she ate.

We hope Munka is home, just as Snowy is home, as Swifty is now home. We hope this is just a rough patch for an especially sensitive soul, but we will see. If not, if in time she still struggles, well then we will figure it out, will do right by her, and I will come get her. Because we must. We must do right by the creatures who need us, who help us along, and do as Mom always said: “Look to animals, they will show you the way.”

Mom always did what she could. Not just with her cats, or with Rocky. I’ll remember forever how when her former neighbors kept their dog Brody out on their patio when they left for work, Mom hated this, found it so unkind, and was so pained by Brody’s bark that she argued with those people. And then, when still they left the dog out under that pitched tarp while away, Mom would go out to her own patio and talk to Brody through the wall. She would tell him it’s OK, and would play music for him, too.

And Brody’s bark would quiet.

Mom also helped to cure the feral cat fiasco around here years ago, catching, fixing, and releasing several cats she couldn’t take in herself.

And Mom was that person at Central Park to go right up to a resting horse, one of those poor souls made to haul a carriage all day in the heat, and she would hold its nose, would look into that horse’s eyes, would whisper to it. I will remember this, too.

This kind of good was Mom. But this kind of good is so many others.

This kind of good is probably you. Or can be.

So let us guard this good, keep it close, remind ourselves of it when things get loud, get annoying, get dark.

When I left Hannah’s home last night, left Munka hopefully feeling better and a little less scared, and made the 30-minute drive back from Simi Valley through those rocky passes, the outline of some low mountains formed in the distance, in the halo of the L.A. lights there behind. I did something illegal then — I reached for my phone, and tried to capture this.

Because I found it to be apt, this picture I was driving into. I thought: this is like the light I’m coming from, that wonderful family back there on that quiet cul-de-sac. I thought: this is like the good that exists beyond so many doors, the doors we do or don’t open, or behind these mountains we must sometimes travers. Always somewhere, somewhere behind us or still ahead, there is light, there is good. Good is the good that lives there, just like that. The good we rarely see or hear about, or get to touch. But it’s there. There always. Even if it’s quiet, it’s there.