‘Some part of it survived’

There once was a field of art called literature. In those days, there were special stores selling items that we called books. The book consisted of several hundred pages, stapled and bound with covers. Inside there were black letters forming words, and the words formed sentences. These books contained novels, poems, essays or memoirs. They were read in bed, in an armchair, at a table, on a park bench or during travel.

The novel was a series of adventures, often complex and dramatic, of some individual who was called the novel's hero. The poems simply resembled the song lyrics of today’s youth bands. And the essays or memoirs were generally similar to contemporary talk shows, only of course more boring.

An interesting fact to note is that these novels, poems and essays were read alone and only with the book, without sound or visual effects, in complete silence and without the possibility of interference from a message of communication.

At the beginning of the 21st century, as a result of a quiet revolution, an era of hard drives began. The rapid development of electronic technology led to the rapid decline of traditional literature, which today can be found in specialized clubs of lovers of old art, of which, surprisingly, there are more and more of.

*

I have been toiling in or mulling over this literature, which everyone predicts will soon come to an end, for fifty years. I started when it was still sturdy and seemed to have a lot to say about the terrible past that had just passed and the promising future. I was either a product of literature or a bastard of it. For my generation, literature was a drug and stimulant. These printed pages pushed us into the slaughter of war and encouraged us to try to rationally make sense of an eternally limping world. I'm ashamed to say — that's how it was. Such was the astonishing, despotic influence that those humble black letters on fragile white paper had on us.

*

Three-fourths of those societies could not read and write. And those who knew how were afraid to write. Writing was witchcraft, some mysterious liturgy, and maybe even a form of sacrilege.

On street corners were offices where for a few dozen cents an expert could write for us an application to an official, a letter to a fiancée, or an anonymous denunciation of a neighbor.

But before literature died out, it underwent rapid democratization within the crucial second half of the 20th century. So before it died, it infected all groups and social classes. Suddenly, within a decade or two, everyone had written hundreds of thousands of novels, millions of memoirs, and billions of poems. People described everything they saw, remembered and imagined. They described all possible crimes and offenses, perversions and deviations, mental disturbances and incest, the decline of human nature and the imbecility that sprouts in our genes. They dethroned the gods of all religions and fell to their knees before a new god — the god of chaos. They blew up the entire edifice of their species’ achievements and pissed into space. They described the simple procedure of copulation in millions of volumes and in trillions of paragraphs they exposed the previously hidden reproductive organs. And then there was nothing to write about and literature gave up its ghost.

Wait a minute, that's not entirely true. Some part of it survived. It has become the common food of wild, primitive peoples inhabiting the spooky spaces of gigantic metropolises. Feeding on the scraps of this literature are tribes of secretaries, housewives, hordes of doormen or gas station attendants, packs of truant lower-class students, and gangs of abstract painters.

~

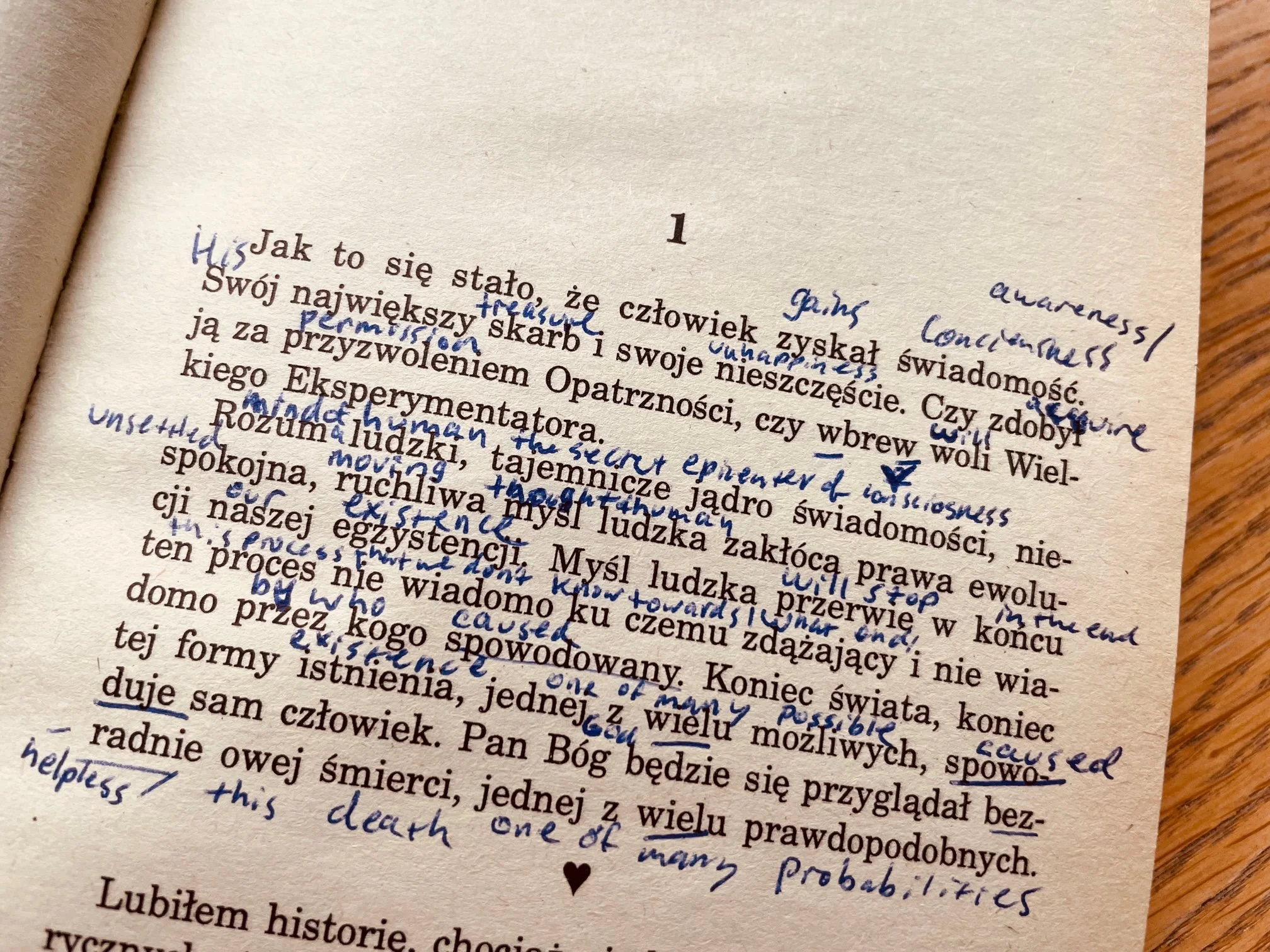

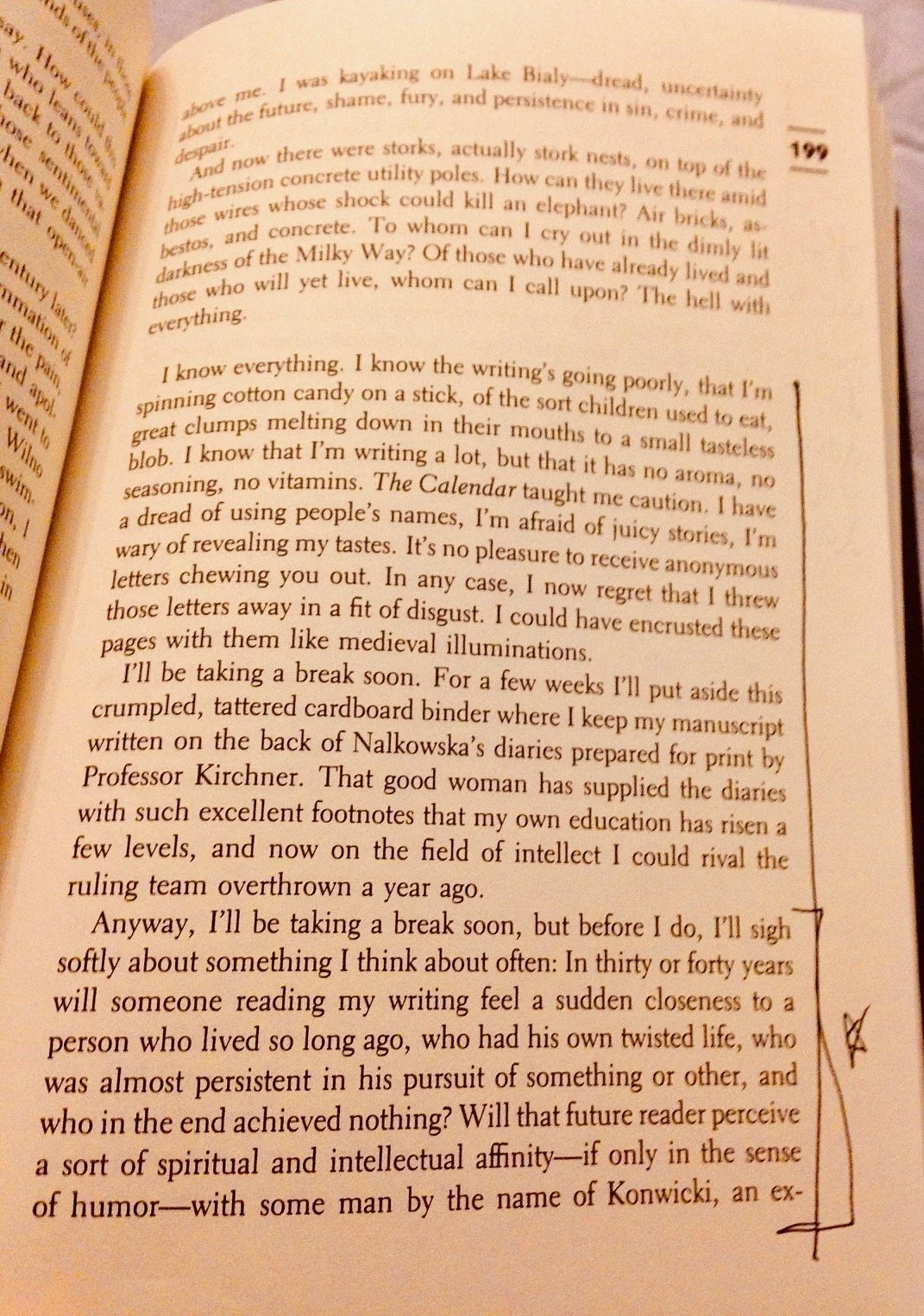

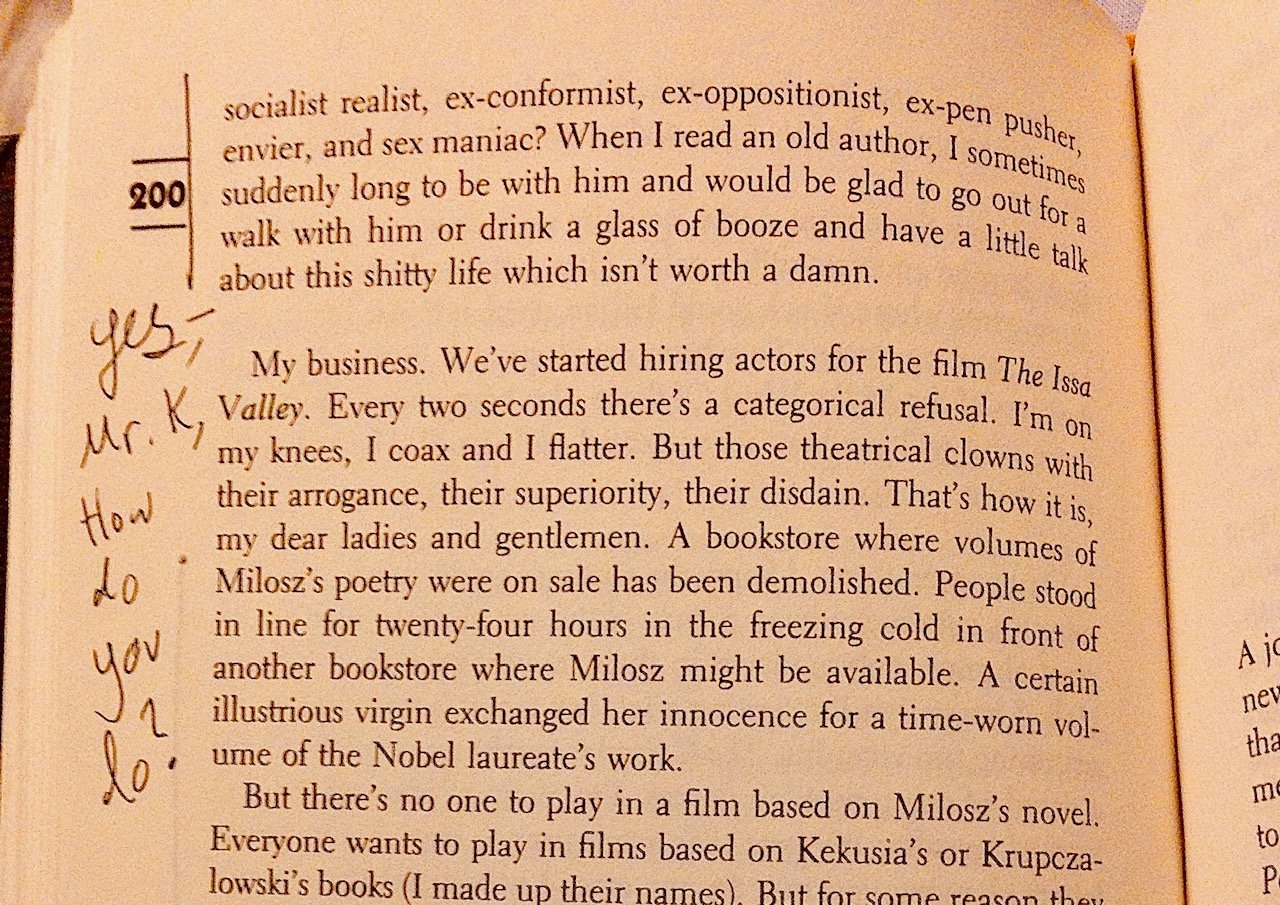

Today, I think of my friend Tadeusz Konwicki. He was not actually my friend, but this is how we think of our heroes. The excerpt above is my surely imperfect translation of his Polish, from the last book he wrote, never translated, called Pamflet Na Siebie, or Pamphlet on Myself.

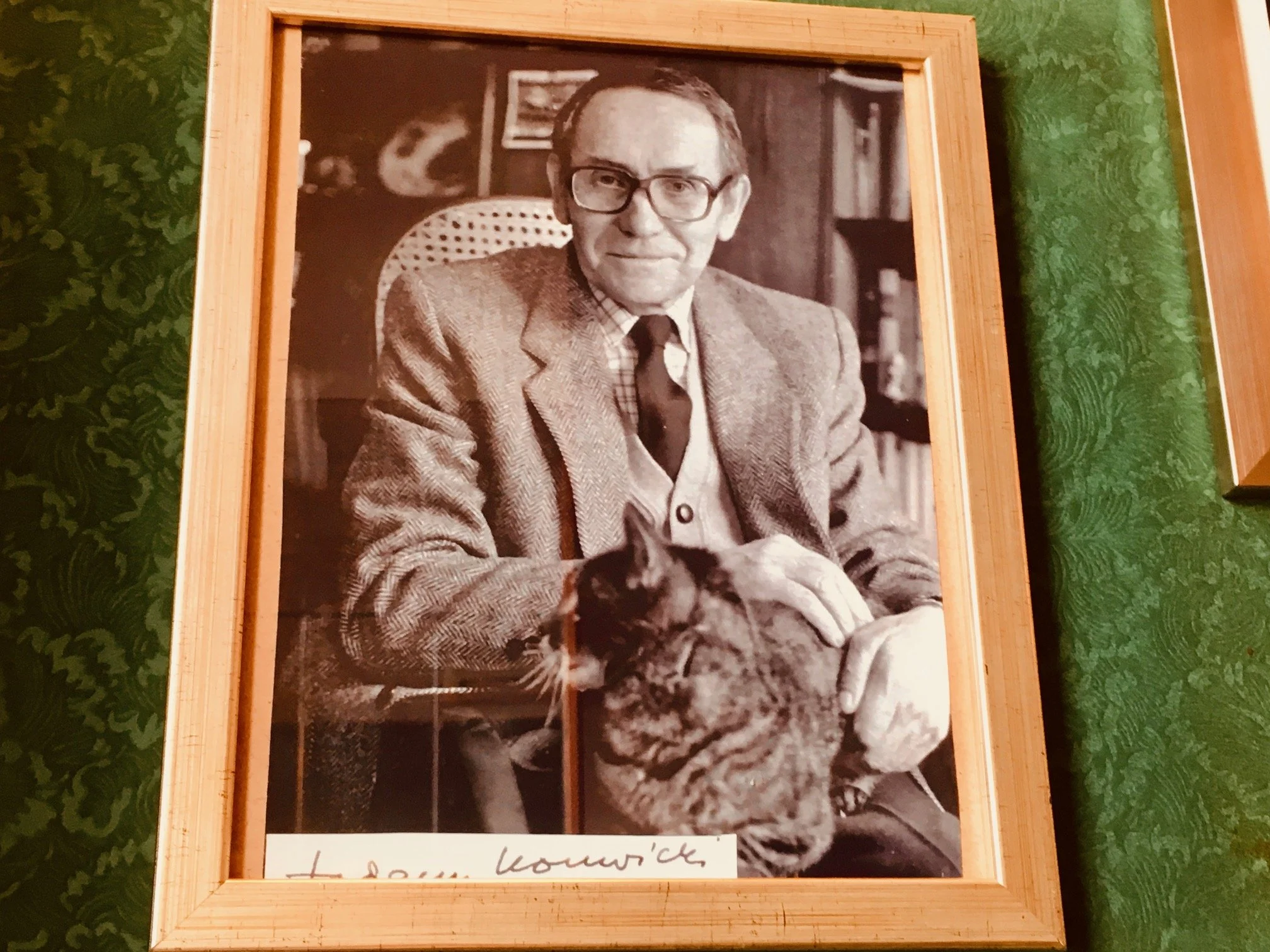

Tadeusz Konwicki was born on the 22nd of June, 1926, just outside of Vilnius, in what was then the Polish Republic, and later Russia, and now Lithuania. As a boy he learned to read and would lose himself in the books he acquired and took with him into the woods or to the banks of the Vilnia River. As an adult he became an author, writing often of the city he then lived in along the banks of the Vistula. He died there, at his Warsaw home, on this day, January 7, 2015.

So I think of him. I think of those magical weeks spent with him before he died — first with his literature, found by accident or providence while on a trip to his city; and then when I had the honor of shaking his hand.

Time keeps on slipping. I can’t believe it’s been this long. Yet still I can vividly feel that hand — his within mine, or then on my shoulder as he kindly offered it. I think of this and smile. And I’m so thankful for it, for him, for having ever crossed his path.

Excerpts from Pamflet na Siebie and Moonrise, Moonset (pictured), by Tadeusz Konwicki. / Photos by Jan Gajewski.