Mom’s books, and the pain of losing

Later I moved to the San Fernando Valley and drove to my work in Pasadena. I lived in a very nice area, in the hills. This was a time when I started writing poetry on a regular basis, most of it conceived in my head as I drove back and forth to Pasadena.

~

Yellow flowers, like bells

Two assistants, I,

six autistic kids

severe cases

Hard to handle

The goal for today

Community walk

Through the neighborhood

Nice, quiet neighborhood

We are streaming through

like an unnerving, neurotic river

of sounds and

uncoordinated movements

Sometimes we have to stop

to tame behaviors

Then, we’re moving along

again

Like a river

When the river’s bursting

We stop

We stop

by the tree with

Yellow flowers

like bells

Michael needs something

To calm him down

So we rush

To pick the flower

We put it in Michael’s hands

He is focusing

He is looking at it

for a moment

He doesn’t look all around

His hands still

go ahead, Michael,

smell it, feel it

it looks like a bell

unique flower

he looks the other way

a little calmer

A lady comes out

It is her house and her tree

Bells are ringing

Strange river by her tree

Unique tree

with unique flowers

two yellow shapes torn

on the ground

What she is going to say?

What she is going to do?

She is looking at us

Trying to understand

The bells are ringing

And it is all quiet

when she kindly - smiles

~

“Diamonds”, oil on linen

~

I was painting too, my paintings were pastel, I painted to music thinking that I should concentrate on just that. I imagined life without any problems and me — painting just music.

Debussy

I long for the waterfalls

Clair de Lune

a melody I heard

between

parking lot and street

Long for the music

Transition of

dimensions

Play it now

Starved for the

reflections on a

water surface

underneath the water

stream all over me

for me

shattered

in broken

dimensions

play Debussy

Debussy, oil on canvas

Music, oil on canvas

~

Mom was substitute teaching now on a regular basis. It went like this: she would get a call in the evening or extremely early in the morning from an electronic messaging service. The service would list the job available, the school, the amount of days required, and she would press 1 to accept, 2 to decline, but Mom was always pressing 1. She needed survival. Rocky needed survival.

That place she moved to in the San Fernando Valley, in a very nice area, in the hills as she wrote, this was a room she rented in a lovely house, offered to her by a Polish man, friend of a friend she’d once met at a New Year’s Eve party. At first she’d declined his offer, saying it would be too far from her teaching jobs in Pasadena. But later when she was about to be homeless again, was given two weeks to find a new place, she called and agreed to rent the room until she could find a place back in Pasadena, to stay close to work.

These details, all filled in here by her other book, the one with Rocky.

I remember the house. I visited Mom and Rocky there during a summer break from university, driving out from Texas. There was a pool. There were spruce trees. And rolling brown hills in the distance. Comfort. It was so nice to find them there, my Mom and my dog, in a place like that. They were both wagging their tail.

Perhaps not so surprisingly — because Mom was, is, beautiful, and because men are predictable — Jerzy the businessman, who owned that home, eventually tried to get closer to Mom, maybe it was his plan all along, and eventually succeeded. They began dating. He picked her flowers from his garden and she loved this. After awhile, she even thought she loved him.

Times were good. The poetry and paint flowed, but especially the poetry. She would think of ideas, verses, while driving to and from those teaching jobs back in Pasadena, a trek along the 210 Freeway that rose and fell like the sea, that wove through more hills and offered a view of distant mountains. Of course it was still L.A., so there was always traffic. Eventually she managed to transfer her substitute teaching jobs to schools in the Valley, releasing her from those longer drives.

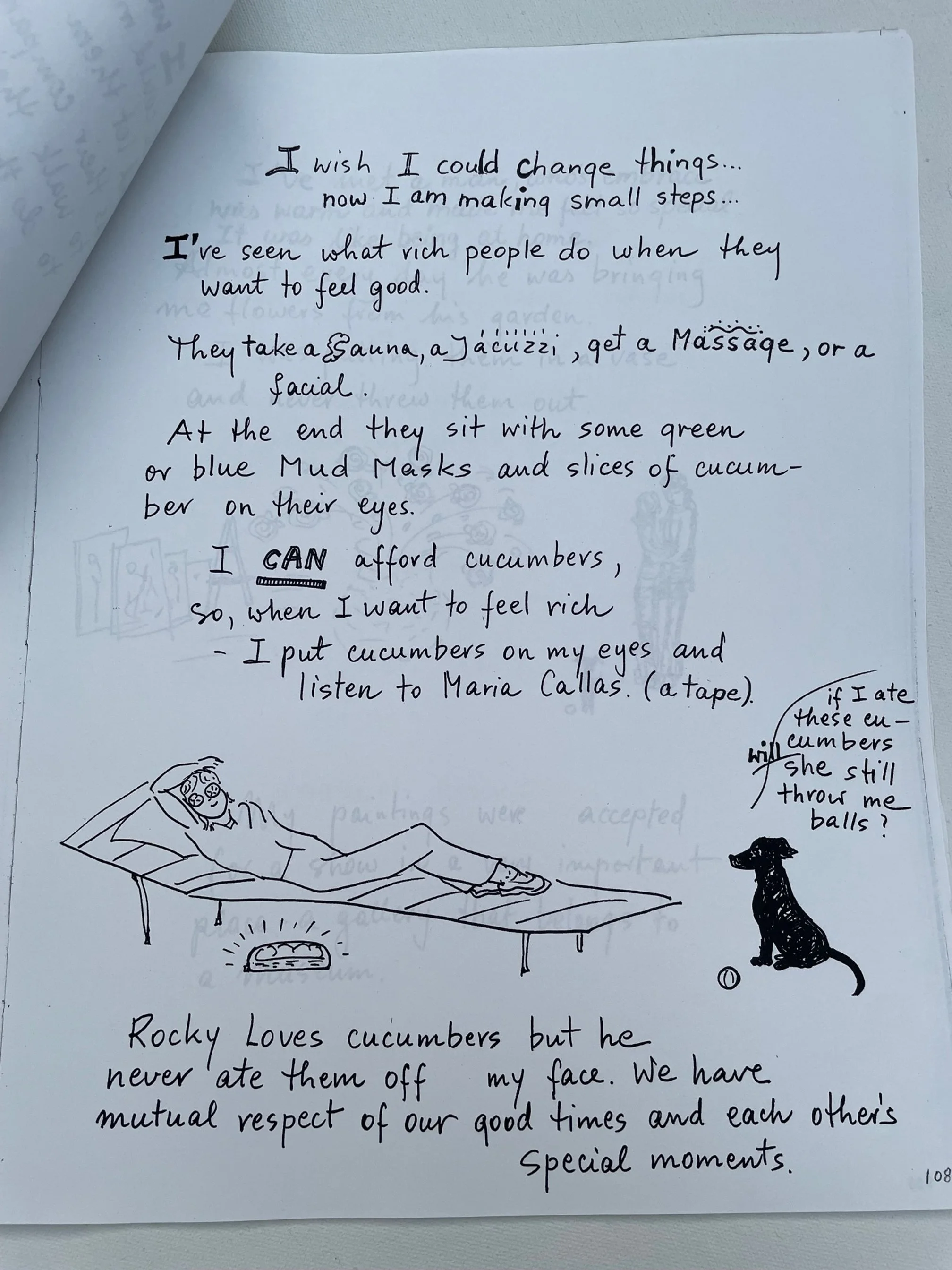

Was she happy? Really she thought so. At the very least, she was actually beginning to feel somewhat secure. Secure for the first time in — forever? At the end of her work days sometimes, she would even allow herself to take a rest from the painting and poetry and just enjoy life, some lounging with Rocky out by that pool. She would play music from a cassette player and put cucumbers over her eyes because she’d seen that rich people seemed to enjoy this. Rocky would come over and drop his ball by her hand, and she would feel around for it and take it, toss it, and he would fetch it, bring it, drop it again. (And even though he loved cucumbers, he respected her tranquility enough to not lick them them her face — but still, here’s the ball…)

The salesman.

That summer visit.

The cucumbers.

~

Was she happy? Yes she thought so, even though there were “some issues.” So she said yes when Jerzy asked her to marry him. Mom told me this part of the story only days ago — yes, he did propose (I’d never known this). And yes, she did say yes. Even though there were still those “issues”, and even though it bothered him so much that while she’d been divorced legally, she hadn’t gotten some official annulment of her prior marriage from the Catholic Church — he was a devout Catholic, and this was very important to him; she was religious, but no longer denominational. But for him, she was trying.

And then the rip.

On what was supposed to be such an important, beautiful night for her — Mom’s paintings had been taken on by a gallery, and here was the Opening Night — the rip happened over a single word: “Darling.” See, Mom’s L.A. friends had all shown up in support, and among them was Randy, a quirky lawyer she’d dated only briefly before they agreed to be friends, and a true friend he did remain. Jerzy knew this. But when Randy arrived that night and uttered the playful name he often still used for her, almost as a joke — “Hello, Darling” — Jerzy couldn’t handle it, lost his temper. Couldn’t forgive it. Mom, startled — though she had been somewhat on guard due to some other red flags of personality — said OK. Fair enough. Perhaps she hadn’t even made public their little engagement back then — to her friends, or even to me — because she’d always had a premonition something like this would happen. Another Too-good-to-be-true.

So with Rocky, she was back to looking for a place to live. Had she really been in love? Or was it just the security of it? Of that home to go back to, of her and Rocky being able to sit by that pool and those hills? These were the questions which rolled around in her mind as she scrambled again for a place to live, and wondered what exactly she was losing. When she rented a truck to move her paintings over to a storage area, and carry herself and her dog away from that home and towards some next chapter, Jerzy made a point of sitting there in the lovely home while it was happening, and not helping her carry a thing. This is when she knew.

So in that truck, headed away from that pool, that cucumber life, she could still be heartbroken but she could also know she’d avoided a mistake.

And beside her, panting in the passenger’s seat anyway, was the real love of her life.

~

I moved two more times until I settled in one place. I felt peace inside. Now I could concentrate on my work for the first time, after so many years of being in transition.

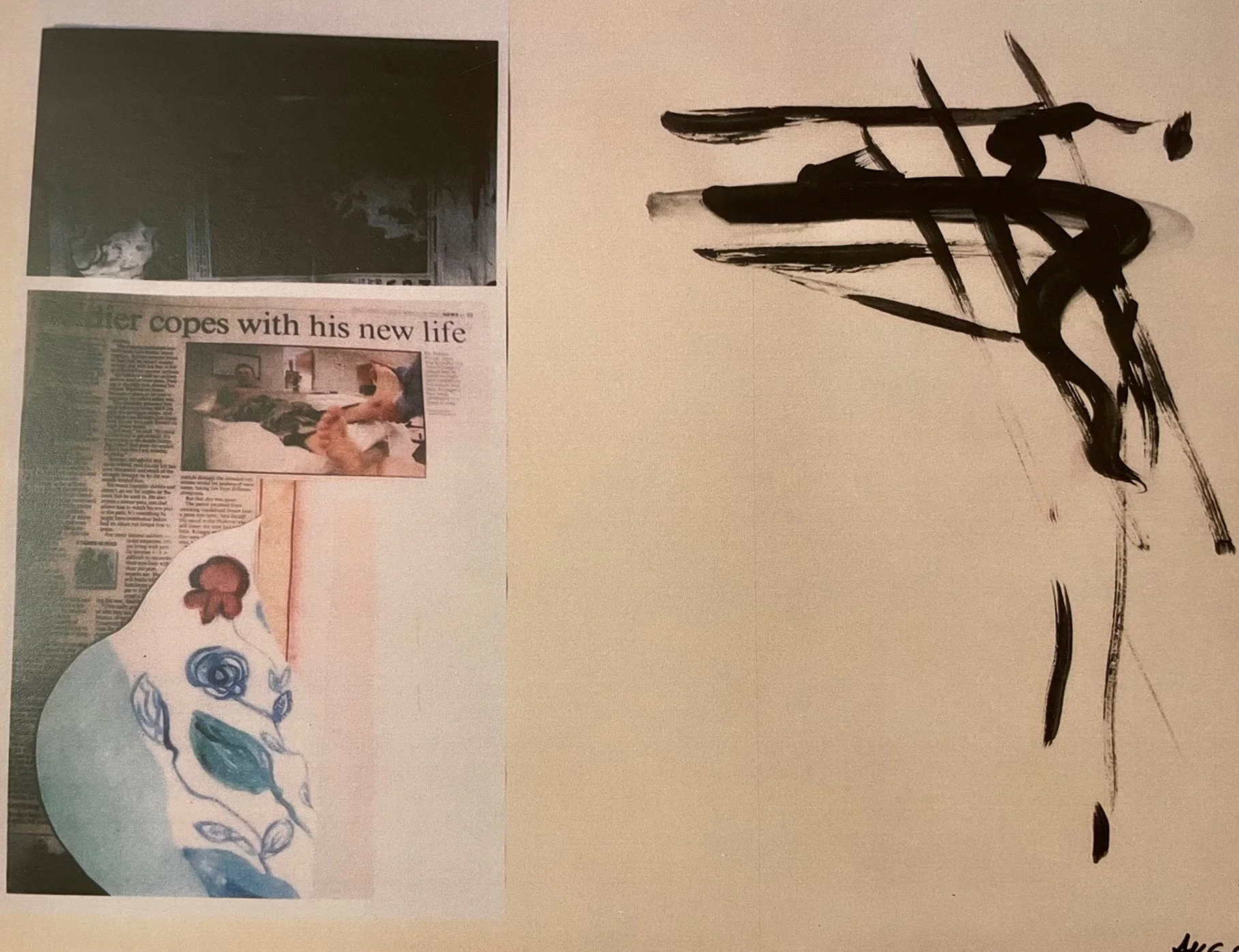

I went to Poland for my dad’s funeral. We were all in mourning three days later when we got news that thousands of people perished in the attack on the Twin Towers. The American Embassy in Warsaw turned into a bouquet of flowers. I was glad to come back to the West Coast, but I felt the world had changed.

Love 9/11

Piece by piece

By the whole Nation

Made perfect

Connected enormous

Blocks of steel

By the Nation proudly erected

The Monument to Human Skill

Carefully built by common effort

Not one worker during that process died

It was Ahead of Its Time Structure

A Monument to Human Mind

One day someone danced

On a wire connected to buildings

Sea eagle flew close to watch

And people observed with wide-open eyes

As control over fear went on with its task

Beautifully, effortlessly

That day when the two towers

Fell to the ground

The thousands perished

The thousands survived

Thanks to those who came rushing

To that Tower of Human Love

Steal workers came to cut steel

In a quiet process, piece by piece

Separating flesh from the steel

Tears on that broken

Skeleton of debris

The buses didn’t charge fare

We cared for each other, we embraced

In that Temple of Human Despair

Those ashes are still in hearts

The ground with its emptiness cries

That day when two towers feel down

Something stirred in our souls and minds

And stays

As high as that man on a wire it stays

I was supposed to relax now and concentrate on my art, I was supposed to paint to music, but instead I was writing.

I wanted to preserve memories of my Father now that he was gone. He was always dreaming of going to America. America always meant “Peace and Freedom” to him.

He made me love that distant country a long time ago.

I wanted to write prose that would read like a poem …

~

Once I was a girl,

living in Poland by the River Visla

walking with my dad, holding his warm hand

and dreaming

It was 1959

It was fourteen years after the end of World War II,

when Warsaw was still covered with ashes.

No, in reality it was just plenty of dust since the banks of

the river were not covered yet by the grey concrete.

That came later, progressively, with communism

establishing itself as the gray concrete or magma,

a phenomenon felt painfully by my father.

It had nothing to do with me.

I had no recollection of any war.

I had no understanding of how my father felt,

He would never tell me, because I was just a little girl,

who just went to preschool and had plenty of problems of her own.

I was finding little treasures on the ground,

some pretty pieces of glass and I wondered

where the other pieces were.

I found comfort in my father’s presence

not just because he was my dad.

He was telling me how beautiful the voice of Billy Holliday was.

He was listening to Johnny Cash and Dean Martin.

He had a few records like this.

My mother’s family was surrounded with objects reminding them

of the “Lost Past”. Talking about these objects brought comfort to them.

My Father’s quiet sadness knew no discomfort in such things. His comfort was

in longing for some other land, some other reality.

He was suffocating in his own reality, broken down.

I preferred to be with my Father. I didn’t want to see

what was lost, and what was still holding some value.

The objects salvaged seemed to be connected with the pain of losing.

I wanted to create reality on my own,

reality of more abstract value.

The sparkling pieces of glass, found by accident,

(some had wires in their structure), were full of mystery and were

telling me stories I could half imagine.

With those little glass pieces in my pocket, listening to my father

telling me about Billy Holliday, or about Johnny Cash,

I was escaping to a different world and I was glad that my father

was taking me there.

My world was just beginning. And there was so much to learn

~

9:06 p.m. now. On a Sunday in August. We’re in her final home, where at last she settled, her own name on the rental agreement after two more rooms in two other houses. She’s been here twenty years.

Here, in a neighborhood that’s not so cucumber. Here, in an apartment that’s still cluttered (Mom remained that girl who collected shiny things, her treasures and half-stories).

Here, where now we deal with the pain of losing.

Losing taste, losing appetite. Losing balance. Losing Fillow.

Losing each other, losing this. Losing here.

We’re upstairs in her bedroom now — probably she won’t go downstairs again, will never sit on her patio or watch Columbo or Little House on the Prairie, her favorites, on that TV again.

The oxygen has come into use. It’s up here now.

An IV is also being tried tonight to help her with fluids, and between these sentences I’m keeping an eye on the drip.

Suddenly she wants no bubbly, no Brooklyn, and no more of the beets — those will stay downstairs also, in the refrigerator, unfinished along with other things she eagerly asked for only a moment ago. Now, it’s mostly No.

I play Debussy. And this she does like, but only for a little while, about ten minutes, and then No.

Yesterday she said, with earnest, “These have been the best two months of my life.”

Today she said, “The party’s over.” Now, more of the pain. For that we have the morphine, the Oxy.

But what to do with the pain of losing? If only there were a place to put it. If only we could do as she did as a girl, with those pieces of found glass — she would take them from her pocket and place them in a box under her bed, close the lid, and only look at them again when she wished.

If only.

Here, no such place for the glass. So we put it here, into pieces.