The edge of what’s around

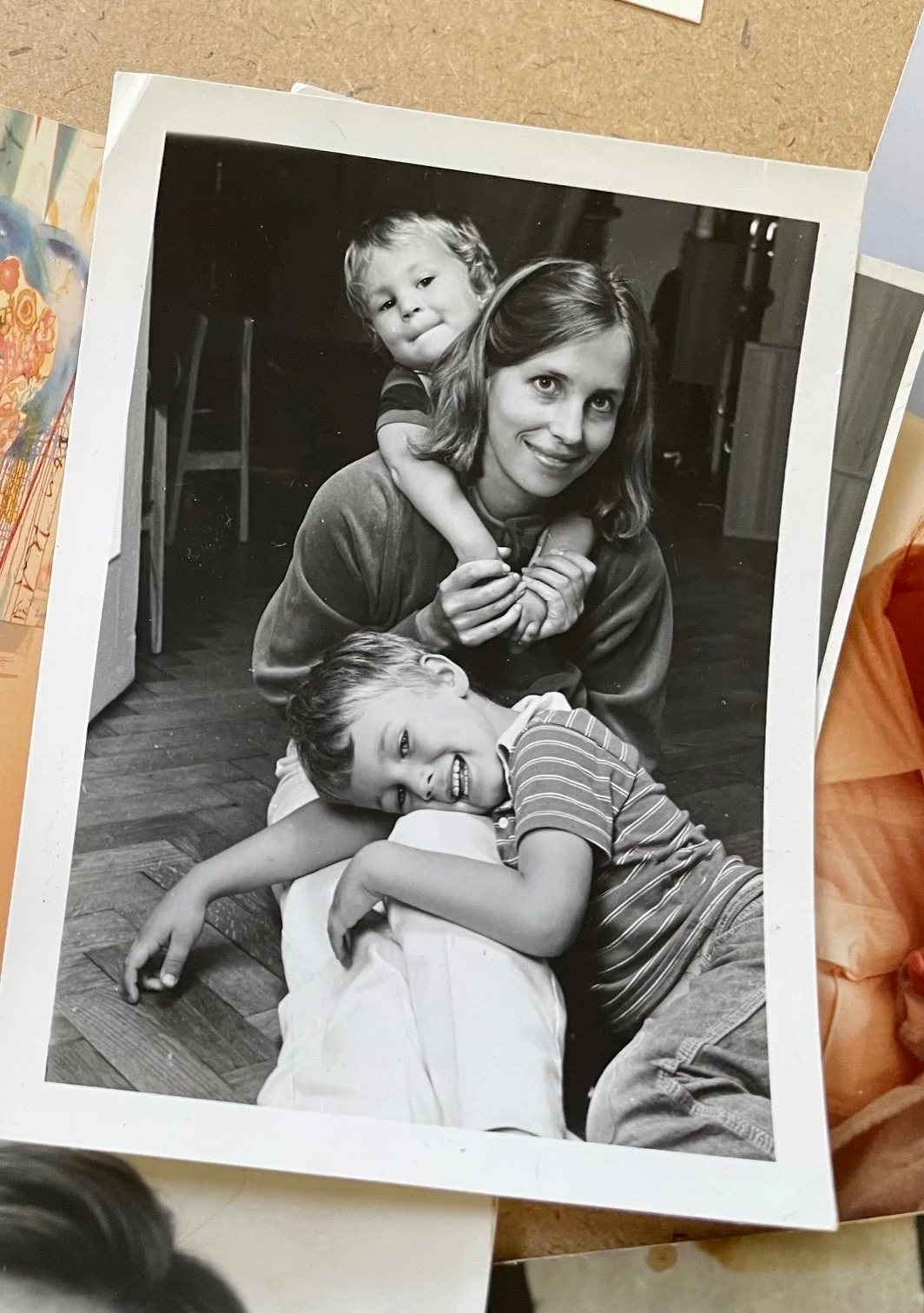

I remember shaving away my beard, in the small chance she would open her eyes again. If I was the last thing she ever saw, then I wanted it to be me.

I remember lying with her there, hugging her there, talking to her.

And the cats acting strangely.

And my brother arriving and seeing her, and crying, and praying.

I remember talking to her some more. Hugging her some more.

While I could.

I remember worrying if she was in any pain, it’s the one thing she’d been afraid of, and giving her the morphine how the nurse said I still could, through her lips and onto her gums.

Her lips, her gums.

That little bottle and syringe, and the thin clear wire carrying oxygen, and adjusting the wire all the time around her ears and face to keep those little nubs at her nose.

Her nose, her ears. Her hair, her face.

Her shallow breaths.

What remained of her there.

*

Today is her birthday.

We spend half our lives trying to remember the birthdays. Remembering to call, to write. To buy the proper things, go to the proper places.

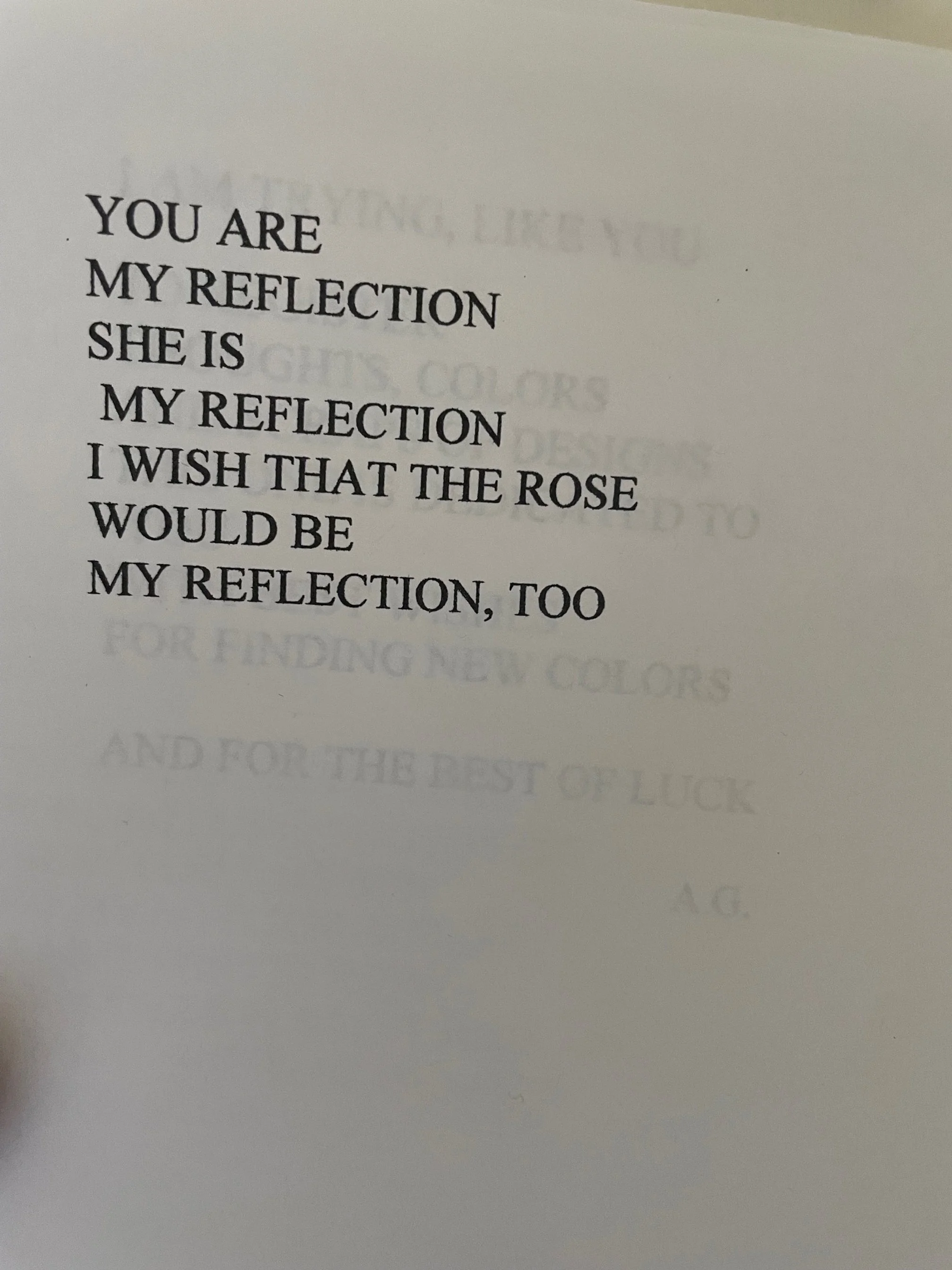

Half our lives we look for the right card, and the right words to put there inside of those narrow spaces.

The right flowers.

This time last year I remember her calling me and thanking me for the flowers. Telling me how beautiful, how wonderful.

I remember us trying also not to talk about It — the It inside, and what to do with It next; we’d been arguing about It but made a kind of pact: not on that day. On that day we wouldn’t argue. We would sort of pretend. And enjoy the smells and sights. Enjoy taste. Enjoy life — because chemo had spoiled these things for her but she was starting to find them again, which was why she wasn’t wanting to do the chemo anymore, or at least not for awhile, and that’s why we’d been arguing (me, I realize now, selfishly).

I remember how I called her Mama Bear — I remember because I never called her Mama Bear, but for some reason I did that day. Maybe to lighten. And I remember telling her I loved her. And wondering if it would be her last birthday, and wondering if she was wondering this also.

*

Half our lives trying to remember the birthdays. Then the other half maybe doing this. Remembering the birthdays and also now the dying days.

*

*

She’s at the edge of this, of me, all the time still. Even the word Mom lives at the edge of my lips and thinking. I’ll say the word in my head or out loud. I’ll say I miss you, Mom.

Months have passed and still she’s just there. At this edge.

I’ll see a thing that’s beautiful and still my first thought is not that it’s beautiful, but that she would think it beautiful.

I’ll see a good movie and think how she would have liked it, would have laughed there, and cried there.

I see spring — another spring now here, the new colors, new leaves, new life — and I see her in the colors and in the leaves. And I see her doing just exactly what she would be doing: walking up to the leaves and any flower there, and pulling it close, and inhaling.

No one inhaled life so deeply as my mother. So when I see life blooming, well of course I see her there in the flower. Or beside it. I only wish it were really her. And it is, but it isn’t. And the silence and the void and the edge of this hurts. The stillness of it still hurts.

*

*

Today we were going to visit her, take flowers to her. We were going to do these same things, only at the cemetery now, because that’s what we do once the dying days have come: still we buy the flowers, make the visits. Still we try to talk to the person there, try to find the words to fill in the narrow spaces, only now we do this for ourselves.

But we didn’t end up going.

Maybe tomorrow. Maybe in a few more days when the weather is warmer. Because as it happened the doctor we’d been waiting to see for Babcia’s pain, for the awful sciatica my grandmother’s been having — my mother’s mother — well the doctor we’d been waiting for could only see us today. So we went there instead to the other side of the city, the other side of the river. And somehow this was better. This was right. This was just exactly what she would have been wanting us to do — something for her, not me. Something for the living. For pain still there.

“Don’t worry about me, I’m not going anywhere.”

I hear her saying it really.

*

Now evening, the day itself now dying.

My grandmother received the injection she badly needed.

And we’ve eaten. We’ve talked. We even managed a little walk.

Dying days, and the pain of living.

And this is about when she would have called, called or written. Her, and then me. When she would have wanted to hear our voices, wanted to hear about it all, wanted to check if we’re OK. And wanting to tell us, again, not to worry about her. Really, she was doing fine.

*

She never opened her eyes, never saw me again. Not that I could tell.

I don’t know if she could still hear or feel me.

Or about the pain.

But still we hear and feel her. See her. Still we talk to her, and try to hold on.

And still we say it.

We miss you. And Happy Birthday, Mom.