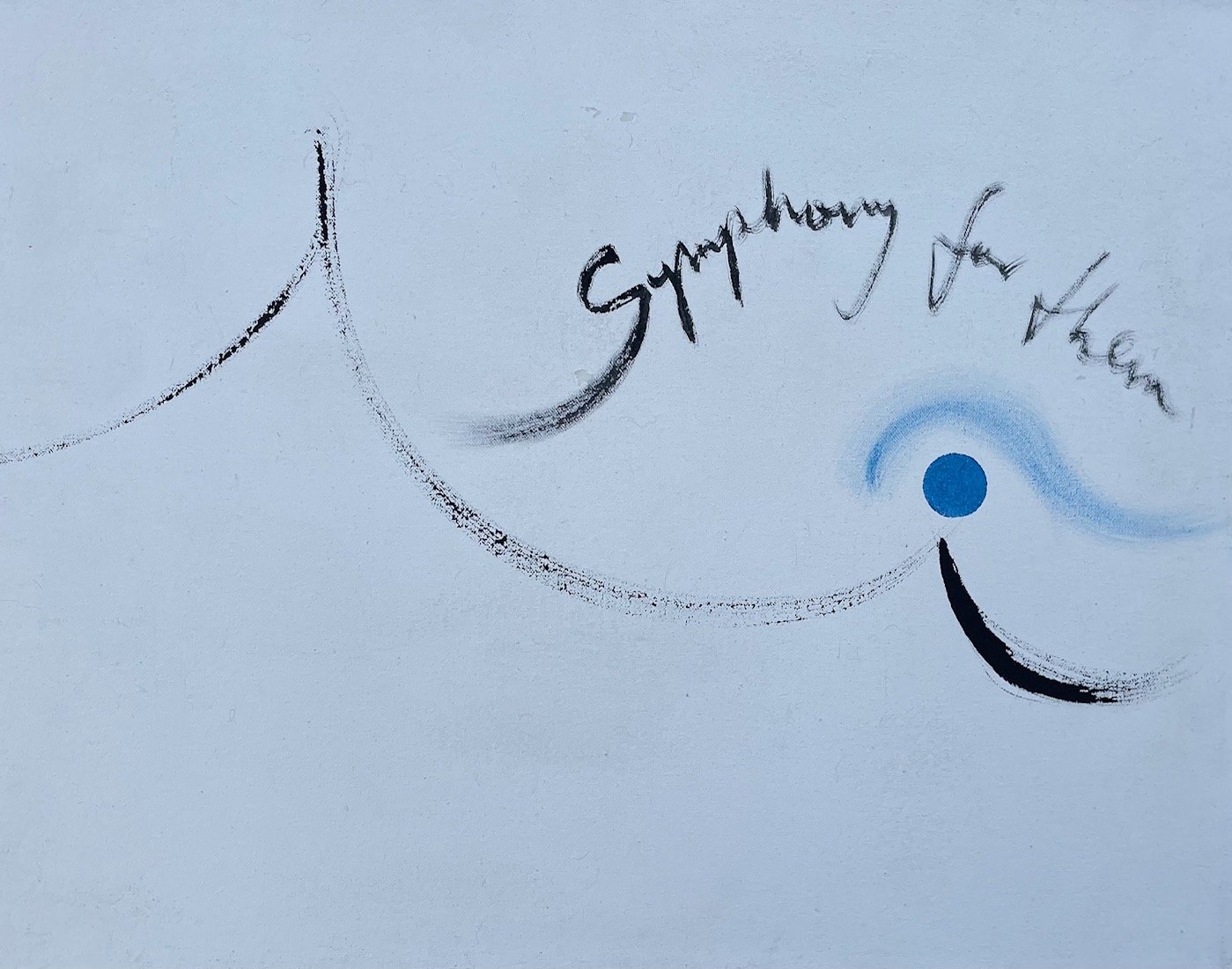

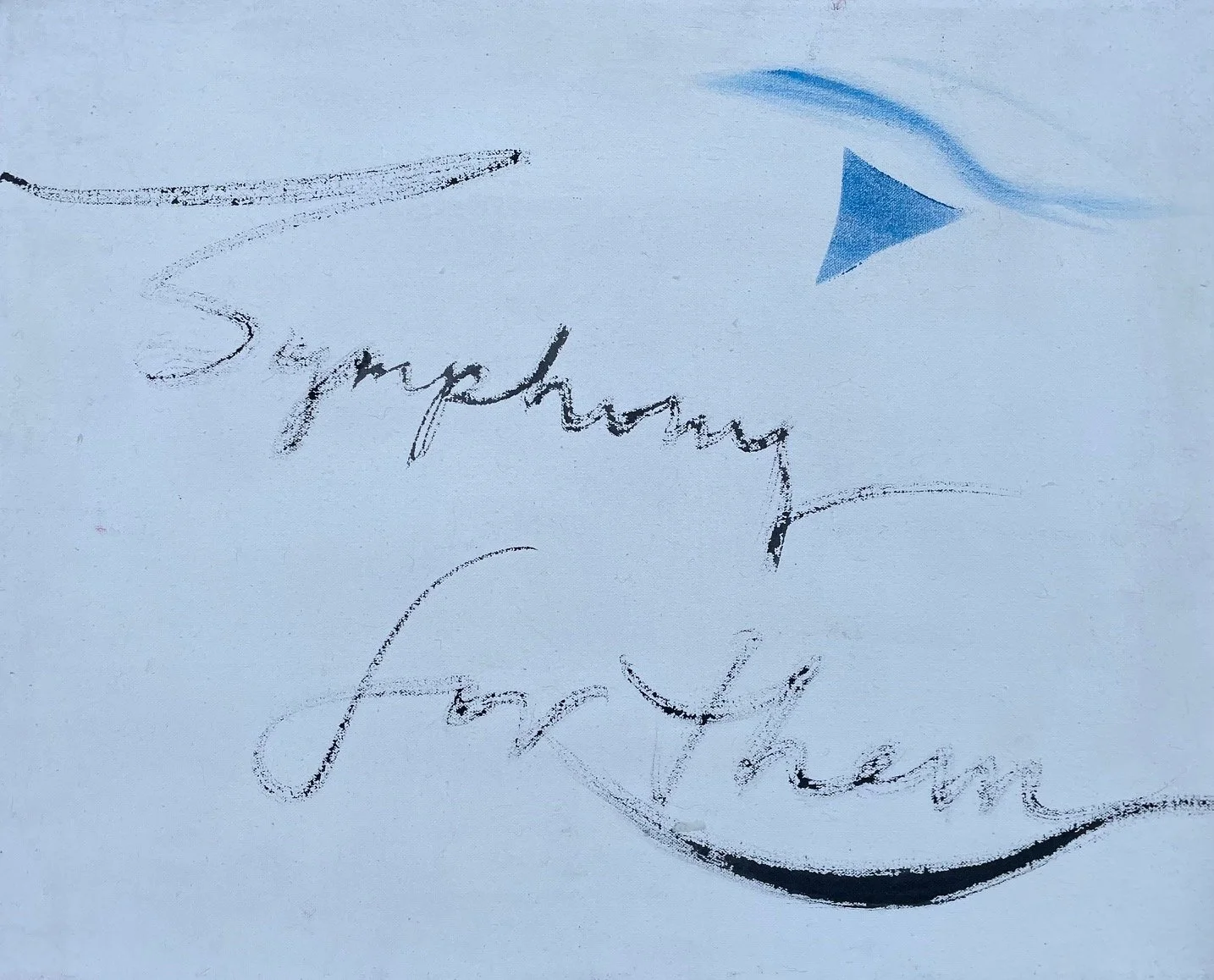

Colors, shapes

Because you’re asking me if I want to paint something. So I’m saying that I would like to.

The press of a button, the triangle there. And she’s here, she’s out of the silence. I can hear her, and you can hear her. And these are the fragments of her voice we still have. This one, from twenty-three days before she took her last breath.

… Have all of these forms. Cutouts. You know? Cutouts, forms. Floating in the air, very nice and happy and colorful and just simple, you know? And uh… Like I give example, right? I give example of some things, some simple design. Not overworked design. Because, you see, cutouts were always very good for me, because I had a problem with oils. I had a problem with oils. Because oil is very slow. It’s like – it’s like mushy, very slow, right? But you get the best colors with oils. Now, there is acrylic paint. Not such great colors but very fluidity. You can, you can – splash. You can splash, which is better for my art. Splashing, something like — I don’t over work, I don’t overthink when I have this kind of painting, right? With oils sometimes I overthink.

So, um… But I discovered at some point the best, the best possible technique for me. And this is, this painting that Jan Kott bought from me, because it reminded him of Japanese art – so I had this white canvas, it’s the one in the museum (in Torun). Yeah, white canvas, and rectangles. Like, red rectangles, small ones, right? And then, some ink and some pencil, right? That’s it. It was a great painting.

So I’m thinking, this is amazing. And another – another … I have another Japanese painting, it’s called The Sounds of the Desert, and to me it’s, I think it’s my favorite. Sounds of the Desert. And it is very similar thing. A very similar thing. Like, horizontal things, a lot of white. This is my favorite painting.

Where is that painting?

Oh, I will show you. So, I even bought a brush – a Japanese — no, a Chinese brush, I think it’s Chinese. In some Oriental store, for fifty dollars I bought this brush, and I have this brush, and I was going to paint with ink, and it was going to be a line with ink. A line with ink. On white canvas. Sometimes it could be enough, just that. You know, this is oil, but with ink it’s like — Shfeet — and you have a line. And if you add just any form to it you can. You know? And that would be my thing, because it has a lot of freedom, a lot of… air. You know? Life and everything. And uh, I did not continue this thought, and I did not because I already had too many paintings. So I was already, like, enjoying myself too much. Walking with Rocky and enjoying life in California. So I did not continue this. Because what if I paint these great paintings? But in Heaven I will continue that. It could be jazz, it could be line. Those two things I would continue.

Do you mean you’d mix the lines with cutouts?

Yeah. I would do both.

Two separate things or combined?

I would either do just cutouts, floating in the air. Or lines. And cutouts floating in the air.

When you say cutouts, you mean what exactly — just shapes?

Just shapes.

~

She’ll mention shapes again, here in the next pages of her book. The one we’ll finish now, at last. And I’ll find mounds of shapes after she’s gone, upstairs in the other room — cutouts, fragments. Fragments from other paintings, past canvases. Fragments maybe of failures, which could be made now into other somethings.

And I’m wondering when I look at them: which of these could be the shape of living, and which of these could be the shape of dying? Which of these could I put on a canvas and say This, this is light? And which of these would I take and say This, this is grief?

~

Her book now, her next pages…

Promenade

My dog simplifies my life / With ideas like: / tennis ball - yellow, round / Black ears - sticking out / like antennas / May I have a bite / of what you are having? / he waits in hope / for a good moment / licks my face / Let’s go on the promenade / wind blows / problems like / flea powder / sprinkled behind / a tail’s making circles / in the air / ears flopping make / helicopter sounds / I follow / Let’s go!

(And a photo of the Santa Monica Promenade, found also upstairs, in her collection.)

I love nature. In time of peace I would be making art all-nature-like, all-intuitive, contemplating colors, shapes.

I was trying to write articles (which I wished to be published in a paper) about the human race, humanity, bringing normality, talking about values, and about loving our neighbors. Kindness, Values — there is a lot of strength in these words…

Chandelier

Scented candles are not only for Christmas / Love does not happen just one day a year / Imagine the year as three hundred crystals / Making one big and sparkling chandelier

Christmas lights are not only for Christmas / And candles are not just for one religion / Red ruby slippers are not for just Dorothy / Roads are not only to Kansas, but to every region

Beauty is not only in things that are beautiful / Music could be played not only by a pair of strings / Sometimes it plays without sounds / And quiet angels show up on their legs / Instead of their wings

Sometimes a word is as pretty as a light bulb / If you make one word sparkle just a little every day / Then by the end of the year you know that you have created / The crystal dazzler with dazzling crystals chandelier.

~

And to finish, she left another poem, and then a small statement. The poem, called Jazz.

Jazz - the language of wonder

For a moment

getting loose

like a bird

kept in a cage, now

his wings

sprinkled with iridescent blues

Jazz- the city is transformed

To the place that illuminates the moon

You’re less lonely

You’re connected

When you hear that lonely saxophone tune

Jazz against us being different

Although they’re still showing you the back door

But the soul, all glorified in all colors

Makes its way to where we ALL come from

Jazz against the war, on the wings of airplanes, on trains

In the cities of cars dancing to the sounds of horns

If you lost all hope, jazz will come and take you to

where things grow out of ashes, where everything is born

When you died, but want to feel the unexpected

Still coming to you in the white dress and in the white shoes

Forgetting how hard and abrasive was your pavement

How long you had wrestled your fears - suddenly comes the blues

You take an instrument, your past is no longer your future

you are standing all dressed, all alert, clear, all renewed

Sharing how you feel without words, but in the clearest statement

showing off your life as a priceless jewel

Telling them that your soul has such fine capacity

Of capuring textures, raggedy so, that once made you bleed

Now you are standing there, sparkling like an angel, for as long

As your wrist connects your mouth with your heart - you become unreal

Beneath is the city, people are suddenly dancing

there is movement, the bodies, connected like a vine

suddenly all that was sleeping once, is - awakened

Suddenly all that we want and want to feel - is jazz

Someone asked me to make a DVD about my art. When I show my art I always go explaining what I did and when. Yes, maybe I should record, this is a story, this is my diary.

I hope that one day I can go back to contemplating forms and turn it into huge silk screens, I wish I could paint free lines mixed with my cutouts. I would call it “Jazz”.

~

Now the button, the triangle again. Her again.

It looks like, uh, I had a great chance. Before my cancers, you know, I had a whole decade to do this. But I never did. Then I settled down here. I settled down here. I was totally ecstatic about the fact that I will never have to move again. That my job is going well, that I had a job in the summer, and everything is going smoothly. And uh, it was also the time of … also the time when this 9/11 happened.

And Dziadzia died. [her dad]

And I got — I decided that painting doesn’t make sense anymore, like individual. And I was making, like, photos — making photos of April, of Keenan. And I had these lines. But with photos, of real life, because I thought real life is in danger right now, globally. And I was like mentally in another place. Like a philosophical place. And I would never really go. Because I found something really great for large canvas, and I said to myself no more large canvas — it’s like too heavy, too big, I’ve had it with large canvas. So I just, uh… I just abandoned painting.

But at the same time you created that book, for gallery people.

Yes.

So, is that so you could give the paintings that you had already created? You were looking for homes for paintings that you had already done?

What is the date on this book? Is there a date?

I mean the date… I thought you created it sometime in the 2000s, it was like around 2006 or something...

Oh it was?

I thought, but you know, it’s difficult to say because it’s not like, so… a date on it, but you include stuff of April and me. You include stuff you did in 2004, 2005, with myself, with April, with Keenan.

Yes yes yes. And those lines are there. But I didn’t really, like… Yeah, that’s what I was, that’s what I was. It’s just that I never realized that I found my perfect technique, you know?

But Mom, you know you say this at the very end? You say the same thing you’re saying today. At the very end here you say: ‘Someone asked me to make a DVD about my art. When I show art I always go explaining what I did and when. Yes, maybe I should record. This is a story, this is my diary. I hope that one day I can go back to contemplating forms and turn it into huge silk screens. I wish I could paint free lines mixed with my cutouts, I would call it Jazz.”

Yeah. Oh — mixed with lines, I said?

Yeah. ‘Free lines mixed with cutouts.’ So you already wrote your ending, Mom.

Oh, so everything is there! Ahhhhhh! Yeah! So at least it’s good that I wrote this book. At least it’s good that I wrote this.

And as I suggested before, if I were tweaking this — not tweaking it but if I were adding to it, or doing anything, especially if you don’t plan on doing anything much more, I would add the two words at the very end, ‘I wish.’

Yes. Uh huh.

And then it’s a finished — for me that’s a finished story that makes sense. And that’s your story.

Yeah.

But it’s funny — so in the last couple of days when you’ve talked about how you’ve been thinking about how to end your book, it was this.

Oh ok, very good.

So at least you know yourself, and you know that the ending is still the ending.

OK, yes, very good. But you know what…

Yeah, Mom, here it says: “Video ideas sent to Library of Congress, 2006.”

Ah, 2006. But I will show you these two Japanese paintings that are to me the best paintings I ever painted. You see, because I was always — my paintings were always a reaction to what was happening, in a way. Like OK, I went to New York, I painted the Statue. Or I was thinking about… I was painting to music, and very zig-zaggy jazzy paintings. You know. But I wanted to have a style that is unique, mine and is not according to — that I am not absorbing everything from the outside. That I’m just, like, painting what’s inside of me. My own mark, in a way. So…

So you think actually what’s more inside of you is how you describe the end – these lines and these cutouts, that’s what’s inside of you more than these paintings that are around us right now.

More. Yeah.

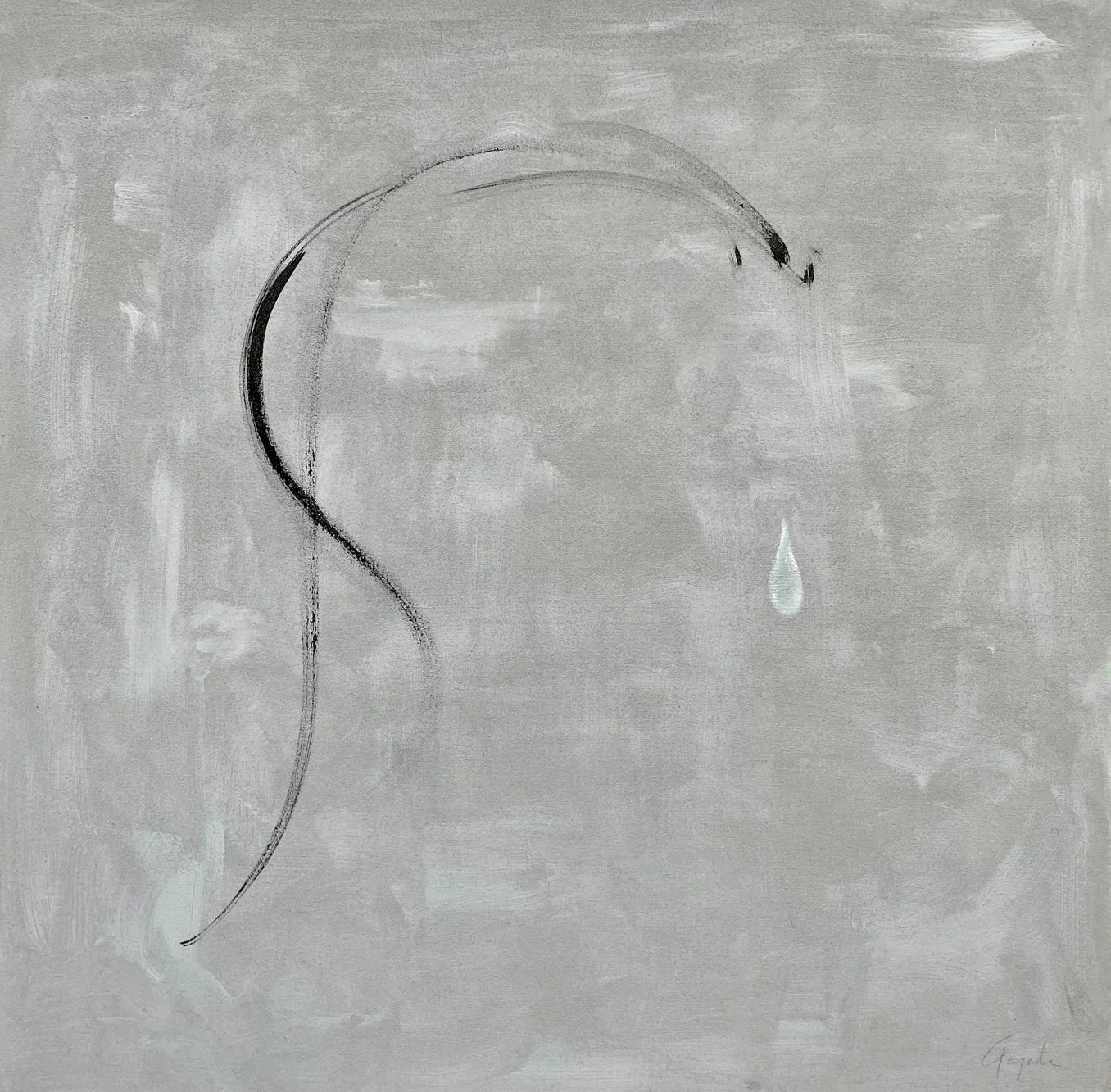

But, would you say that that painting above [I point] is what’s, like, in you? That form? That circle? Line?

That one? Yes. Yeah. Yeah.

You know who just wrote me about how much she loves that painting? Jenni Malone.

Really! And Jenni is very much into Oriental art. Yeah. Yeah I painted this painting and I said to myself, Darn it. Darn it! That’s it! So simple. Line! And it satisfies me! How — how fast it took? It took very fast! Didn’t overpaint and overpaint and overpaint.

Did you do that around the 2000s? Like around that time? No, wait, you have it in here I think — that one comes earlier. [I flip back through the book]

You know, it must have been — maybe Jas, maybe that was the end. Maybe it was my end painting, actually. Maybe it was my end painting.

You have it in your book — you have it early on. But you don’t have a date on it. You know Mom?

No I don’t have a date on it.

You think it came later, but you put it in your book sooner?

No, it doesn’t matter where it is in the book.

You said: ‘Six years before, when my children went to preschool, I started to work part-time at the local community college. I got a divorce in 1989 and moved to a one bedroom apartment with my two boys. I freed my soul but survival was tough. I was hoping gto make extra money I needed with my art. The process of making art is more fascinating to me than art as a final product. To some degree you are in charge of the process but to some extent it is also a total surprise. What makes me paint a line? Is a line in a painting as a musical note is in a symphony?’

Oh!

And you have this painting [in the book, the photo of it]. But you don’t do the year, it just says linear painting, oil on canvas, 40x40.

Oh, you see? No, but it was. No, this was like the last painting. It was when I wasn’t painting anymore. And it was when I was painting these, like… I had these soldiers, the images of soldiers, and it was all very depressed because it was like this distraction. Distraction, distraction. And then, you know, suddenly I painted this. You know, there was no element of… outside element of distraction or anything. And I look at this and said to myself, Oh my God.

~

Listening, there are moments when I cringe. I don’t know why I was so focused on dates. Maybe it’s the journalist in me, wanting to get the facts and order straight. But in Mom’s world, I’m realizing even more now, dates or sequencing doesn’t have such importance, such solidity. One example: after she died I found that she’d written down a list of movies that we’d watched in the span of a few days, maybe a month before — yet she wrote this list down in a 2013 calendar.

Secondly, there are moments in that recorded fragment, and especially in the longer version, when she expresses regret over not having done more. Continued. Not having used the Chinese brush. She even says she got lazy.

But what Mom did already, and what she found — this to me is the important thing, rather than what she didn’t do. Mom did leave a trail of treasures. A life’s worth of paintings. And a study in process. She also raised two boys essentially on her own, in a new country and with English as her second language. She worked survival jobs, settling eventually in California, and into substitute teaching on a daily basis in public schools, working with kids of all kinds, with classes and subjects of all kinds.

Mom was kindness, Mom was values.

And then Mom began to get sick. The cancers. The hernia nightmare and complication. The chills and stomach issues and the thyroid and the bouts of insomnia — earthly problems, but Mom was simply never very healthy, in the last decade or so of her life.

But when she did feel well enough, she enjoyed herself, and deserved this. She traipsed all around her beloved L.A.: trips to the Japanese Garden, to museums (especially the Getty); trips to the Marina, where she rented either a kayak or canoe and paddled out to the ocean (and wrote Boats! in her calendars for this, always with the exclamation point).

And she was writing. Clearly, she kept writing. Poems and prose. Letters, ideas and random thoughts, on any calendar or scrap of paper.

And she was thinking. Forever contemplating forms, shapes. And the colors of existence. Often now I think about something she said ten days before she died: “It’s very abstract, what I’m going through.” She found it difficult to explain much further. Because sometimes words aren’t enough. And increasingly I would find her, as our days dwindled, just lying there, no music, no TV now, no books no sleep. She would just be lying there in a silence, thinking. And I would say Hey, hey Mom, how about a movie? Some music? And she would be saying no, but telling me also not to worry, it was OK.

Maybe she was thinking as an artist until the very end, just going further inside. Maybe there were no more words.

Even I can’t think of what to say now, when someone asks me how’s it going, or how am I. And allegedly, I’m a writer. But words aren’t enough here, they won’t do. Just as I wouldn’t know what to say if someone were to ask, “What is it to be human?”

Maybe the only thing to say anymore is, it’s colors, it’s shapes.

~

~

I looked for Sounds of the Desert. What Mom said was her favorite. She never showed it to me, as she had planned. The task got lost in others, and then in her sudden and rapid decline.

Sometimes Mom would write the names and years on the backs of her paintings. Sometimes she wouldn’t. So after she died, I went looking, I checked the backs of every canvas, and found Sounds of the Desert written nowhere.

So I looked for clues. For style. For a feeling. She’d said it was in the style of the painting now in Torun. Said there were horizontal elements, and white. She referred to the work in singular form, but then at another point said “these paintings.” She seemed to indicate it was upstairs, in the other room where I found her other paintings — the smaller canvases — and cutouts.

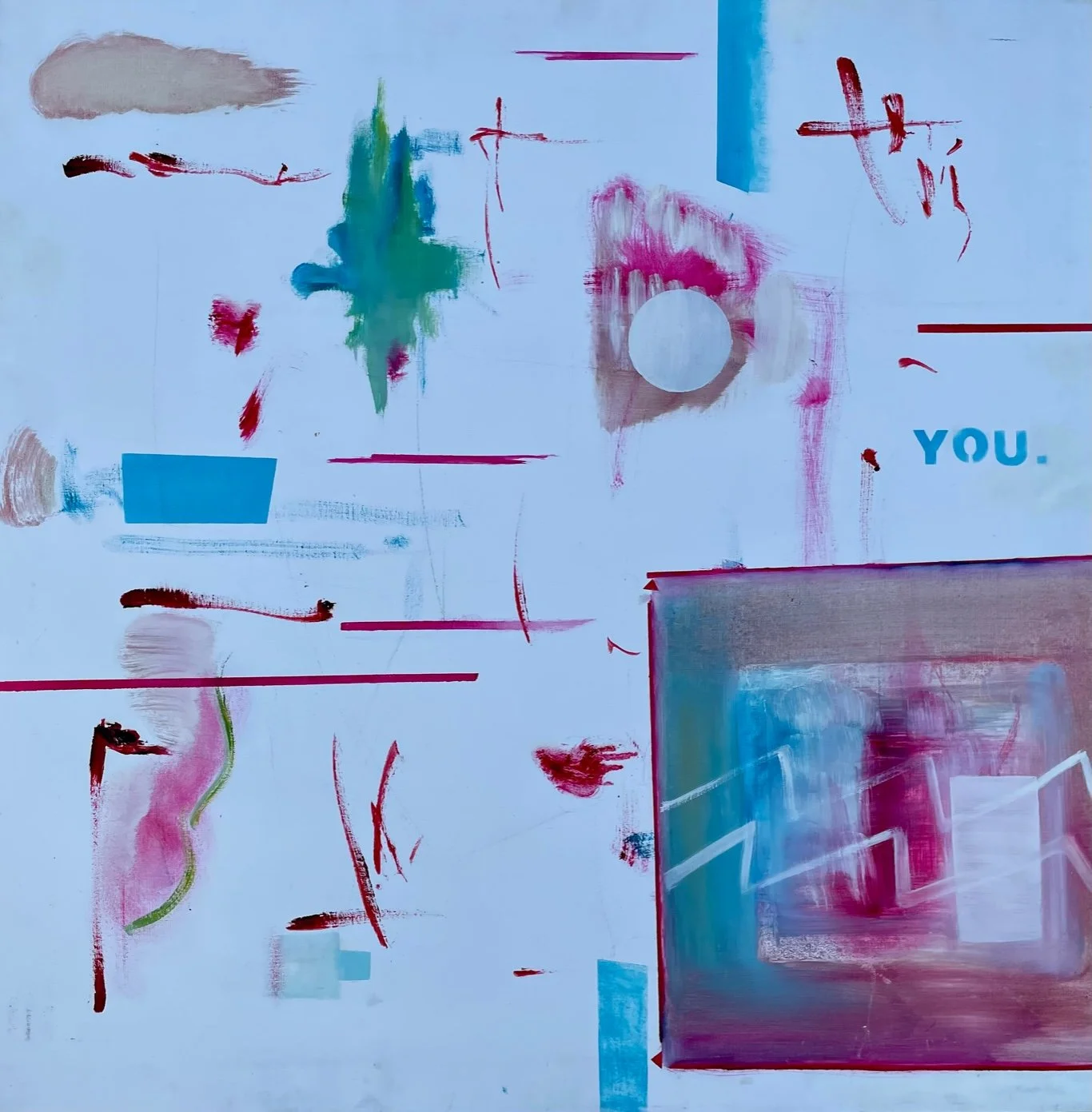

So I came to this one, 32x32, unmarked on the back, and thought maybe…

But later found a photo of this elsewhere, with the title also marked: You.

I thought maybe it could be this one, a smaller 16x20, and exactly as she had said, had imagined: cutouts, forms, lines floating…

I also considered these.

And then I came to these. A pair, on linen not canvas. Not white, but still light, and breathing. And I thought maybe. Maybe these.

Maybe also it’s better not to know.

Maybe the point is the looking.

~

As for what she thought was her end painting, the gray one, on the back of that canvas I found Peaceful Moment I, Anna Gajewska, 2009, written there. So the book she prepared for galleries, originally called War and Peace in my Heart, either it was written later than 2006, or she just folded this painting in to her story later, once she had painted it.

No matter. Mom’s story can be a constantly moving collage also, the dates, fragments and shapes rearranged this way or that. Plus, I found Peaceful Moment I written also on the back of another work, as well as a Peaceful Moment II — sister acrylics — from 2008, a year before the gray.

~

As for our story, our composition here — this arrangement of her fragments mixed with my lines, this project of ours which began as a question that still remains: what to do with a mess? Well, this needs an ending also. And we contemplated this together.

Together, Mom and I decided that this project, our writings and experience here, should be called, after all, Jazz. (Fuck Art, Let’s Dance was a close second.) And when I suggested that we could end it with just her words, her last statement there about wanting to paint free lines mixed with cutouts — but that we could add just the two more words at the end, as a final button, I wish — she liked this idea. “And you know what we could even put then, after that?” I added. “Your painting. This one—”

I went to fetch it. It was a painting I passed each time I entered or exited her bedroom with medicine, with her food, with Fillow, with the laundry or some bubbly. A painting she had just leaning there against the wall at the top of the stairs.

I held it in front of her.

She smiled, said she liked this idea too. Maybe she was being honest, or maybe she was just a mom encouraging her son, like always. Like when she told me at the beginning of all this — listen, you write whatever you want, and I’m sure it will be great, but said also that she would remain in the background, hands off.

But Mom was an artist, and thus a thinker, and clearly then she began to think about this composition — as our days pressed on, and as my words pressed to paper. I would read these little stories to her. And she began to look forward to these readings. Would laugh, would cry. She would tell me they were diamonds, and then the stones would crack open into other talks, other shapes.

And then, just on one or two occasions, she would suggest a tweak.

And one day, as I climbed the stairs up to her room, and again passed that question there in pink — Where do I we go from here? — I found her in bed as usual, but writing. And I smiled. And she ripped a page out from what she was writing in — a 2006 calendar, of course — and she said this, this is how we should end.

This was just before the decline. Just before she lost the rest of her energy, her words, her breath.

I took the page from her hand.

The Title of book: “Jazz”

No “I wish” at the end. Do not put Time Limit on Eternity. Anything can be done, accomplished and finished in Eternity.

We all have these strange bugs of …

… creativity in us and they will still flicker stubbornly trying to express something, trying to say something, and they will be able to do this — now not limited by time. Sounds like never before.